views

X

Research source

Over time, an understanding has developed of how musical sounds are made and organized. While you don’t have to know everything about musical scales, rhythms, melodies, and harmonies in order to make music, an understanding of some of the concepts will help you appreciate and make better music.

Sounds, Notes, and Scales

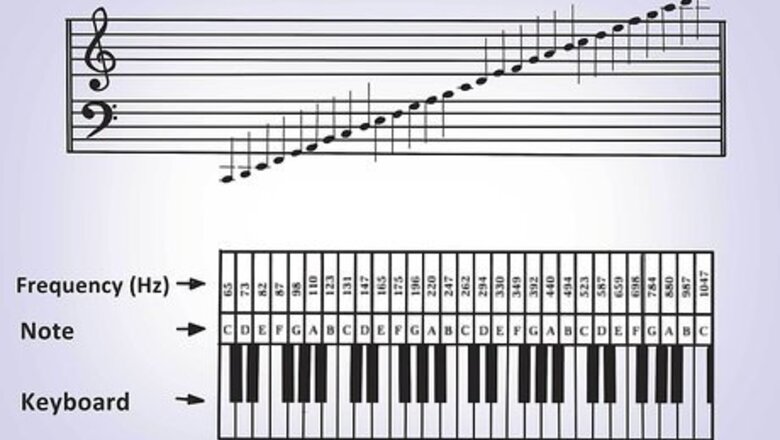

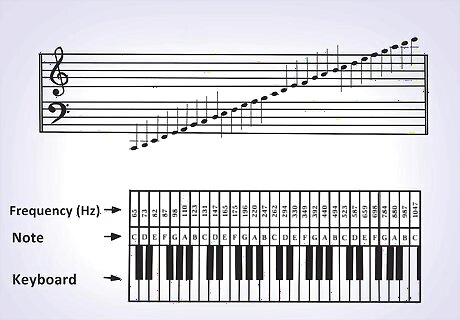

Understand the difference between “pitch” and “note.” These terms describe qualities of musical sounds. Although the terms are related, they are used somewhat differently. “Pitch” refers to the sensation of lowness or highness associated with the frequency of a given sound. The greater the frequency, the higher the pitch. The frequency difference between any two pitches is called an “interval.” “Note” refers to a named range of pitches. The standard frequency for A above middle C is 440 hertz, but some orchestras use a slightly different standard, such as 443 hertz, to produce a brighter sound. Most people can determine whether a note sounds right when played against another note or in part of a series of notes in a piece of music they recognize. This is called “relative pitch.” A few people possess “absolute pitch” or “perfect pitch,” which is the ability to identify a given pitch without hearing a reference pitch.

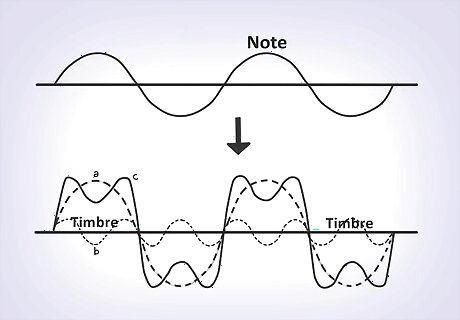

Understand the difference between “timbre” and “tone.” These sound terms are generally used with respect to musical instruments. “Timbre” refers to the combination of primary pitch (fundamental) and secondary pitches (overtones) that sound whenever a musical instrument plays a note. When you pluck the low E string on an acoustic guitar, you actually hear not only the low E note, but also additional pitches at frequencies that are multiples of the low E frequency. The combination of these sounds, which are also collectively called “harmonics,” are what makes one instrument sound different from another kind of instrument. “Tone” is a somewhat more nebulous term. It refers to the effect the combination of fundamental and secondary harmonics have on the listener’s ear. Adding more high-pitched harmonics to the timbre of a note produces a brighter or sharper tone, while damping them produces a more mellow tone. “Tone” also refers to an interval between two pitches, also called a whole step. Half this interval is called a “semitone” or half-step.

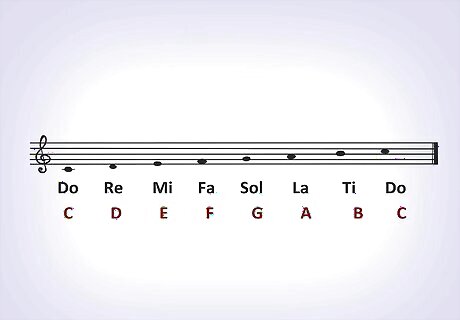

Assign names to notes. Music notes can be named in several ways. Two methods are commonly used in most of the Western world. Letter names: Notes of certain frequencies are assigned letter names. In English and Dutch-speaking countries, the letters run from A to G. In German-speaking countries, however, “B” is used for the B-flat note (the black piano key between the A and B keys), and an “H” is used to represent the B-natural note (the white B key on a piano). Solfeggio (also called “solfege” or “solfeo”): This system, familiar to fans of ‘’The Sound of Music,’’ assigns one-syllable names to notes according to their successive positions within a scale. The original system developed by 11th century monk Guido d’Arezzo used “ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si,” taken from the first words of lines in a chant to St. John the Baptist. Over time, “ut” was replaced with “do,” while some shorten “sol” to “so” and sing “ti” instead of “si.” (Some parts of the world use the solfeggio names the way the Western world uses letter names.)

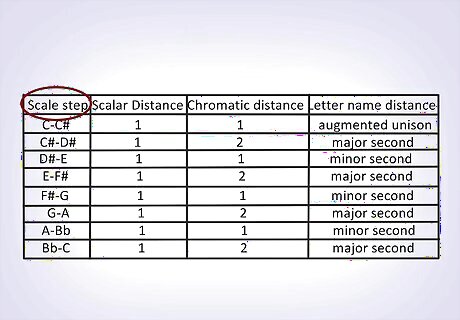

Organize a series of notes into a scale. A scale is a series of successive intervals between pitches such that the highest pitch is at twice the frequency of the lowest pitch. This range is called an octave. These are some of the common scales: A full chromatic scale uses 12 half-step intervals. Playing an octave on the piano from middle C to the C above middle C, sounding all the white and black keys in between, produces a chromatic scale. Other scales are more restricted forms of this scale. A major scale uses seven intervals: The first and second are whole steps; the third is a half-step; the fourth, fifth, and sixth are whole steps; and the seventh is a half-step. Playing an octave on the piano from middle C to the C above, sounding only the white keys, is an example of a major scale. A minor scale also uses seven intervals. The most common form is the natural minor scale. Its first interval is a whole step, but the second is a half-step, the third and fourth are whole steps, the fifth is a half-step, and the sixth and seventh are whole steps. Playing an octave on the piano from A below middle C to A above middle C, sounding only the white keys, is an example of a natural minor scale. A pentatonic scale uses five intervals. The first interval is a whole step, the next is three half-steps, the third and fourth are each a whole step, and the fifth is three half-steps. (In the key of C, this means the notes used are C, D, F, G, A, and C again.) You can also play a pentatonic scale by playing only the black keys between middle C and high C on a piano. Pentatonic scales are used in African, East Asian, and Native American music, as well as in folk music. Major scales are more uplifting and happy, while minor scales have a darker, more serious tone. The lowest note in the scale is called the “key.” Usually, songs are written such that the last note of the song is the key note; a song written in the key of C almost always ends on the note C. A key name typically also includes whether the song is played under a major or minor scale; when the scale isn’t named, it’s understood to be the major scale.

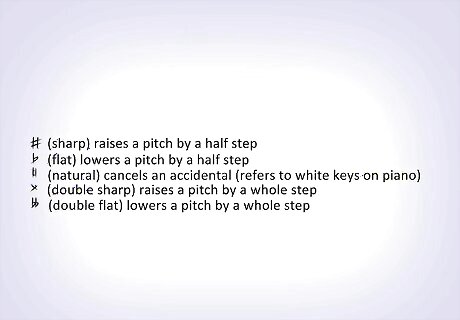

Use sharps and flats to raise and lower note pitches. Sharps and flats raise and lower the pitches of notes by a half-step. They are necessary when playing in keys other than C-major or A-minor to keep the interval patterns for major and minor scales correct. Sharps and flats are indicated in lines of written music with symbols called accidentals. A sharp symbol, which resembles the hashtag (#), placed in front of a note raises its pitch by a half-step. In the keys of G-major and E-minor, the F is raised by a half-step to become F-sharp. A flat symbol, which resembles a pointed lowercase “b,” placed in front of a note lowers its pitch by a half-step. In the keys of F-major and D-minor, the B is lowered by a half-step to become B-flat. For the sake of convenience, the notes that must always be sharped or flatted in a particular key are indicated at the beginning of each line in the music staff in the key signature. Accidentals then have to be used only for notes outside the major or minor key the song is written in. When accidentals are used this way, they apply only to occurrences of that note before the vertical line that separates measures. A natural symbol, which looks like a vertical parallelogram with a vertical line extending up and down from two of its vertices, is used in front of any note that would be otherwise be sharped or flatted to show that it shouldn’t be at that place in the song. Naturals never appear in key signatures, but a natural can cancel the effect of a sharp or flat used within a measure.

Beats and Rhythms

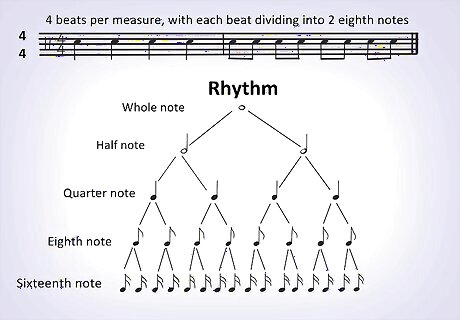

Understand the difference between “beat,” “rhythm,” and “tempo.” These terms are also closely related. “Beat” refers to an individual pulse of music. A beat can be either a sounded note or a period of silence called a rest. A beat can also be divided among multiple notes, or multiple beats can be assigned to a single note or rest. “Rhythm” refers to a series of beats or pulses. The rhythm is determined by how the notes and rests are arranged within a song. “Tempo” refers to how fast or slowly a song is played. The faster the tempo, the more beats are played per minute. “The Blue Danube Waltz” has a slow tempo, while “The Stars and Stripes Forever” has a faster tempo.

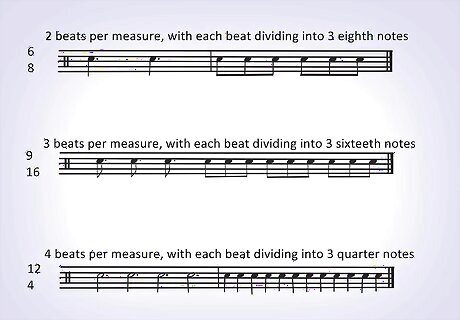

Group beats into measures. Measures are groups of beats. Each measure has the same number of beats. The number of beats each measure has is indicated in written music with a time signature, which looks like a fraction without a line separating the numerator and denominator. The top number indicates the number of beats per measure. This number is usually a 2, 3, or 4, but may be as high as 6 or higher. The bottom number indicates what kind of note gets a full beat. When the bottom number is a 4, a quarter note (looks like a filled oval with a line attached to it) gets a full beat. When the bottom number is a 2, a half note (looks like an open oval with a line attached to it) gets a full beat. When the bottom number is an 8, an eighth note (looks like a quarter note with a flag attached to it) gets a full beat.

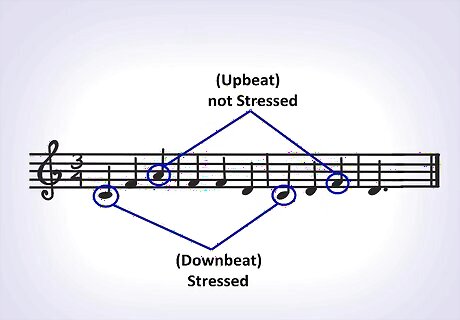

Look for the stressed beat. Rhythms are determined according to which beats in the measure are accented (stressed) and which beats are not (unstressed). In most pieces of music, the first beat, or downbeat, is stressed. The remaining beats, or upbeats, are not stressed, although in a measure of four beats, the third beat may be stressed, but to a lesser degree than the downbeat. Stressed beats are also sometimes called strong beats, while unstressed beats are sometimes called weak beats. Some pieces of music stress beats other than the downbeat. This type of stressing is known as syncopation, and beats so stressed are called back beats .

Melody, Harmony, and Chords

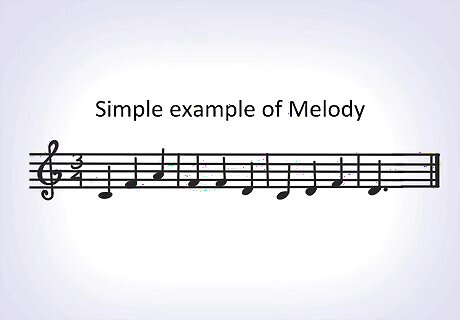

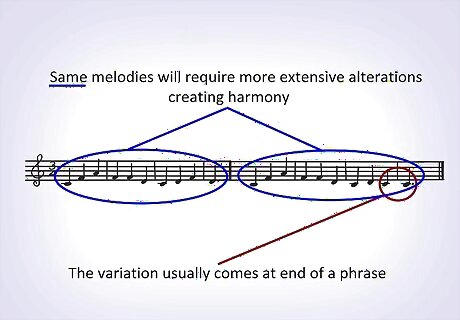

Define the song with its melody. “Melody” is a succession of notes that the person listening to identifies as being a coherent song, based on the pitches of the notes and rhythm with which they are played. Melodies are composed of phrases, which are groups of measures. These phrases may repeat throughout the melody, as in the Christmas carol “Deck the Halls,” where the first and second lines use the same sequence of measures. A common melodic song structure is to have one melody for a verse and a related melody serve as a chorus or refrain.

Accompany the melody with harmony. “Harmony” is the playing of notes outside those of the melody to either enhance or contrast its sound. As noted earlier, many stringed instruments actually generate multiple tones when plucked; the overtones that sound with the fundamental tone are a form of harmony. Harmony can be achieved through the use of musical phrases or chords. Harmonies that enhance the sound of the melody are called “consonant.” The overtones that sound with the fundamental tone when the string of a guitar is plucked are a form of consonant harmony. Harmonies that contrast with the melody are called “dissonant.” Dissonant harmonies can be created by playing several contrasting melodies at once, such as when singing “Row Row Row Your Boat” as a round, where each group starts singing at a different time. Many songs use dissonance as a way to express unsettled feelings and gradually work toward consonant harmonies. In the example of the round of “Row Row Row Your Boat” above, as each group finishes singing its verse for the last time, the song becomes calmer until the last group sings “Life is but a dream.”

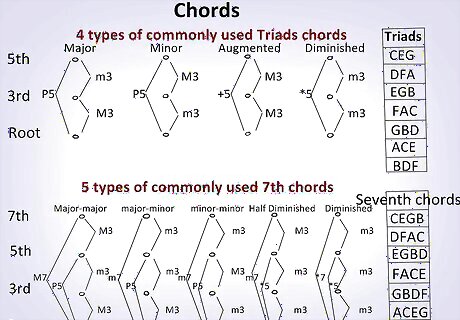

Stack notes to form chords. A chord is formed when three or more notes are sounded, usually at the same time, but not always. The most common chords are triads (three notes) where each successive note is two notes up from the previous note. In a C major chord, the notes are C (the chord root), E (the major third), and G (the fifth). In a C minor chord, the E is replaced with an E-flat (the minor third). Another commonly used chord is the seventh chord, in which a fourth note is added to the triad, the seventh note up from the root. A C major seventh chord adds a B note to the C-E-G triad to make the sequence C-E-G-B. Seventh chords are more dissonant than triads. It is possible to use a different chord for each individual note in a song; this is how barbershop quartet harmony is created. More commonly, however, chords are paired with notes found in the chord, such as playing a C major chord to accompany the E note in a melody. Many songs are played with just three chords, those whose root notes are the first, fourth, and fifth notes in a scale. These chords are represented with the Roman numerals I, IV, and V. In the key of C major, these chords would be C major, F major, and G major. Often, a seventh chord is substituted for a V major or minor chord, so that when playing in C major, the V chord would be a G major seventh. The I, IV, and V chords are interrelated between keys. While the F major chord is the IV chord in the key of C major, the C major chord is the V chord in the key of F major. The G major chord is the V chord in the key of C major, but the C major chord is the IV chord in the key of G major. This interrelationship carries through the rest of the chords and can be mapped as a diagram called the circle of fifths.

Types of Musical Instruments

Strike or scrape a percussion instrument to make music with it. Percussion instruments are considered one of the oldest forms of musical instrument. Most are used to create and keep rhythm, although a few can play the melody or create harmonies. Percussion instruments that produce sound by vibrating their entire bodies are called idiophones. These include instruments that are struck together, such as cymbals and castanets and those that are struck by something else, such as steel drums, triangles, and xylophones. Percussion instruments with a “skin” or “head” that vibrates when struck are called membranophones. These include drums such as the timpani, tom-tom, and bongo, as well as instruments that attach a string or stick to the membrane that vibrates it when pulled or rubbed, such as the lion’s roar or cuica.

Blow into a woodwind instrument to make music with it. Woodwind instruments produce sound by vibrating when blown. Most include tone holes to change the pitch of the sound they produce, thus making them suited for playing melodies and harmonies. Woodwinds are divided into two types: flutes, which produce sound by making the entire instrument body vibrate, and reed pipes, which vibrate material placed inside the instrument. These are further divided into two sub-types. Open flutes produce sound by splitting an airstream blown over the edge of the instrument. Concert flutes and panpipes are types of open flute. Closed flutes channel air through a duct in the instrument to split it and make the instrument vibrate. The recorder and organ pipes are types of closed flute. Single-reed instruments place a reed into the instrument mouthpiece. When blown into, the reed vibrates the air inside the instrument to produce sound. Clarinets and saxophones are examples of single-reed instruments. (Although a saxophone’s body is made of brass, it is considered a woodwind instrument because it uses a reed to make its sound.) Double-reed instruments use two cane reeds bound together at one end instead of a single reed. Instruments such as the oboe and bassoon put the double reed directly between the player’s lips, while instruments like the crumhorn and bagpipes keep their double reeds covered.

Blow into a brass instrument with closed lips to make music with it. Unlike woodwind instruments, which rely solely on directing a stream of air, brass instruments vibrate along with the player’s lips to make their sound. While brass instruments are so named because most of them are made of brass, they are grouped according to their ability to change their sound by changing the distance through which the stream of air must travel before exiting. This is done through one of two methods. Trombones use a slide to change the distance the airstream must travel. Pulling the slide out lengthens the distance, lowering the tone, while pushing it in shortens the distance, raising the tone. Other brass instruments, such as the trumpet and tuba, use a set of valves shaped like either pistons or keys to extend or shorten the airstream length within the instrument. These valves may be pressed singly or in combination to produce the desired sound. Woodwind and brass instruments are often grouped together as wind instruments, since both must be blown into to make music.

Make the strings on a string instrument vibrate to make music with it. The strings of string instruments can be made to vibrate in one of three ways: by being plucked (as with a guitar), by being struck (as with a hammered dulcimer or the key-operated hammers on a piano), or by being sawed (as with the bow on a violin or cello). Stringed instruments can be used for either rhythmic or melodic accompaniment, and can be divided into three categories: Lutes are string instruments with a resonating body and a neck, such as violins, guitars, and banjos. They feature strings of equal length (except the low string on a five-string banjo) and varying thickness. Thicker strings produce a low tone, while thin strings produce a higher tone. Strings may be pinched off at marked points (frets) to effectively shorten them and raise their pitches. Harps are string instruments whose strings are bound in a frame. Harps typically have strings of progressively shorter length arranged vertically, with the bottom end of the string connected to the resonating body, or soundboard. Zithers are string instruments that are mounted onto a body. Their strings may be strummed or plucked, as with the autoharp, or struck directly, as with the hammered dulcimer, or indirectly, as with the piano.

Comments

0 comment