views

At the time of implementing the Sneha Sparsha scheme, many bureaucrats assumed that it would be applicable only for children from below poverty line (BPL) families. However, Dr Abhijit Sarma, who works closely with Himanta in implementing his flagship schemes, remembers how Himanta shot down this idea. ‘They’re children,’ Himanta told his bureaucrats. ‘They don’t even understand what the poverty line is. All they know is that they have been born with a malformation. How can we discriminate in this manner?’ The matter ended there. The scheme became available for every child in the state. Himanta often went to villages where he found children with malformations, and sent them to Abhijit at GMC so that they could be treated under Sneha Sparsha. Every case was followed up personally, and the doctors were often stunned by Himanta’s medical knowledge. Well-aware of symptoms, side-effects and different ways to treat every condition, the doctors often found themselves on the backfoot when Himanta engaged them about particular cases, using chaste medical jargon. When India received its first PET CT scan machine, capable of detecting cancer and other diseases in the body, Himanta left the head of GMC’s radiology department speechless by telling him that they should have one as well. Himanta immediately proceeded to outline how the unit would work. When it was installed at GMC in 2016, Assam became India’s first state to house such a machine in a government hospital. ‘He keeps up to date with the latest medical journals and watches surgical videos,’ says Abhijit. Abhijit recalls how, on a visit to Bengaluru, Himanta had an intense discussion with the head of NH’s intensive care unit about a particular case. Later, the ICU head pulled Abhijit aside to ask what Himanta’s specialization was.

Abhijit recalls how another important partnership with NH started after he received a picture on WhatsApp from Himanta. It was of a young boy with a bloated stomach. The boy had waited on the footpath next to News Live’s office, one of the television channels run by Himanta’s wife. When she arrived and found him there, she knew something had to be done. Himanta too arrived there a few moments later, took his picture and sent it to Abhijit. The boy was sent to GMC, where they realized that he needed a kidney transplant. He was flown to Bengaluru, and the transplant took place in NH. Himanta and his wife personally footed the bill and took care of all the other expenses. Himanta was traveling in South India the following week and made a special stop at Bengaluru to check on the boy. He was satisfied. Upon returning to Guwahati, a scheme for kidney transplants was created. Similarly, a partnership for liver transplants was established with Kolkata’s RTIICS hospital, and a scheme was created. Liver transplants cost Rs.8 lakh–Rs.9 lakh, but the deal Himanta negotiated allows them to get it done for just over Rs.3,50,000. Another one of Himanta’s pet projects was bringing Mission Smile to Assam. When he took over as Health Minister, cases of cleft lip and cleft palate were widespread across the state. This is a condition wherein children are born with splits in the upper lip or the roof of the mouth, or even both. These defects hinder speech and feeding, and the condition is often passed on genetically. A surgery can restore normal functioning, and Himanta roped in Mission Smile, an organization dedicated to eradicate this condition, under a public–private partnership. A dedicated centre was set up, and American specialists would visit the state to operate upon scores of people with the condition. Soon after, experts from Japan and Malaysia also joined in. Today, courtesy Mission Smile, over 18,000 people have been operated upon. Cleft lip and cleft palate have almost disappeared, especially among those who had lived with it for years. Nowadays, those operated upon are much younger.

Through a maze of such schemes, Himanta has ensured that healthcare is more or less free of cost for most people in the state. Specific sections of the population such as children, specific ailments such as congenital diseases and essential parts of the healthcare system such as diagnosis have been made free of cost. Moreover, through another scheme called Arogya Nidhi, BPL families and those earning less than Rs.10,000 a month are provided a healthcare cover of Rs.1,50,000 per year. Much like Ayushman Bharat, most treatments are included, and several hospitals, not just across the state but across the country, are empanelled. Another such scheme called the Atal Amrit Abhiyan provides an annual healthcare cover of Rs.2 lakh per individual. Although it is aimed at BPL families, even above poverty line families with annual incomes of up to Rs.5 lakh can enroll for a token fee of Rs.100. Similar schemes exist for government servants and their families, whose medical bills are reimbursed within a month. As Health Minister, Himanta often cleared medical bills that were higher than the specified cover for reimbursement, especially if a way to foot someone’s medical expenses could not be worked out through the existing ecosystem of government schemes.

Often, when Himanta traveled outside Assam, he would make it a point to visit healthcare facilities and learn about the best healthcare practices outside his state. He returned only to replicate them at home. Tamil Nadu is supposed to have the best pharmaceutical logistics network in the country. After visiting the state, Himanta got similar warehousing facilities constructed in Assam. One of Rajasthan’s flagship schemes of providing medicines either for free or at highly subsidized rates was also replicated in Assam. Similarly, when Rajasekhara Reddy launched the dial-108 ambulance service in partnership with the Satyam Group for the very first time in Andhra Pradesh, the same service was initiated in Assam. Launched in partnership with the GVK Group in 2008, the service went by the name of ‘108 Mrityunjoy’. At the time of writing this book, the mega project that Himanta seeks to get up and running is Assam’s cancer grid. In partnership with the Tata Trust, the Assam government will create a grid of cancer-care centres across the state linked to apex centres, which are found in the bigger hospitals. Currently, the apex centres are overburdened, and cancer care often doesn’t reach the remotest areas. The centres on the grid will provide diagnosis and care, and will be located much closer to the homes of people who live in far-flung areas. The efficiency of Assam’s healthcare system was tested with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the first wave, Assam emerged as one of the states which passed the test with flying colours. Before the state even reported its first case of the virus, five testing centres were up and running. Guwahati’s Sarusajai Stadium had been converted into a thousand-bed quarantine facility, while other quarantine facilities of similar capacity had been set up across the state, especially in the districts bordering West Bengal. Memorandums of understanding were signed with private hospitals, and in a span of two days, patients from many government hospitals and medical colleges were shifted to these private hospitals. The ones that had been vacated were dedicated exclusively to COVID-19 patients and were prepared accordingly. The state’s capacity in terms of beds and ventilators far surpassed those of neighbouring West Bengal before the virus even reached Assam, drawing much criticism for the neighbouring state. Himanta personally criss-crossed the state, making sure the arrangements were in place. Meanwhile, PPE kits were procured from every source possible. When Mukesh Ambani called Himanta to ask him how he could help, Himanta asked him to donate PPE kits. Ambani promptly arranged 10,000 kits. Himanta’s deputy at the health ministry, Pijush Hazarika, personally flew to Delhi on a chartered flight and returned with another 1,500 kits. Himanta managed to procure 50,000 more from China bending the Assam government’s procurement rules by asking local government contractors to chip in and wait for a reimbursement after the kits arrived. The foreign supplier had refused to send the kits without the entire cost being paid in advance, and the Assam government’s rules disallowed it from paying a 100 per cent advance on any purchase. Finally, the kits were flown in from Hong Kong, and Assam became the first Indian state to directly purchase PPE kits from a foreign country. Deals were made with fivestar hotels across the state to house medical personnel, so that they remained comfortable while being away from home for long durations. When the pandemic finally hit the state, it was evident that the healthcare system was well-oiled. It was nowhere close to being as stretched as some of the other states in the country. Himanta continued to criss-cross the state, personally monitoring the situation, sometimes even donning a PPE kit and entering COVID wards to check on the patients himself. At the end of 2020, Assam had the lowest death rate (0.28 per cent) and the highest recovery rate (98.02 per cent) in the entire country.

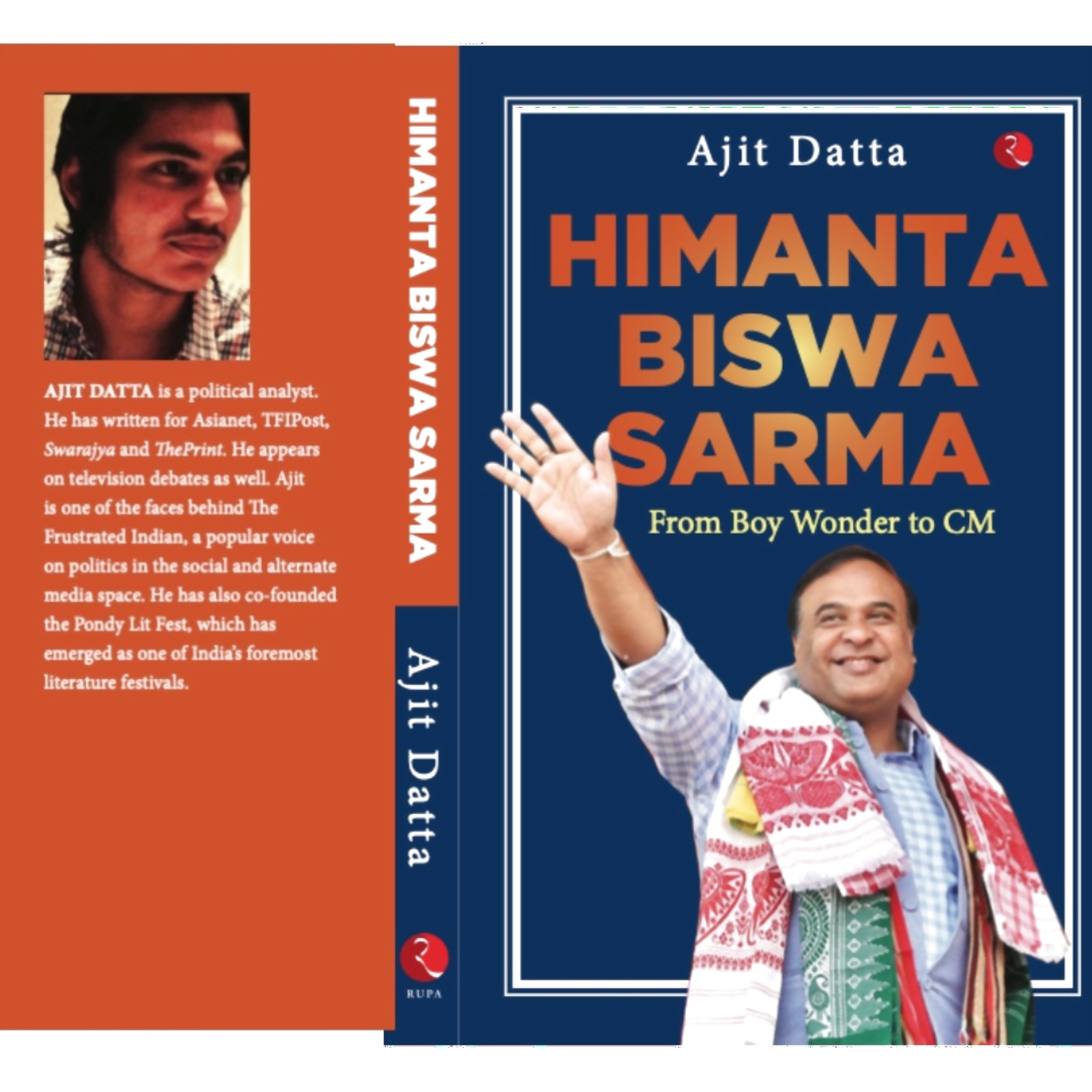

This excerpt from Ajit Datta’s ‘Himanta Biswa Sarma: From Boy Wonder to CM’ has been published with the permission of Rupa Publications.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment