views

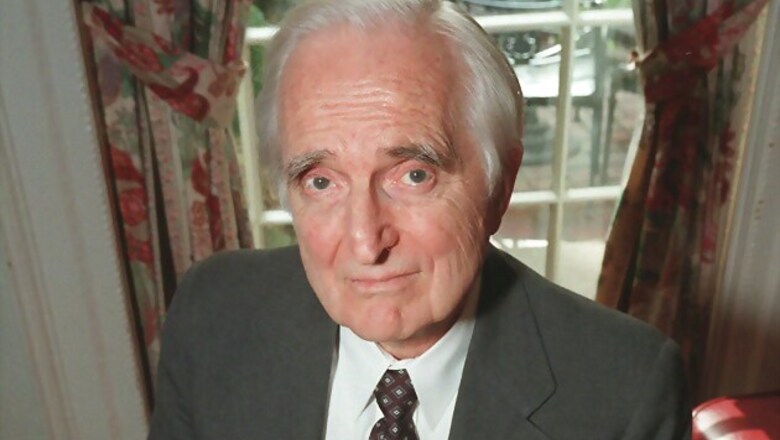

San Francisco: Doug Engelbart, the inventor of the computer mouse and developer of early incarnations of email, word processing programs and the Internet, has died at the age of 88.

The Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, where Engelbart had been a fellow since 2005, said Wednesday that it was notified of the death in an email from his daughter, Christina. The Stanford Research Institute, where he used to work, also confirmed his death. The cause of death wasn't immediately known.

Back in the 1950s and '60s, when mainframes took up entire rooms and were fed data on punch cards, Engelbart already was envisioning a world in which people used computers to share ideas about solving problems.

He said his work was all about "augmenting human intellect," but it boiled down to making computers user-friendly. One of the biggest advances was the mouse, which he developed in the 1960s and patented in 1970. At the time, it was a wooden shell covering two metal wheels: an "X-Y position indicator for a display system."

The notion of operating the inside of a computer with a tool on the outside was way ahead of its time. The mouse wasn't commercially available until 1984, with Apple's new Macintosh.

In fact, Engelbart's invention was so early that he and his colleagues didn't profit much from it. The mouse patent had a 17-year life span, and in 1987 the technology fell into the public domain - meaning Engelbart couldn't collect royalties on the mouse when it was in its widest use. At least 1 billion have been sold since the mid-1980s.

Among Engelbart's other key developments in computing, along with his colleagues at the Stanford institute and his own lab, the Augmentation Research Center, was the use of multiple windows. Engelbart's lab also helped develop ARPANet, the government research network that led to the Internet.

Engelbart dazzled the industry at a San Francisco computer conference in 1968. Working from his house with a homemade modem, he used his lab's elaborate new online system to illustrate his ideas to the audience, while his staff linked in from the lab. It was the first public demonstration of the mouse and video teleconferencing, and it prompted a standing ovation.

"Doug pioneered network computing technologies when it was not popular to do so," Sun Microsystems' then-CEO, Scott McNealy, said in 1997.

Even so, the mild-mannered Engelbart gave deference to his colleagues and played down the importance of his inventions, stressing instead his bigger vision of using collaboration over computers to solve the world's problems.

"Many of those firsts came right out of the staff's innovations - even had to be explained to me before I could understand them," he said in a biography written by his daughter. "They deserve more recognition."

In 1997, Englebart won the most lucrative award for American inventors, the $500,000 Lemelson-MIT Prize. Three years later, President Bill Clinton bestowed Engelbart with the National Medal of Technology "for creating the foundations of personal computing."

Douglas Carl Engelbart was born Jan. 30, 1925, and grew up on a small farm near Portland, Ore. He studied electrical engineering at Oregon State University, taking two years off during World War II to serve as a Navy electronics and radar technician in the Philippines.

It was there that he read Vannevar Bush's "As We May Think" in a Red Cross library and was inspired by Bush's idea of a machine that would aid human cognition.

After the war, Engelbart worked as an electrical engineer for NASA's predecessor, NACA, at its Ames Laboratory. Restless, and dreaming of computers that could change the world, Engelbart left Ames to pursue his Ph.D. at University of California, Berkeley.

He earned his degree in 1955. But after joining the faculty, Engelbart was warned by a colleague that if he kept talking about his "wild ideas" he'd be an acting assistant professor forever. So he left for the research position at Stanford Research Institute, now SRI International.

In 1990, Engelbart started the Bootstrap Institute, which researches ways to advance collaboration on complex problems.

Comments

0 comment