views

Getting a Job

Determine if the work is right for you. Working on a suicide hotline can be a high-pressure and emotional experience. You may be dealing with multiple stressful situations per shift that require immediate assessment. You may also need to be comfortable with not having any follow-up to your work. That said, there are many benefits to working on a suicide hotline, too, including: Helping people in times of extreme crisis Developing crisis counseling and listening skills Making a difference in your community Providing individuals with community resources for continuing care in their time of need

Research organizations online. Determine what agencies are near you, and/or which particular hotline would be the best fit for your values, schedule, and experience. Some national hotlines partner with local organizations to take their calls. You may need to apply directly with the local agency for a position. There are different types of organizations and ways to connect with those in need: National hotlines such as the US National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline and the Canadian Suicide Crisis Helpline which often work with local crisis centers. The Trevor Project, which provides crisis intervention for LGBTQ youth. Crisis Text Line, a global non-profit which trains persons to work as a crisis counselor in exchange for a commitment to volunteer for 200 hours. The Veterans Crisis Line, which allows Veterans to connect with someone via live chat, text, or phone call.

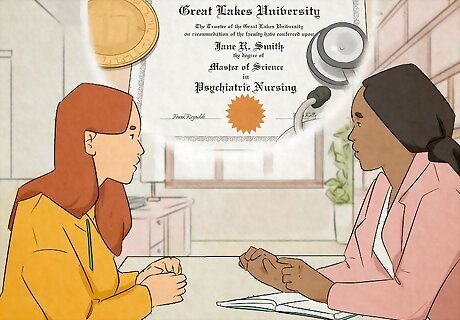

Look for employment. Look for job opportunities through the organizations you are interested in, or look on a job board that caters to your area or skill set. Submit your application per the agency’s requirements, and go on an interview if requested. The qualifications to work as a crisis hotline employee will vary depending on the state and organization you work for, as well as, the level of crisis intervention you are providing. Many organizations will put their new employees through certified training as there are key things or phrases one needs to listen for, or ask questions about to ensure the caller is connected to the most appropriate level of care. If you want to be employed by a crisis hotline, you will likely need, at minimum, a bachelor’s degree in psychology or human services. A master’s degree in a counseling or social work program could further help you take on direct counseling or supervisory roles. Keep in mind that for certain roles within the organization, you may require licensure by your state’s human services regulatory agency. These requirements vary by degree, license, and state.

Apply for a volunteer position. If you have a long-term goal of being employed by a suicide hotline, you can gain experience and skills by working as a volunteer for a suicide or crisis hotline. Having volunteer experience will look great on future employment applications. Check out your local shelters. Domestic violence shelters in particular are always willing to accept volunteers. These places are generally short-staffed and have very little to no funding to pay for another employee. The more free help they can find, the better. In addition, you will get experience providing crisis intervention face-to-face with clients to really hone on your skills. It is always good to start off volunteering for an organization of preference and connect with others with experience. Through this connection, you get a feel of this line of work and decide if it works for you. Also, connecting with an experienced crisis hotline worker, and/or crisis counselor will help you identify what level or type of crisis work you wish to do. There are many different levels, each offering their own set of responsibilities, pay, and different levels of required education and experience. Remember, you can still help at a suicide hotline even if you are not taking calls! Help is always needed for fundraising, events, marketing, and administrative support.

Developing Active Listening Skills

Be open and honest about the “suicide question.” Asking someone if they have a plan to kill themselves does not mean that you are planting a seed in their mind to do it. Do not be afraid to ask “Do you feel suicidal?”; or, “Do you feel like you want to kill yourself?” If the caller responds that they do feel suicidal, continue to ask direct questions to assess the following: Lethality — Dangerousness of the plan, and is there potential for rescue if needed Intent — The level of desire and intent to act on ones suicidal thoughts Caller history — Is there a history of suicidal ideation? Were there actual attempts in the past and thought-out plans, or were these passive suicidal thoughts? Are there self-harming behaviors, and if so what are they? (i.e. cutting, burning, pulling out hair, hitting head on door/wall, etc.). Substance abuse/use history — Do they currently drink alcohol or use drugs? Do they have a personal history or family history of substance abuse? Symptoms — Feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness? Mental health History — Does the person have a history of mental health concerns, current psychosis, delusions, or hallucinations? Medical concerns — Are there any immediate medical concerns that require treatment? Coping skills — Does the person know of any healthy ways they can cope with their feelings? Support system — Who or where are their primary formal and informal support systems? Protective factors — There are some factors that can reduce the likelihood that the person will attempt suicide. Do they have supportive family and friends? Access to medical and mental health care? Other concerns and factors that might cause this crisis— This might include lack of housing, no financial income, loss of loved one, or loss of belongings or employment. Are there other family/friend relationship problems? If a person has a plan, a timeline, and a means to kill themselves, they should be considered high-risk and not left alone. Keep the person talking to you, and take their statements seriously.

Establish trust and rapport. Focus on acknowledging and validating what the person is feeling. The more comfortable a person feels with you, the more they will be willing to disclose and allow you to help. Connect with them in a kind, nonjudgmental way. Keep your opinions to yourself. You may not agree with certain aspects of this person’s lifestyle. If you find yourself feeling judgmental, try putting yourself in their situation. Imagine what you would want to hear from someone if you were in crisis. You could say something like, “I know you took a lot of drugs tonight, but right now, my priority is keeping you safe tonight. Do you have somewhere you can go right now?”

Paraphrase. Paraphrasing means to restate what someone says, usually using different or fewer words. The goal is to understand what the person means. It is beneficial to the listener to see if they were correct in their interpretation of the speaker’s words, and it is beneficial to the speaker to know if they are being understood. For example, the statement “I feel like I can’t get out of bed in the morning. I feel like I can’t stop crying most days,” might be effectively paraphrased as “It sounds like you are feeling very depressed.” Even an incorrect paraphrase can help you achieve better understanding. It shows that you are putting effort into listening to the speaker, and it gives the speaker an easy opportunity to correct the listener. For example, say the listener paraphrases the sentence, “I don’t think I can take it anymore” as, “You sound really tired.” The speaker could correct them and say, “No, I feel miserable and hopeless.” This helps the speaker clarify their feelings, and helps the listener stay on the right track.

Empathize. Having empathy means to be able to understand and identify another person’s emotions, as well as the ability to imagine what the other person may be thinking, feeling, or experiencing. When you empathize with another, you are “putting yourself in their shoes.” Expressing empathy for the other person allows that person to evaluate, clarify, and/or identify their own feelings. The person expressing the empathy may allow the other person to hear their emotion expressed in a different way, bringing further clarity to their emotions. For example, say a caller in crisis is expressing suicidal thoughts because they feel all alone in the world. In the last year, they have had several people close to them die. You could say, “That sounds devastating. You must be grieving these losses so badly right now.” The caller may not have put together that their feelings of loneliness are connected to their grief.

Use “say more” expressions. These are ways to keep the person talking about a particular topic and explore deeper feelings. You can also deploy one of these sentences if you are feeling stuck in a conversation with someone, and you want to keep them talking, but aren’t sure where to go with them yet. These include questions like, “Could you tell me more about what happened?” or statements like, “I’d love to hear more about that.” For example, if someone says, “I just don’t want to live anymore,” you could say, “Could you help me better understand what is making you feel that way?”

Ask open-ended questions. Keep the person talking by limiting your use of “yes” and “no” questions, and instead, asking questions that require the person to explain, describe, and express their emotions. Give them space to answer the questions. Be comfortable with silence. They may be formulating their response. You could ask something like, “How did you feel when your son said that to you?” or, “When you said, ‘I don’t think he ever wants to see my face again,’ what do you mean by that?”

Provide necessary resources. This may include giving the person a referral for ongoing clinical care, support groups, education and information, resources for financial support or finding housing, etc. If the person needs immediate or emergency care, know the protocol to connect them.

Utilizing Your Hotline Training

Follow your agency’s protocol. You will receive a thorough training before becoming a suicide hotline worker. Your training should indicate steps you take in every call, resources available, how to troubleshoot situations, and who to ask if you need help. Make sure you understand all of these steps before you begin taking calls. If you do not understand something, ask. You will receive hands-on training, including participating in role-playing exercises, answering mock phone calls, and watching other workers take calls, before you answer calls on your own. Make sure you follow your agency’s rules on confidentiality, for both you and the client. Some agencies have you use an alias to protect your identity. While it may feel frustrating to not be able to follow-up with the person who called you, understand that it helps you focus on staying in the moment to prevent a crisis, and not dwelling on things you may not be able to change.

Follow your QPR training. QPR (Question, Persuade, and Refer) is a suicide-prevention technique that anyone can learn and use, whether you work in a crisis management capacity or are just a concerned citizen. Those trained in QPR learn suicide warning signs and become “gatekeepers,” or people in a position to recognize a crisis and suicide warning signs. Question the person about suicide directly. Talk to them about any suicidal ideation, plans, timelines, or means. Assess their immediate risk. Persuade the person to get help. Be a supportive listener and empathize with their concerns. Then you could say, for example, “I want to make sure that you have a way to stay safe right now. Who can you call right now who can come over and stay with you?” Refer for help. Assess their support network and other protective factors (relationships and behaviors that reduce likelihood of suicide). Utilize some of these support systems already in place to get them help. Your hotline may have additional resources to which you can connect your caller.

Get training on different populations. Understand that different cultures and groups of people may have different needs and concerns. If you are working in an area that has a large population of a group of people with whom you are not familiar, you may want to have some additional training on common problems and how to work with that particular community. For example, you may want to take additional training courses on how to help suicidal youth, LGBTQ+ individuals, the elderly, or veterans. Check with your organization to see if they offer in-house trainings on different populations, or if they recommend outside organizations that can help you.

Ask for help. If you are on a call trying to manage a difficult situation, or if you feel like you are unable to be an effective helper for this caller, follow your organization’s protocol to get assistance. Remember that different people are more susceptible to different emotional triggers than others. Keep your ego in check. Remember, it’s not about you, it’s about helping the caller survive. Do whatever you can to keep the caller safe, even if that means asking for help.

Prepare for deep emotional impact. Know that in your role as a hotline counselor, you will likely be exposed to many difficult situations. Understand you may even hear a person attempt and/or complete suicide over the phone. Your training will help you develop effective strategies to handle your own emotions while working on the hotline. Connect with other volunteers and supervisors on your hotline to prepare for difficult calls, and to for suggestions on how to take care of yourself after particularly traumatic calls.

Taking Care of Yourself

Talk to other staff members or volunteers. Reach out to other hotline workers who are coping with the same feelings as stresses as you are to talk about your highs, lows, and problems. You may also end up making some new friends. Following a difficult call, connect with a supervisor or other designated person to help you debrief and address any emotional impact. Reaching out for your own help will help keep you strong and focused to continue to help others.

Take a break if needed. If you are feeling drained, emotionally depleted, or overwhelmed with other stressors in your life, talk to a supervisor at your agency. Let them know you need a break. Because of the stressful nature of suicide hotline work, there should be plans in place to help you manage your stress effectively and avoid burnout. Learn to recognize your own signs of burnout. These may include symptoms like fatigue, anxiety, detachment, or depression. You could say, “I have been dealing with so much stress in my life over the past couple of weeks. I don’t think I can do a good job answering calls right now. Can I take a few days off, or work on something that doesn’t require client interaction?”

Practice self-care. Because you will be giving so much of yourself in order to help callers in places of crisis, be sure that you have effective ways of taking care of yourself. Self-care is an intentional action that meets your physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual need. Self-care looks different for different people. Some ways you might consider meeting your self-are needs include: Physical needs: Go for a walk, get a massage, or make a special meal for yourself. Mental needs: Take up a new hobby you’ve always wanted to learn, create an art project, or listen to a podcast about something that interests you. Emotional needs: Listen to music that relaxes or inspires you, make a donation to charity, or attend a support group meeting. Social needs: Call your loved ones, go out to dinner with friends, or smile at strangers and strike up conversations. Spiritual needs: Attend a religious service if you are religious, meditate, pray, or connect with nature.

Comments

0 comment