views

BA kiya hai, MA kiya;

Lagta hai voh bhi ainvain kiya;

Kaam nahin hai warna yahaan…

Kishore Kumar had actually crooned this anguishingly raw melody back in 1971, in a Gulzar directorial titled Mere Apne. But surprisingly, recent data from the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) shows just how relevant this tune remains today as well.

India’s unemployment rate rose to 7.83% for April 2022. Only slightly lower at 7.60% in March, it just about begins to reflect the many deep-seated rots that are constantly setting in the Indian employment scenario.

Take, for instance, the persistently downtrending youth participation in the job market. CMIE data suggests that the overall labour participation rate (LPR) of Indians fell from 46% to just 40% between 2017 and 2022. Moreover, an increasing number of women also permanently left the workforce during this time, threatening to tear apart the already fragile fabric of women participation in the economy.

There Are No Jobs

Y, who did not wish to be identified by her full name, graduated from her Masters program in Communications from a reputed Indian university in 2020. With the pandemic at its peak and significant economic destruction and job losses in tow, her batch was told that it was only a matter of time and economic recovery before they land a good, comfortable job that matches their skills and education levels. “Placement drives won’t help at all,” said the college administration.

Cut to 2022, Y is frustrated, desolate and no longer actively seeking a job. “I haven’t been able to move past the basic pay in my brief stints, and it feels demeaning to constantly have to undervalue myself and my skills to earn money. Most of the time, the job profile does not suit my interest and as such, keeping at it for long is a terrible prospect.”

Why not look for other alternatives? “Where are they?” she laments. “Everyone keeps saying that the job market is recovering and that employment is booming back. But that’s far from true. I have applied to many jobs on LinkedIn and otherwise, but companies are walking extremely tightropes while hiring. It is impossible to find a job and pay commensurate to my degree,” she continues.

This might explain why more than half of India’s 900 million workforce is not actively seeking a job at present. And this is true not just for the educated millenia, but for the bulk of semi-skilled workers who managed shops, beauty parlours, gyms and other essential services in pre-Covid days. Post the pandemic, they are finding it hard to get back on their feet.

Naazish, who was a beauty parlour attendant at a popular salon chain in Ghaziabad until 2020, was let go as many establishments shut shop in the wake of the pandemic. Two years of sitting idle at home, she saw a life of financial independence slip right through her hands.

“I tried signing up for online services, but the hours were erratic, and charges and facilities were extremely meagre. I had no choice but to let go of it all,” she says.

Cultural Constraints Too Hard to Bypass

Around 21 million women have permanently left the workforce over the last five years, detailed the CMIE report. As such, the pandemic had already forced them to bear the disproportionate brunt of unpaid domestic work. And now, patriarchal pressures and a less-than-lucrative job market is pulling them away from the sliver of good opportunities that are on offer.

X, who wished to remain anonymous, is a successful communications professional working in Delhi. She details how her parents keep insisting that she quit her job and come back. “They don’t see the value in me being financially independent and empowered. They just want me close to home, within sight. Even if that means no career growth.”

She is planning to return to her hometown, where she believes job opportunities in her professional domain are a “scarcity”.

“I don’t know anymore…” she trails off.

In its most recent Quarterly Employment Survey (QES), the government had noted that nine sectors, including trade, manufacturing and more, created around 4,00,000 jobs between October-December last year.

But then again is the question of rising inflation, which is currently at 6.95%, that potentially eats into generally paltry salaries, thereby perpetuating a vicious cycle where just nothing is enough.

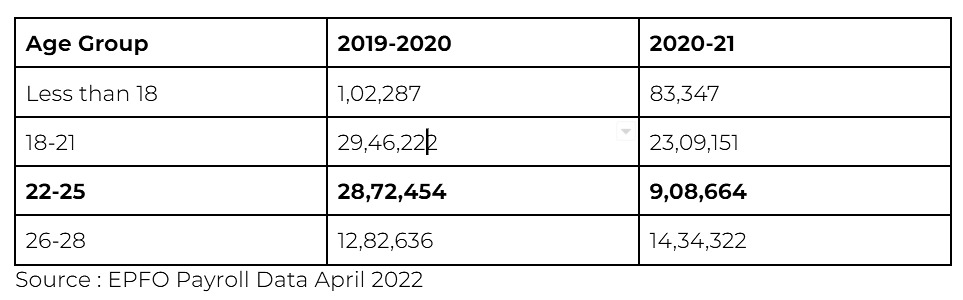

From 39.9% in February to 39.5% in March, what may seem like a tiny blip in India’s LPR actually has significant implications. Even the Employee Provident Fund (EPF) data, considered a barometer for general employee measurement in India, has been dipping worryingly low for the past year. Consider this:

What awaits the Indian employment scenario? For a country that prides on being young, the situation currently reeks of the young dejected at and rejecting the not-so-solid job market.

Read all the Latest Business News here

Comments

0 comment