views

Improving Your Argumentative Skills

Lead with evidence and avoid emotion. The most effective way to win arguments is to build evidence-based cases using logic. This shows that you’re well-informed, prepared, and impartial. If you make emotional arguments that are about what you believe or feel, your opponent will quickly be able to come out on top. If your argument is full of “I” statements, your opponent may ask why people should trust your opinion. To avoid having to defend yourself in this way, keep the argument from being about you. This doesn’t mean you need to completely avoid examples or evidence that could cause other people to become emotional. For example, you might want to tell a story about a child affected by toxic drinking water if you’re arguing for better water pipes in your city. Pair this moral example with statistics, historical examples, and other evidence.

Be logical, clear, and simple when communicating your argument. Use language that your opponent and anyone who’s listening will understand. Avoid including unnecessarily big words and complex concepts in your argument. Present a step-by-step case that doesn’t leave anyone tilting their head in confusion when you’re finished. For an example of an argument that uses complex language: “Implementing universal online voter registration and voting might, all things being equal, stimulate voter interest, ameliorate the current bureaucratic morass, and revitalize American democratic processes.” The same argument presented in simpler terms: “Allowing Americans to register and vote online would make voting easier. This would hopefully encourage more people to vote. It would also cut down on unnecessary paperwork.” To decide whether you’re using concepts or language that’s too complex, ask yourself whether a 10-year-old could understand your argument. If the answer is yes, then your audience will follow your logic, as well.

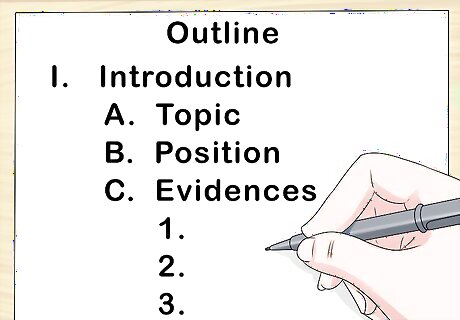

Plan out your argument ahead of time and write an outline. This is the best way to make a logical, step-by-step case. Structure your argument like an essay. First, introduce your topic and position, then present at least 3 pieces of evidence. Allow your opponent to respond. Finally, conclude by disputing (or rebutting) their points. Even if you can’t make a written outline of your argument ahead of time, you can still take a minute to organize your case. Silently plan in your head for a minute or so, then begin arguing.

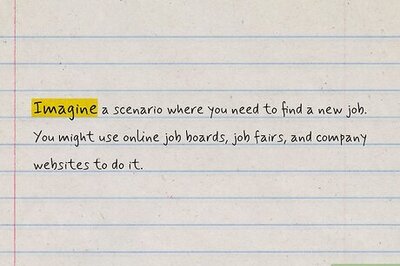

Take the time to understand your opponent’s argument. These kind of arguments are what are known as “two-sided arguments,” and they’re much more effective than “one-sided arguments.” If you’re able to see both sides of a topic, you’ll be better prepared. You’ll also have better and more concrete reasons for choosing your side, since you’ll have explored the different options. Before you come to a decision about a particular issue, look up arguments from both sides. Stay informed by reading the news each day and looking up sources from multiple news outlets.

Use counter-arguments to undermine your opponent’s argument. Counter-arguments respond directly to points made by your opponent. This is the most effective way to decisively win arguments. Counter-arguments (or rebuttals) are most powerful when they identify specific details in your opponent’s case that don’t make logical sense. To keep your debate ethical and fair from start to finish, don’t make emotional or personal counter-arguments. If your opponent says something like, “Half the country experienced colder winters last year! Climate change isn’t real.” You could counter with: “Climate change doesn’t mean that cold weather won’t happen anymore. Right now, the world is experiencing a general warming, which could actually cause more variation in weather patterns from year to year.” Don’t respond with a counter like: “How can you assume that just because it’s snowing in Indiana, climate change isn’t real?” This argument attacks your opponent’s intelligence and doesn’t advance your case.

Identify illogical reasoning in your opponent’s argument. Point out illogical points during your rebuttal. To make note of them, listen carefully when your opponent makes their case. Notice when they say they’re arguing for one thing, but it’s clear that their position actually supports something different. Evaluate the credibility of their sources. Also look for: A post hoc fallacy. This is when someone misattributed effects to particular causes. For example, if you’re debating the value of social welfare programs, your opponent could say something like: “When Congress cut welfare spending, unemployment went down and more people got jobs. Welfare spending therefore causes people not to look for jobs.” Since there are lots of reasons (not just one) why unemployment could go up or down at any given time, this argument isn’t logical. A non sequitur. This happens when someone makes a conclusion that’s related to a certain premise, but the premise doesn’t actually support the conclusion. For example, if you’re debating school lunch menus, your opponent might say: “children really like pizza. Therefore, pizza should be the main lunch food served in public schools.” This is an illogical argument because while it’s true that most children enjoy pizza, it’s not the healthiest lunch food option. Generalizations based on stereotyping are also common illogical arguments. Be wary if your opponent makes a statement about a whole group of people (“all women,” “poor people,” “inner-city youth”).

Being Prepared with Evidence

Visit the library or go online to do research. Start by doing a basic Google search on the topic you’re arguing about. This should give you some background information. Then search for books about your topic and head to your local or school library to check them out. The librarian can also help you gather even more information both online and in the stacks. For example, if you’re arguing about climate change, start by Googling simply “climate change.” You can then do more in-depth online searches by typing phrases like: “debates over climate change” or “scientific studies on climate change.”

Choose credible sources when you do research. It’s sometimes difficult to know which sources you can trust. It’s generally a good idea to rely on more recent sources (say, published within the last 5-10 years). You can also look up authors to find their experience and credentials. Ask your librarian for help, as well. They’re trained to find the best possible resources out there. When doing online research, this is even harder! Look for .gov, .edu, and .org sites. Even with these sites, double-check your information and look up authors. Be especially wary of online sites that have spelling or grammar mistakes.

Use statistics when you can explain why the numbers matter. Citing statistics in an argument can be a great way to provide detail-oriented evidence. Statistics also usually provide measurements of results over time. So if you’re arguing about a change in governmental policy, for example, statistics could be the perfect evidence to help you win your argument. If you’re trying to argue for the effectiveness of gun control laws, for example, you might look up worldwide statistics about gun-related deaths before and after gun control legislation was passed. When you’re looking up statistical studies, make sure the study was conducted impartially and effectively. Generally, university and government studies are more reliable than those produced by private organizations. Find out if an organization paid for a statistical study (even if it’s a government or university study) before you cite it! Private funding could cause the results to be biased. Statistics can be manipulated in the hands of savvy or tricky opponents. If your opponent cites statistics, listen very carefully for the sponsors of the study they’re referring to, the date and length of the study, the accuracy of their numbers, and the relationship of the stats to your argument.

Rely on historical examples to put your argument in context. Anecdotal (or narrative) evidence from history can help you explain how your argument relates to what happened in years past. This evidence is useful if you want to show how the world got to where it is today, and if that means that things need to change or stay the same. For example, if you’re arguing about civil rights protections for LGBTQ folks, you might want to provide some historical background on civil rights struggles and advances for other groups of people around the world. Find out which laws were passed when, why they were passed, and if they’ve made a difference in expanding civil rights. To look up historical examples, start with credible sources online and then look for more details in book-length studies at the library.

Cite experts’ opinions and explain how they reached their conclusions. While you can and should cite experts’ opinions in your argument, be prepared for your opponent to challenge that evidence as an interpretation rather than a fact. To use this kind of evidence effectively, explain how the expert reached their conclusion. Take your opponent through their study and provide key details showing why the study is convincing. In debate, a “fact” is considered something that’s indisputable, like 2+2=4. Choose experts who have spent years studying and doing research on the topic you’re arguing about. It’s best if their work isn’t privately funded.

Research all sides of a topic to prepare for counter-arguments. Get familiar with all of the available information on a particular subject instead of just sticking to the stuff you agree with. This way, when your opponent brings up a specific case study or example, you’ll be prepared to discuss it and dispute its conclusions. Examine all of your sources critically by asking yourself the following questions as you read: When was this source written or produced? What was happening in the world at that time that could have affected the author and their interpretation(s)? What’s the major implication of the study’s conclusion(s)? Is that implication controversial? What kind of language does the source use? Is it exaggerated or biased? Is there an obvious part of the story that the source has left out?

Arguing without Getting Emotional

Respect your opponent’s position. Just because you don’t agree with your opponent doesn’t mean you can’t try to understand why they’re defending this particular position. Empathize with your opponent by putting yourself in their shoes. This will help you form a reasoned argument that accounts for both sides of the issue. It’ll also help you avoid attacking your opponent. Ask yourself why your opponent is passionate about this topic. What values or belief systems could be motivating them to argue against your point? Did something happen to them in their past that solidified their viewpoint? Even if you don’t agree with those motivations, you can respect them.

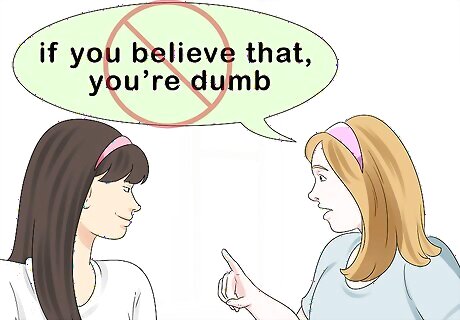

Avoid making personal attacks in your argument. Statements like “if you believe that, you’re dumb” directed at your opponent won’t help you win your argument. You also shouldn’t make personal attacks on experts or other people that your opponent relies on to make their argument. These attacks are emotionally driven opinions, not fact-based reasons. For example, you wouldn’t want to say something like “that scientist is a horrible person! Why would you use him as your expert witness?”

Argue to show why your argument makes sense, not to win. When you set out only to win, you’re putting limits on what the debate can be. Any argument can be a learning experience for both participants. If you enter the argument hoping to demonstrate the superiority of your argument instead of seeking to tear your opponent down, you’ll be better for it. Arguing to win and arguing to prove you’ve got the better case are subtly different! When you’re focused on the strength of your position instead of winning or losing, you’ll act more like a teacher giving a reasoned lecture than a general fighting a war. A win-lose mindset will also be more likely to inspire strong emotions like anger, resentment, or frustration.

Search for common ground when things heat up. There’s almost always some point of agreement between 2 sides. To diffuse emotion and bring logical reasoning back into an argument, find that agreement. You can then tell your opponent that you agree with them on some points, but that you differ on others. This should act like a “reset button,” and you can then continue arguing with renewed courtesy.

Take deep breaths when you begin to feel angry. Put the argument on pause for a moment by breathing in through your nose and slowly letting it out through your mouth. Use this break to recenter yourself. Imagine your anger flowing out of your body along with your breath. As you breathe in, silently remind yourself that this isn’t personal. You’re arguing to show the merits of your case, not to tear someone down or hurt them.

Know when to walk away from an argument. Sometimes, it’s impossible to have a logical argument with someone. Unproductive arguments that become emotional and personal don’t help anyone, because neither side will end up learning from the other. If your opponent won’t stop attacking you or your values (or if you can’t prevent yourself from doing the same to them), put an end to the conversation. Arguments where people are shouting or screaming at each other also aren’t useful. Don't reply with an immediate, knee-jerk reaction. It's okay to get back to the person later.

Comments

0 comment