views

Determining Your Readiness

Know the full costs of living on your own. Maybe you make $750 a month, have heard that little studio apartments can be had for $500 a month in your area, and have already started planning parties for your new bachelor pad. But hold up before packing up. Rent is only part of the cost of living on your own. Don’t forget about utilities, food, supplies, laundry, property insurance, and so on — all those things your parents probably take care of at home. Adding 30% to your rent is one way to roughly determine your actual housing cost (utilities and renter’s insurance). So, that $500 studio actually costs you at least $650 per month, without factoring in food, toilet paper, or transportation, among other costs. Ask an older sibling or friend who lives on their own how much it actually costs. Arm yourself with accurate information so you can realistically determine whether you can afford to set out on your own at this time.

Create a personal budget. You’re ready to be (and be treated like) an adult, and want your own place like one. Prove it by getting serious about your finances. Making a budget may not be the most exciting task, but it is a simple and important one. It really is as easy as recording your monthly income and expenditures. Do this for at least a few months to get an accurate picture of your monthly budget. There are numerous website calculators and apps available to help you with household budgeting and tracking spending. But a pen and paper can work just fine as well. Be thorough in tracking your expenditures. Don’t forget about your morning coffee runs, your video streaming service account, or your bus pass / car insurance. The more accurate your calculations, the better equipped you’ll be to determine your readiness to move out.

Practice while still at home. While it’s hard to pass up letting your parents foot the bill for your major living expenses while at home, it may be better for you to get into the habit of planning for and actually paying for such necessities. Pay rent. Your parents may balk at this notion, but it is one way to demonstrate to them — and yourself — that you are an adult who can take on adult responsibilities. The amount doesn’t necessarily have to be the fair market rate for your area; the actual process of paying rent on time and in full is a good habit to form before setting out on your own. If paying rent really is a non-starter with your folks, insist upon paying for your share of the utilities, for instance. It may be best to make yourself responsible for one monthly utility payment (the water bill, perhaps) to establish good bill-paying habits. This article is about saving money for moving out, so spending money when you don’t have to may seem counterintuitive. But, if you move out before you are prepared for the realities of living on your own, including paying bills, the cost to your wallet (and pride) will likely be much greater than some little monthly rent check with your parents.

Pay off your debts, or at least pay them down. You may be eager to get out of the house and start living your adult life your own way, but waiting until you can put yourself in a manageable debt situation will almost certainly put you in a better position both short- and long-term. If you are a recent college graduate, the odds are good that you have some — or maybe a lot — of student loan debt. Unless you’re willing to stay at home until you’re 40, it may not be possible to eliminate this debt before moving out. However, every little bit you can pay down before the increased expenses of independent living take hold, the better off you will be. Credit card debt may be a more realistic option for elimination before moving out. Think of it as a form of saving for moving out, because eliminating this ever-increasing burden will offer you more financial freedom when you do move out.

Build up a good credit profile. If you have a poor or non-existing credit rating, you will probably find it difficult to find a reputable landlord that will rent you an apartment. Establishing good credit is beneficial for many aspects of the transition to adult independence. Paying down existing debts is critical to improving your credit rating. While this helps erase negative factors, there are also ways to enhance the positives of your creditworthiness. Open one or more credit cards and pay them off in full monthly. Use the card(s) regularly to buy items you know you can afford (gas, not a flat-screen TV) and pay off the bill on time. Staying well below your credit limit each month is also a positive for your credit profile. Holding a steady job and an established bank account are also beneficial to your credit profile. So is a steady primary residence, but we're working on that part here! For more ideas, consult How to Build Good Credit. If you have to rent a house with bad credit, you can do it by finding good rental opportunities and improving your rental application.

Saving for the Move

Establish your minimum savings goal and maximum rent payment. One of the most obvious ways to determine your financial readiness to move out is to know how much money you’ll need and how much you can afford to spend. However, some people ignore this crucial step amidst their excitement at the prospect of moving out. There are numerous formulas for determining the maximum rent you can afford floating around the internet, but two simple options are to divide your monthly gross income by three or your yearly gross income by forty. (Gross income is your pay before taxes are taken out.) Thus, if you make $2400 per month, you can afford an $800 monthly rent. Or, if you make $20,000 per year, you can afford $500 per month. There is greater variance in advice on how much you need to save before moving, depending upon prevailing rents and many other factors. One formula, which factors in greater rent costs for greater salaries, along with moving costs, basic supplies, etc., advises that someone making $20,000 per year needs to save up $1750; $30,000 per year requires $2250; and someone making $40,000 per year should have $3400 saved.

Make a habit of saving. Every financial advisor worth their salt will tell you to start saving now, even if it’s just a little bit per paycheck, because it establishes good habits and (literally) pays greater dividends in the long term. Having a clear goal, like knowing that you need $2500 saved up before moving out, can make saving easier, but there are numerous strategies that can help. Many of these, such as having funds taken directly from your paycheck to savings (just like taxes), can be found at How to Save Money. Practice saving not just for the move, but to establish an emergency fund once you do move. One common recommendation is having an emergency fund that can cover three to six months of your expenses (use your budget as your guide). EXPERT TIP Priya Malani Priya Malani Financial Advisor & Founding Partner, Stash Wealth Priya Malani is a Financial Advisor and the Founding Partner of Stash Wealth, a financial planning and investment management firm for HENRYs™ (High Earners, Not Rich Yet). She has over 15 years of wealth management and financial advising experience. Priya's work with Stash Wealth has been featured in Fortune, Wall Street Journal, and CNBC as well as entertainment and lifestyle brands such as the NYPost, Bustle, SiriusXM, and Refinery29. She earned a BA in Economics from Agnes Scott College in 2004. Priya Malani Priya Malani Financial Advisor & Founding Partner, Stash Wealth Expert Trick: Put money into savings before you spend anything after getting paid. If you have a savings account at a bank, you can check to see if it's possible to automatically deduct money from paychecks to go directly into savings every month.

Tighten your budget belt. Once you’ve established your monthly budget and the amount you need to save in order to move out, look for ways to trim the fat from your expenditures. Divide your budget into essentials, which might be groceries, utilities, or transportation costs; non-essentials, like dining out or the sports tier on the cable package; and extravagances, like designer clothes or concert tickets. Cut out extravagances, cut back on non-essentials, and see if any creative reductions can be made for essentials. How to Live Within Your Means offers many tips on cutting back on expenditures, including: shopping for items on sale or at second-hand stores; replacing memberships with free leisure and entertainment options, like jogging and a library card; and cutting back on impulse buys by making shopping lists and waiting at least 48 hours before making non-essential purchases. You may plan to cut back only temporarily in order to save up what you need to move out, but you might also find that at least some aspects of this leaner budget can become permanent fixtures, to your financial benefit.

Supplement your income temporarily. If you’re eager to move out, taking on a second (or third) job can help you save up funds faster. This can be beneficial in the short term, but don’t expect to be able to keep up an unsustainable work pace in order to keep your own place once you move out. That is, if you usually make about $30,000 per year but are able to temporarily boost up to a $40,000 per year pace by maxing out on overtime, don’t assume you can afford a $40,000 per year level apartment. Taking on overtime at your job is one way to boost income temporarily. Other options include: taking on odd jobs around your neighborhood, like lawn care, painting, or house- or baby-sitting; finding one-off sources of cash like holding an advertising sign at a busy intersection; using your musical talents by being a street performer; or doing additional jobs around your parents’ house for pay (don’t think of it as returning to getting an allowance, think of it as an investment in your future of independent living).

Sell your stuff. Now is the time to go through your clothes, your music and movie collections, your old dorm mini-fridge and hot plate, and whatever else might be worth a buck or two to someone else. The advantages of selling non-essentials are two-fold: you make some money for your moving out fund and you save some money (or at least time and energy) by reducing how much stuff you take with you when you do move. Have a yard sale, sell your stuff online, or take it to a secondhand store or consignment shop — use whatever means at your disposal to lighten your load and fatten your wallet. Be honest with yourself — will you ever listen to that CD or wear that flannel shirt again? If you can do without it, then do without it when you move out. Donate whatever won’t sell — you’ve already decided you don’t need it, and you can feel a little better about yourself for helping a worthy cause.

Saving with the Move

Be a savvy apartment hunter. Just because you’re eager to move out, don’t just sign off on the first place that catches your eye. Do some research, view several options, and consider details beyond just the rent payment. Use real estate listings to get a feel for prevailing rental rates in your area, and how they fluctuate based on details such as location. Focus only on prospective apartments that fit within the maximum rent you can afford; don’t give yourself the chance to fall for a place you can’t have. Weigh factors beyond just dollars and cents as well. For instance, if one apartment costs $50 more per month than another but is right on the bus line to work, it may be the superior choice.

Bring in an apartment-hunting veteran for assistance. Just because you don't want to live with Mom and Dad anymore doesn't mean you shouldn't take advantage of their experience with apartment / house hunting. A trusted friend or older sibling is also a good bet. Make it clear that the decision is ultimately yours, but rely on one or more extra sets of eyes to help identify sketchy landlords, rodent problems, potential noise problems, and so on. Your parents are almost certainly going to want to help, so this is a good way to help them feel involved and helpful.

Take only what you need. This relates to the previous advice regarding selling your non-essentials, but it is worth reiterating that taking a bare-bones approach to furnishing and stocking your first apartment is usually your best bet. Once you’ve sold / donated / discarded what you don’t need, think about what else you can do without, at least for the time being, and see if you can leave it behind at your parents' house. That way it can be accessible in the future or if your needs change, but not take up space (or moving expense) in your apartment. For items you need but don’t have — perhaps furniture, dishes, or bedding — visit thrift stores or yard sales, or just see if you have any family or friends looking to unload some stuff. Your first apartment doesn’t need to look like it belongs in a magazine. A beat-up couch and mismatched dinner plates will not ruin your first taste of independent living.

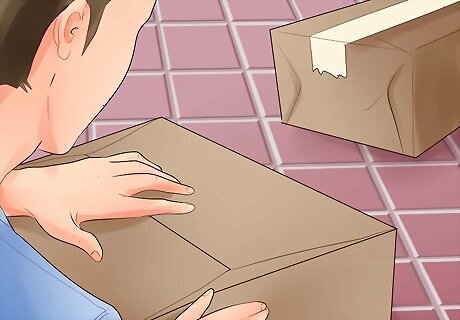

Utilize professional movers judiciously. It may be easier to let the pros load up all your things at your current place and carry them into your new digs, but it comes at a cost. Local movers typically charge $100 or more per hour, so a total cost of $300-$600 is not uncommon. Long-distance moves will cost even more. See if you can round up some family members or friends who are willing to work up a sweat for a few hours on a Saturday in return for some pizza and soda (or other beverage). Promise to return the favor someday. If you don’t have access to a pickup truck — or that just won’t do for your larger items — look into renting a truck and doing the moving yourself (with help). If the prospect of moving your couch, bed, and other heavy items is too daunting, let movers take care of that and move as much as possible yourself. Local movers typically charge by the hour, so the less they need to move, the less you pay.

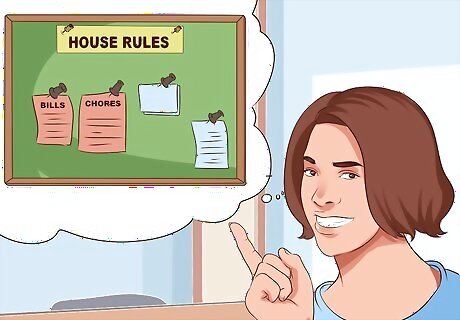

Round up some roommates. You may want to depart your parents’ house so you can have a place all your own, but sharing the cost with one or more roommates can make moving out more feasible. Whether you’re planning on sharing a place with an old friend or (hopefully) making a new one when moving into an occupied apartment, the prospect of splitting the rent, utilities, etc., by two, three, or even more ways can be quite appealing. However, even if your odds of a horror movie-worthy roommate situation are remote, establishing some clear ground rules is always wise. Be clear on things like how bill payments will be divided up, whether food will be bought communally or individually, and any responsibilities should someone decide to move out, to name some potential pitfalls. Even — or maybe especially — if rooming with an existing friend, be sure to spell out expectations and responsibilities so you don’t end up holding the bag for overdue rent and utility payments. You may want to draw up a roommate agreement on your own, which details the expectations and responsibilities of each flatmate. Also decide whether you want to have all the roommates' names on the lease and bills. If it's only your name on the lease agreement, you alone are legally responsible for unpaid debts. It is, however, easier to kick someone out if they're on the lease.

Comments

0 comment