views

X

Research source

Proving the Defendant Made a False Statement

Show that a statement of fact was made. Opinions or jokes, no matter how rude or insulting, do not qualify as defamatory. For example, if someone says that they think you're unprofessional and have a bad attitude, that statement can't serve as the basis of a defamation claim, because it's just their opinion – not a statement of demonstrable fact. On the other hand, if someone said you were absent from work three days out of every five, when in fact you had perfect attendance, that statement might support a defamation claim. A statement about your attendance rate is a statement of fact, even if in this case it also happened to be a false statement.

Provide evidence of the statement's falsity. Not only must the statement have been factual rather than a matter of opinion, it must have been false. Relating a true story cannot be defamatory, no matter how embarrassing it may be for you. You must be able to prove that the statement of fact is false. To use the previous example, suppose the person made a negative statement about your attendance record at work. If you in fact had perfect attendance, you would likely be able to prove the statement of fact was false. You would simply collect your personnel file from your employer's human resources department.

Show that the statement was published. This means that at least one person other than yourself must have heard or seen the statement. In other words, if someone posts something on a social media account that includes a false statement of fact about you, that post qualifies as being published if that person's account is publicly accessible or has even one follower (other than yourself). Particularly if the statement was published online, you need a record of it in case the person who published it deletes it later or moves it to a different location. Identify your own account, and describe how you first learned of the statement or when you first saw it or read it. If someone else informed you of the statement, include their name, their contact information, and what they said to you about the statement. A defamatory statement can be spoken, written, or even gestured. However, since statements in print tend to last longer, judges and juries may consider them more harmful than something merely spoken. Having the statement recorded in print means it can harm you repeatedly, while something spoken only once would lose its power over time. Statements that exist in print may be easier to document than something that was spoken. If only a few people heard the verbal statement, it may be very difficult to prove it occurred, especially if the person denies having said it.

Find witnesses who saw or heard the statement. If the statement was spoken rather than printed, witnesses may be your best proof that the statement was made. Try to interview witnesses as soon as possible after they hear or read the statement while it's still fresh in their minds. If they later hear or see any additional information related to the statement and its effect on you, they can update their own statements to include that new information. If the defamatory statement took place in a private conversation, it can be more difficult to prove it took place and that harm to you occurred as a result.

Take screenshots of the statement and any accompanying comments or replies. If the statement was made online, document any further comments or replies to the post after it initially appeared. If the defendant replies to a published comment, they may exacerbate the initial defamation.

Make a list of everyone who could have seen or heard the statement. The more people who had access to the statement, the greater the possible damage to you, depending on your reputation with those people. For example, if you are a teacher, and the defamatory statement was made on your school's Facebook page, you would want to enumerate the people who follow that page and classify them as parents, teachers, alumni, students, or other community members. Generally, if a statement was made publicly, and a large number of people saw it or heard it, it will be easier for you to prove that you suffered harm as a result of the statement. On the other hand, if the person made the statement to just one or two people, proving you suffered harm may turn on who those people are and the power they hold over you. The person may have made the defamatory statement to just one individual. In this case defamation is harder to prove. If, however, the individual happened to be your boss, and your boss fired you as a result of the statement, you might have a case for defamation.

Proving the Statement Caused You Injury

Show the statement was made "knowingly or recklessly." In some jurisdictions a statement is presumed to have caused harm if it was made knowingly or recklessly. This means that the person was aware that their statement could cause you harm. In other jurisdictions, you must show that the person knew the statement was false – or at least neglected to evaluate the truth of the statement. In this situation, if the person had a good-faith belief that the statement was true, they would not be held liable for defamation. Whether good faith negates a speaker's liability also depends on the context of the statement and the role of the speaker. If you have any questions about whether the person who defamed you is protected by their good-faith belief in the statement's truth, consider speaking with an attorney. A personal injury attorney experienced in defamation cases will be able to explain any viable defenses the person might have against your claim.

Line up witnesses. Friends, neighbors, or co-workers can provide a good description of the harm you suffered as a result of the defamation. Witnesses to your harm need not have seen or heard the statement itself. For example, a co-worker might testify that you left work early after learning about the statement and subsequently missed several days of work.

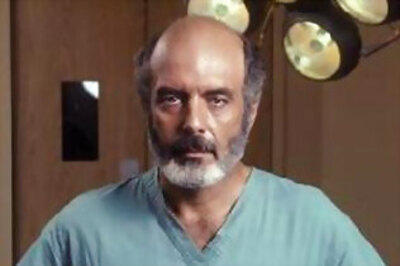

Consider using expert witnesses. If you are alleging that you suffered psychological damages as a result of the defamatory statement, a psychiatrist or other psychological professional can provide the best evidence of your harm.

Show harm to your reputation. Witnesses as well as events can demonstrate such harm. In the U.S., some states consider certain statements to be defamatory "per se," in that they are so awful, they are automatically presumed to have caused harm. For example, if someone stated falsely that you had been convicted of rape, that statement would be considered per se defamation in many states. If the statement is per se defamation, you won't necessarily have to prove any particular damages. In most defamation cases, the primary harm will be to your reputation. For example, if you are a salesman, and someone makes the statement that you cheated your customers, that would potentially damage your reputation as a salesman and cause you to lose customers.

Gather documentation of monetary and other actual losses. If you lost business or suffered other monetary damages as a result of the defamatory statement, calculate the amount of the losses from copies of bills or other financial statements. For example, if you have a letter from a client indicating that they were going to renew their contract with you until they heard the defamatory statement, that letter might serve as evidence of monetary losses you suffered as a result of the defamation.

Following Proper Court Procedures

Consider consulting an attorney. Defamation is a tort, a part of personal-injury law, and a personal injury attorney with experience in defamation claims can help you understand the law and navigate the court system. You may be able to search the website of your state or county bar association to find an attorney experienced in defamation law. You can also refer to directories published by the American Bar Association or other attorney groups. When considering an attorney, find out how many defamation lawsuits they have filed and the outcomes of those suits. Be aware that most civil lawsuits (including defamation cases) reach settlement before trial. Learn what other kinds of cases the attorney typically takes and how many cases they work on at any given time. You want to have a good idea of how much time they intend to spend on your case, and whether they will be handling it personally or delegating the work to assistants or other staff. Before you hire an attorney, get a payment plan or fee schedule in writing, especially if the attorney is asking for an initial deposit. They should be able to give you a detailed accounting of all fees and costs associated with your case. Clearly understand the attorney's goals and strategies for your case. Don't hire an attorney if your goals don't match theirs, or if you're not comfortable with the way they intend to handle your case. For example, if you want to maintain an amicable relationship with the person who defamed you, perhaps because you still have to work with them, don't hire an attorney who will be contentious, confrontational, or overly aggressive.

Check your state's defamation law. Each state recognizes certain contexts in which statements are privileged, thus protecting the speaker/writer from liability for defamation. If the statement was privileged, you might not be able to sue for defamation, even if the statement meets all other requirements. In certain circumstances, the law grants privilege to a wide range of statements. In such situations honesty and openness are deemed more important than the possibility of defamation. A common example of a privileged statement would be one made while under oath as a witness in court or in a deposition. Although a witness may be guilty of perjury for making a false statement under oath, they would not be liable for defamation in that case, because such a statement is considered privileged. Privileged circumstances vary among states. For example, many states recognize a qualified form of privilege for individuals acting as employment references while giving information to prospective employers.

Make sure you're suing in the appropriate court. To win a defamation case you must bring suit in the court that has power over the subject matter of your suit and the person you are suing. This usually means that you must sue in a court located in the city or county resided in by the person you're suing. If they do not live in your state, you may choose to file in a federal court. The court must have the power to hear your suit, an authority referred to as "subject matter jurisdiction." Jurisdiction also depends on the amount of money in contention. For example, small-claims courts deal only with cases where a small amount of money is at stake, typically less than $5,000.

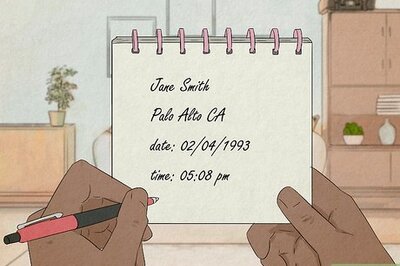

File your lawsuit before the statute of limitations has passed. Each state defamation law recognizes a statute of limitations, providing a time deadline for filing suit. If the deadline has passed, you no longer have the legal right to sue. In most states the statute of limitations for defamation actions is either one or two years from the date of defamation.

Comments

0 comment