views

Making Initial Checks

Check the patient's name. Above all else, make sure you are looking at the correct chest x-ray first. This sounds obvious, but when you are stressed and under pressure you can skip some of the basics. If you have the wrong x-ray you will be wasting time not saving it.

Look up the patient's history. When you are preparing to read an x-ray make sure you have all the information on the patient, including age and sex, and their medical history. Remember to compare with old x-rays if there are any.

Read the date of the radiograph. Make special note of the date when comparing older radiographs (always look at older radiographs if available). The date the radiograph is taken provides important context for interpreting any findings.

Assessing the Film Quality

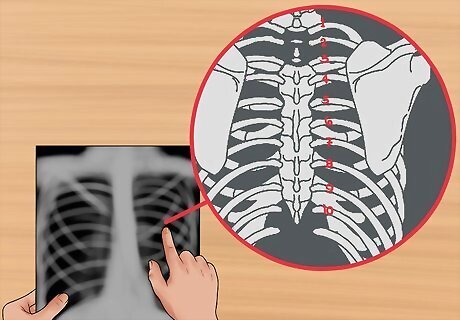

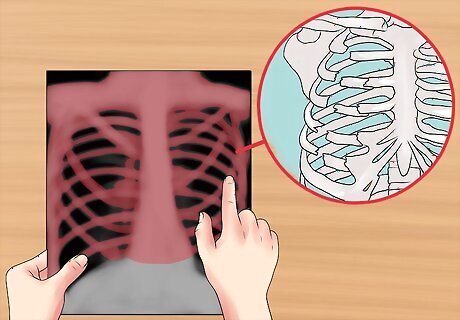

Check if the film was taken under full inspiration. Chest x-rays are generally taken when the patient is in the inspiratory phase of the respiration cycle, in layman's termed having breathed in. This has an important effect on the quality of the x-ray. When the x-ray beams pass through the anterior chest onto the film, it is the ribs closest to the film, the posterior ribs, that are the most apparent. You should be able to view ten posterior ribs if it was taken under full inspiration. If you can see 6 anterior ribs, then the film is of a very high standard.

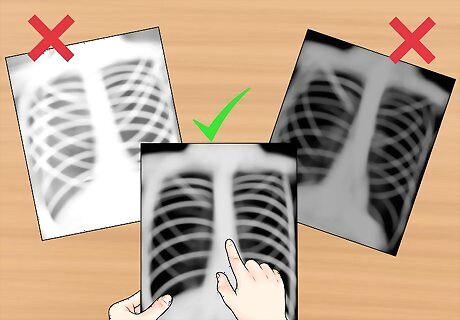

Check the exposure. Overexposed films look darker than normal, and fine details are very difficult to see. Underexposed films look whiter than normal, and cause the appearance of areas of opacification. Look for intervertebral bodies in a properly penetrated chest x-ray. An under-penetrated chest x-ray cannot differentiate the vertebral bodies from the intervertebral spaces. It is under penetrated if you can't see the thoracic vertebrae. An over-penetrated film shows the intervertebral spaces very distinctly.

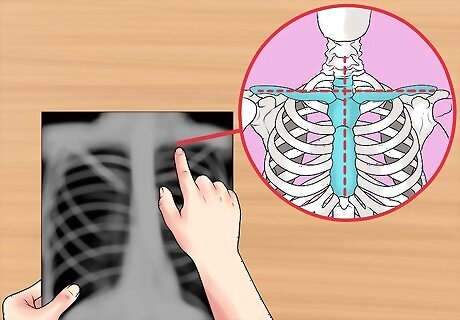

Check for rotation. If the patient was not completely flat against the cassette, there may be some rotation evident on the x-ray. If this has happened the mediastinum can look very unusual. You can check for rotation by looking at clavicular heads and thoracic vertebral bodies. Check that the thoracic spine aligns in the centre of the sternum and between the clavicles. Check if the clavicles are level.

Identifying and Aligning the X-Ray

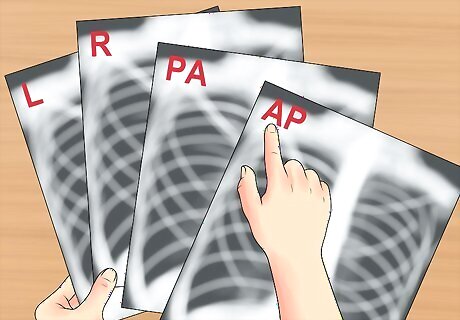

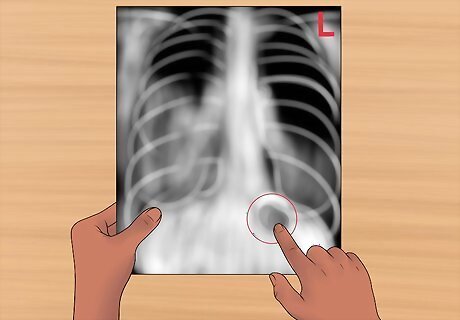

Look for markers. The next thing to do is identify the position of the x-ray and align it correctly. Check for the relevant markers printed on the radiograph. 'L' for Left, 'R' for Right, 'PA' for posteroanterior, 'AP' for anteroposterior, etc. Note the position of the patient: supine (lying flat), upright, lateral, decubitus. Check for and mentally notate each side of the chest x-ray.

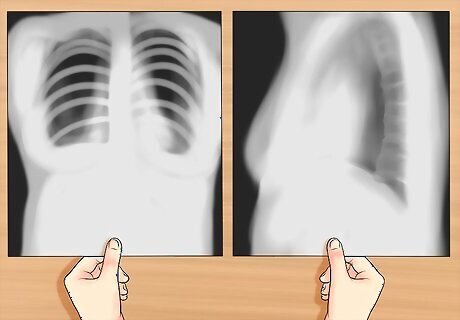

Position the posteroanterior and lateral x-rays. A normal chest x-ray will consist of both posteroanterior (PA) and lateral films which are read together. Align them so they are viewed as if the patient were standing in front of you, so their right side would be facing your left. If there are old films available you should hang these adjacent. The term posteroanterior (PA) refers to the direction of the x-ray traversing the patient from posterior to anterior, from back to front. The term antero-posterior (AP) refers to the direction of the x-ray traversing the patient from anterior to posterior, from front to back. The lateral chest radiograph is taken with the patient's left side of chest held against the x-ray cassette. An oblique view is a rotated view in between the standard front view and the lateral view. It is useful in localizing lesions and eliminating superimposed structures.

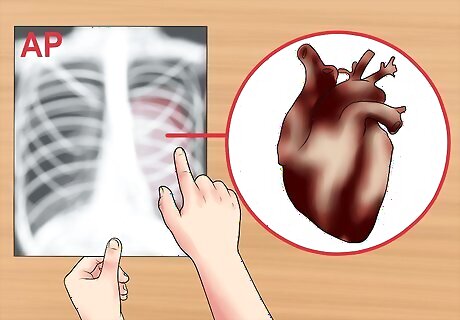

Recognise an antero-posterior (AP) x-ray. Sometimes AP x-rays are taken, but usually only for patients who are too ill to stand up straight for the PA x-ray. AP radiographs are generally taken at shorter distance from the film compared to PA radiographs. Distance diminishes the effect of beam divergence and the magnification of structures closer to the x-ray tube, such as the heart. Since AP radiographs are taken from shorter distances, they appear more magnified and less sharp compared to standard PA films. An AP film can show magnification of the heart and a widening of the mediastinum.

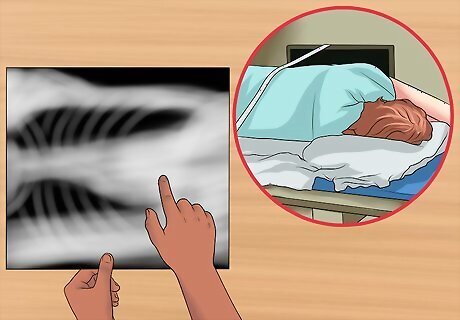

Determine if it is from a lateral decubitus position. An x-ray from this view is taken with the patient lying down on the side. It helps to assess suspected fluid (pleural effusion), and demonstrate whether the effusion is loculated or mobile.You can look at the non-dependent hemithorax to confirm a pneumothorax. The dependant lung should increase in density. This is due to atelectasis from the weight of the mediastinum putting pressure on it. If this doesn't happen it is an indicator of air trapping.

Align left and right. You need to make sure you are looking at it the right way. You can do this easily and quickly by looking for the gastric bubble. The bubble should be on the left. Assess the amount of gas and location of the gastric bubble. Normal gas bubbles may also be seen in the hepatic and splenic flexures of the colon.

Analyzing the Image

Start with a general overview. Before you go on to focus on the specific details, it's good practice to take an overview. The major things that you might have skipped over may change the baseline normals you adopt as reference points. Beginning with this overview may also sensitize to look for particular things. Technicians often use what is called the ABCDE method: check the airway (A), bones (B), cardiac silhouette (C), diaphragm (D) and lung fields and everything else (E).

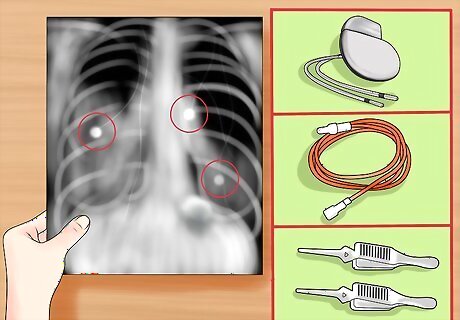

Check if there are any instruments such as tubes, IV lines, EKG leads, pacemaker, surgical clips, or drains.

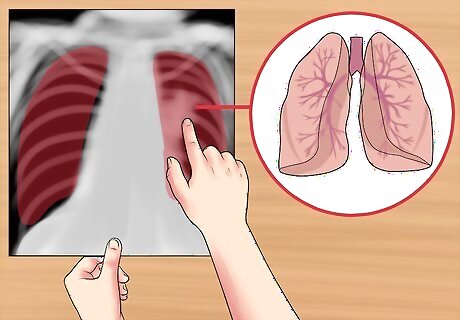

Check the airway and lung fields. Check to see if the airway is patent and midline. For example, in a tension pneumothorax, the airway is deviated away from the affected side. Look for the carina, where the trachea bifurcates (divides) into the right and left main stem bronchi. When checking the lung fields, start by checking the symmetry and look for any major areas of abnormal lucency or density. Train your eyes to peer through the heart and upper abdomen to the lung posterior. You should also be examining for vascularity, and the presence of any mass or nodules. Examine the lung fields for any infiltration, fluid, or air bronchograms. If fluid, blood, mucous, or tumor, etc. fills the air sacs, the lungs will appear radiodense (bright), with less visible interstitial markings.

Check the bones. Look for any fractures, lesions, or defects. Note the overall size, shape, and contour of each bone, density or mineralization (osteopenic bones look thin and less opaque), cortical thickness in comparison to medullary cavity, trabecular pattern, presence of any erosions, fractures, lytic or blastic areas. Look for lucent and sclerotic lesions. A lucent bone lesion is an area of bone with a decreased density (appearing darker); it may appear punched out compared to surrounding bone. A sclerotic bone lesion is an area of bone with an increased density (appearing whiter). At joints, look for joint spaces narrowing, widening, calcification in the cartilages, air in the joint space, and abnormal fat pads.

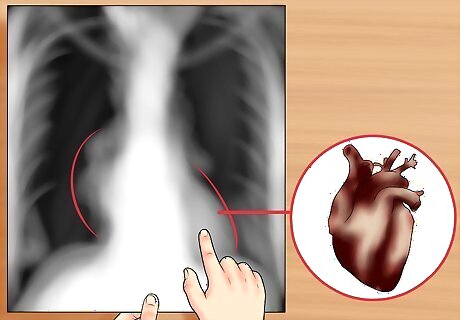

Check the heart and look for the cardiac silhouette sign. Examine the edges of the heart; the silhouette margins should be sharp. Observe whether a radiopacity is obscuring the heart's border, in the right middle lobe and left lingula pneumonia, for example. Also, look at the external soft tissues for any abnormalities. The silhouette sign is basically the elimination of the silhouette or loss of lung/soft tissue interface, that occurs after a mass or flood in the lung. Look at the size of the cardiac silhouette (white space representing the heart, situated between the lungs). A normal cardiac silhouette occupies less than half the chest width. A heart with a diameter greater than half thoracic diameter is an enlarged heart. Note the lymph nodes, look for subcutaneous emphysema (air density below the skin), and other lesions. Look for water-bottle-shaped heart on PA plain film, suggestive of pericardial effusion. Get an ultrasound or chest Computed Tomography (CT) to confirm.

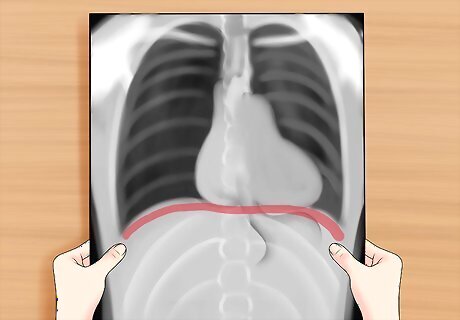

Check the diaphragm. Look for a flat or raised diaphragm. A flattened diaphragm may indicate emphysema. A raised diaphragm may indicate area of airspace consolidation (as in pneumonia) making the lower lung field indistinguishable in tissue density compared to the abdomen. The right diaphragm is normally higher than the left, due to the presence of the liver below the right diaphragm. Also look at the costophrenic angle (which should be sharp) for any blunting, which may indicate effusion (as fluid settles down).

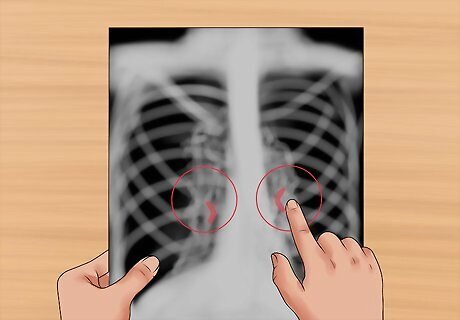

Observe the hila. Look for nodes and masses in the hila of both lungs. On the frontal view, most of the hila shadows represent the left and right pulmonary arteries. The left pulmonary artery is always more superior than the right, making the left hilum higher. Look for calcified lymph nodes in the hilar, which may be caused by an old tuberculosis infection.

Comments

0 comment