views

X

Research source

A variety of teaching tools can help you work effectively with your child or your classroom and make learning addition fun.

Using Manipulatives

Use objects to demonstrate how addition works. Children respond well to visual tools that help them understand addition concepts. Any easily handled object may be used, from beads or blocks to Cheerios. Start with a small number of items and use a variety of tactics to demonstrate number relationships: Give the child two small groups of items -- say, a group of two blocks and a group of three blocks. Have the child count the number of blocks in each group. Have the child combine these two groups of objects and count the total number of blocks. Explain that they have "added" these groups together. Provide a set number of objects -- six Cheerios, for example -- and ask your child how many ways they can combine groups of Cheerios to make six. They might create one group of five Cheerios, for example, and one group of one. Demonstrate how you can "add" to a group of objects by stacking. Start with a stack of three pennies, for example, and add two more to the stack. Ask your child to count how many pennies are now in the stack.

Group children and use their bodies as human "manipulatives." In a classroom setting, take advantage of your young students' need to move around regularly by using them as human manipulatives. Utilize tactics similar to those you'd use with objects to group and combine students and have them count themselves in different configurations.

Consider having children create their own manipulatives. Use modeling clay to create manipulative objects, or combine your addition lesson with an art lesson in using scissors to create a collection of paper shapes. EXPERT TIP Joseph Meyer Joseph Meyer Math Teacher Joseph Meyer is a High School Math Teacher based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He is an educator at City Charter High School, where he has been teaching for over 7 years. Joseph is also the founder of Sandbox Math, an online learning community dedicated to helping students succeed in Algebra. His site is set apart by its focus on fostering genuine comprehension through step-by-step understanding (instead of just getting the correct final answer), enabling learners to identify and overcome misunderstandings and confidently take on any test they face. He received his MA in Physics from Case Western Reserve University and his BA in Physics from Baldwin Wallace University. Joseph Meyer Joseph Meyer Math Teacher Make learning math fun. Every kid learns differently. Build on your child's strengths with playful academic activities and games that use their existing skills. By understanding how your child sees numbers, you can unlock their potential and help them become stronger at math.

Employ game pieces in new ways to create addition games. Dice lend themselves easily to beginning addition games. Have students roll two dice and practice adding the resulting numbers. You may also use playing cards or dominoes. When working with groups of students with varying abilities you may tailor this game to provide an extra challenge for quick learners. Instruct them to add the results of three or more dice or playing cards.

Count with coins. Use money to practice adding ones, fives, tens, and even intervals of 25. This tactic teaches money skills in addition to addition, and has the added benefit of demonstrating the practical advantages of learning addition.

Introducing Math Language and "Fact Families"

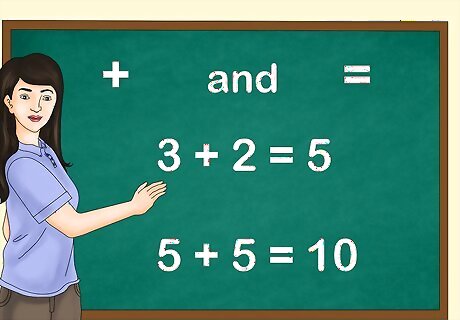

Familiarize children with addition symbols. Teach them the meaning of the symbols "+" and "=." Then help them learn to write simple "number sentences" -- i.e. "3 + 2 = 5." Begin with horizontal number sentences. Young children are already learning that they are supposed to write words and sentences "across" paper. Following a similar practice with number sentences will be less confusing. Once children have mastered this concept you may introduce the concept of vertical sums.

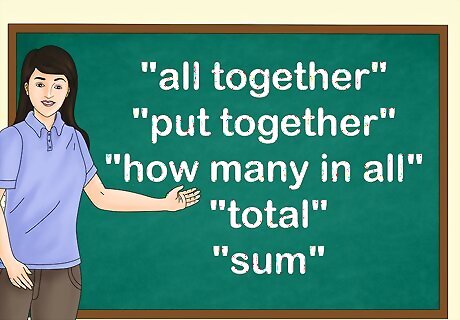

Teach children the words that signify "addition." Introduce terms such as "all together, "put together," "how many in all," "total," and "sum" that commonly indicate a child will need to add two or more numbers.

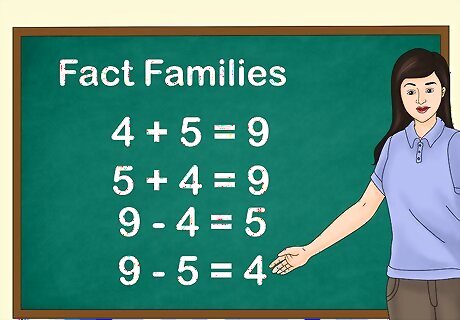

Use "fact families" to help children understand number relationships. Fact families show how the various numbers in an addition problem relate to each other. Fact families often incorporate both addition and subtraction to help students understand the inverse relationship between these two skills. The integers 4, 5, and 9, for example, are a "fact family," because 4 + 5 = 9; 5 + 4 = 9; 9 - 4 = 5; and 9 - 5 = 4. Consider using milk cartons to illustrate "fact families." Cover cartons with paper, or a wipe-clean surface if you'd like to re-use the cartons. Have students list the integers of a fact family on the top of the carton -- for example, 4, 5, and 9. Next, have them write one fact from these numbers' "fact family" on each of the carton's four sides.

Memorizing Basic Facts

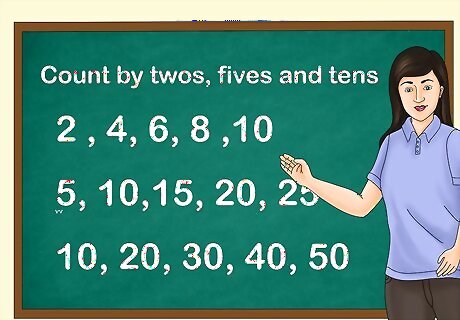

Instruct children in "skip counting." Learning to count by twos, fives, and tens to 100 will improve your child's understanding of number relationships and begin to provide easy reference points.

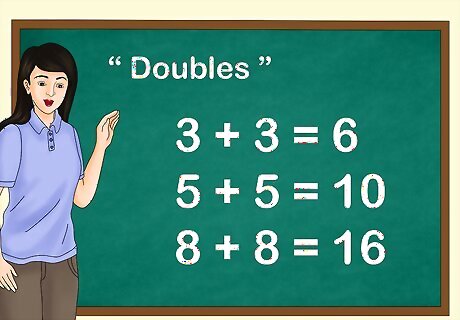

Encourage children to memorize "doubles." "Doubles" are math facts such as "3 + 3 = 6" or "8 + 8 = 16." Again, these facts provide easy reference points as students learn to add. A child who knows instinctively that "8 + 8 = 16," for example, can more easily figure out the sum of "8 + 9" by simply adding one to the total.

Use flash cards to stimulate memorization. Try grouping cards by fact families to emphasize the relationships among these numbers. While students should recognize how numbers interact with each other, rote memorization of basic math facts will provide a complementary foundation for moving on to more complicated arithmetic.

Utilizing Word Problems

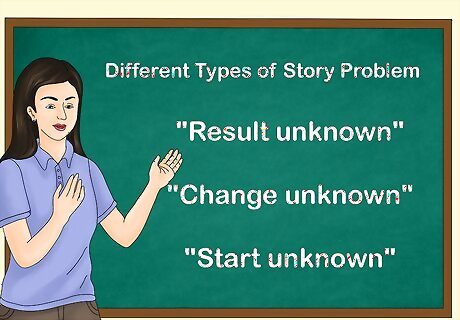

Practice different types of story problems. While some students can find story problems more complex, others will thrive when they better understand the real-world implications of learning addition. Help your child recognize three different situations that require addition: "Result unknown" problems -- for example, if Meredith has two cars and on her birthday she receives three more, how many cars does she now have in all? "Change unknown" problems -- for example, if Meredith has two cars, and after opening all her birthday presents she now has five cars, how many cars did she receive for her birthday? "Start unknown" problems -- for example, if Meredith receives three cars for her birthday and now she has five, how many cars did she have to start off with?

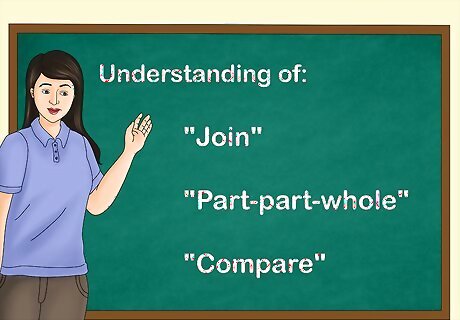

Teach children to recognize "join," "part-part-whole," and "compare" problems. Real-world situations will involve different parameters. Understanding how these work will help your child develop tools to solve addition story problems. "Join" problems involve the growth of a quantity. For example, if Elizabeth bakes three cakes and Sara bakes six more, how many cakes are there altogether? "Join" problems may also ask students to solve for unknown change or start figures -- for example, if Elizabeth bakes three cakes and Elizabeth and Sara produce nine cakes in all, how many cakes did Sara bake? "Part-part-whole" problems involve adding two static figures. For example, if there are 12 girls in the class and 10 boys, how many students are in the class altogether? "Compare" problems" involve an unknown in a compared set of values. For example, if Geoff has seven cookies, and he has three more cookies than Laura, how many cookies does Laura have?

Utilize books that teach addition concepts. Reading- and writing-oriented children may especially benefit from books that incorporate addition themes. Conduct a Web search for "teaching addition with books" to access lists of useful volumes compiled by educators. You can also look for videos on websites like Khan Academy and YouTube.

Comments

0 comment