views

There can be little doubt that Gujarat is India's dragon state. The past decade has been the best since Gujarat became a state in 1960. Average annual economic growth, at 10.5 per cent, is two and a half percentage points higher than that of the nation. Achievement on the industrial front is to be expected: Gujarat is India's workshop along with Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. The surprise is Gujarat's agriculture. At 12 per cent a year, it has clocked to a Chinese rhythm, while the whole of India struggles to tick past the target rate of 4 per cent. All this has made the Gujarati richer than the average Indian by about a third.

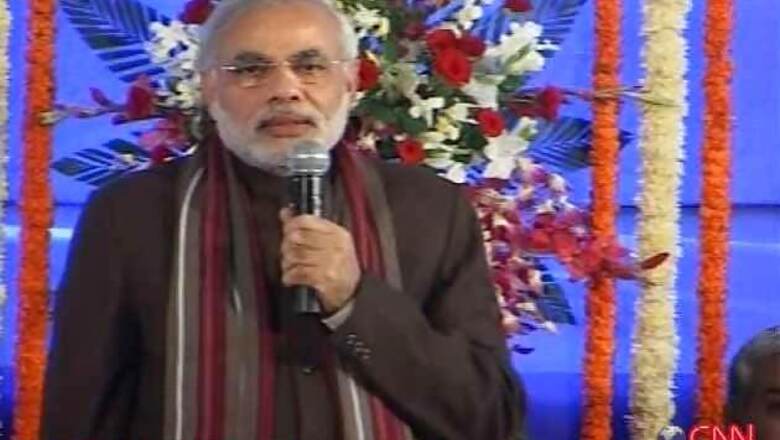

Gujarat has had 14 chief ministers. Narendra Modi is the longest serving – since 2001. As the past decade coincides with his tenure, he deserves much of the applause. Industry leaders hail him as the Prime Minister India never had. Such encomiums grate on those who see India as a vibrant and compassionate society, not just a thriving economy. Gujarat reflects in abundant measure the 'Beijing Consensus', which the Economist described as 'going capitalist, staying authoritarian'. Gujarat is the wrong place to look for social justice. It has been a schizophrenic society. The rage that burst through the fissures in 2002 was long seething. That explains why a Muslim mob could so readily set fire to a train with fanatical Hindu political volunteers on board and the bestial retaliation against Muslims that followed, probably with state complicity.

While Gujarat's politics is certainly not a template, there is much that the rest of India can learn from its economic model, allowing for certain unique factors. With 1,600 km of coastline Gujarat has long been a mercantile state. Being at the intersection of the Silk and Spice routes, it has a tradition of enterprise. Surat was India's principal port till the British shifted their affection to Bombay. This is where the East India Company's flagship Hector dropped anchor in 1608. Gujarat has a progressive administration, in part a legacy of the British. The princely state of Baroda was equally forward-looking and laid the base for the state's chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

Administrators like V G Patel and former union commerce minister Manubhai Shah encouraged start-ups by setting up institutes for entrepreneurship training and for providing venture capital funding, even braving disapproval from the Reserve Bank of India. Learning from China's special economic zones (like Shenzhen), Gujarat allowed development of ports – private and with the state as partner, in the 1990s. A chief minister like Chimanbhai Patel, notorious for corruption, was a practitioner of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping's practical philosophy of judging a cat by its catch, not colour. Nikhil Gandhi, the founder of Pipavav port (now operated by AP Moller-Maersk) recalls Patel telling his finance secretary to 'in a bania state, think like a bania,' when the official objected to taking a greenhorn like Gandhi, with no previous experience, as a port partner. Gujarat would gain even if Gandhi gave up midway, Patel reasoned; it could complete the project and get a port for half the price.

Modi therefore had a solid base upon which to build when he assumed office He has also been very lucky. There have been a string of good monsoons during his tenure, which is significant for a semi-arid state with a history of uneven and erratic rainfall: dry spells pulled agricultural growth into negative territory in almost half of the preceding 40 years. And even as Modi assumed office, India approved the use of genetically modified cottonseeds for commercial cultivation. From being an importer, Bt cotton has made India the second largest producer and exporter of cotton; Gujarat accounts for a third of the country's output, most of which is genetically tweaked.

But Modi is also an unabashed liberaliser. When attacked for his port privatisation policy, Modi is said to have remarked that 'the people of Gujarat are very enterprising and they want minimum government'. Some of Gujarat's minor ports (as state-domain ports are called) handle more cargo that major ports (owned by the central government), so much so that minor ports are now called non-major ports! Rising from the devastating earthquake of 2000 and leveraging its reserves of minerals, arid Kutch has attracted cement, steel, power and chemical industries. It is a global hub for pipeline manufacture. This is where the Adanis have set up a deepwater port with a large industrial enclave. Drinking water from the Narmada is now being supplied through a pipeline. Work on extending the Narmada canal for irrigation began last year. At one time people were fleeing Kutch. Now they are flocking to it. With 32 per cent growth over a decade, Kutch was the second fastest growing district in the state after Surat, according to the last population Census. It is a metaphor for Gujarat.

Modi can also claim part of the credit for the state's stellar growth in agriculture. A Supreme Court ruling early in the last decade allowing an increase in the height of the Narmada dam has helped. Modi's contribution is the 'Jyotirgram' program that assures farmers around eight hours of subsidised power at off-peak time for pumps though a separate Rs 1,200 crore electricity grid. Power rationing also conserves groundwater. This has by and large spared rural homes from power cuts, which were frequent when pumps were hooked to the same network.

A vigorous check dam movement provides insurance against weather shocks. This was a fall-out of nasty droughts in the 1980s and 1990s. Social workers provided the impetus. Village folk, who had made it big in Surat's diamond industry, sponsored the movement and spread the message, memorably though a 300-km mass march across Saurashtra. As chief minister Chimanbhai Patel gave official support. Modi has put the programme on skates by cutting red tape and providing technological support like satellite images to locate the water soaks. He is also keen on converting farmers to drip irrigation. A focus on outcomes, rather than on outlays, decided against housing the scheme in a government department. The Gujarat Green Revolution Company claims considerable success, though figures are not in the public domain.

Similar success is claimed for a five-year Rs 15,000 crore tribal development programme aimed at doubling household incomes among 15 per cent of the state's population living in hilly and forested areas. The touted gains from drought-resist hybrid corn seeds supplied by Monsanto and farm implements provided by John Deere to work the kerchief-size plots would need independent verification.

Modi has also fixed the agricultural extension system, which is broken in most states. Led by the chief minister himself and braving the May sun, tens of thousands of officials traverse the countryside testing soil, supplying high-yielding seed and exchanging information in a celebration of agricultural outreach during the so-called Krishi Mahotsav (farm festival). It is an exercise that other states should emulate.

Anyone who has travelled in Gujarat would vouch for its roads – only Tamil Nadu perhaps has a better network. The Word Bank, which financed the road-building programme, has compiled its happy experience in a book as a lesson for other states. Easier access to markets and suppliers has flattered both industrial and agricultural growth. Following the example of Malaysia, whose tourism industry piggy-backed on roads laid to promote industrial development, Gujarat is drawing in tourists who are persuaded to take a look in by Big B's catchy (kuch din Gujarat mein guzariye and Kutch nahin dekha toh kuchh nahin dekha) advertising campaign. M Thennarasan, the district collector of Kutch, says the 38-day festival at Dhordo in the salt encrusted Rann attracted 70,000 tourists last December, up from 32,000 in the year-ago month.

Gujarat's strengths in manufacturing have profited from Modi's salesmanship. Like former Andhra Pradesh chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu, he is an evangelist for industrial investment. The bi-annual Vibrant Gujarat melas are an occasion for Modi to flaunt his popularity among non-resident Gujaratis and to receive tributes in the form of investment pledges. Many of them do not materialise, but the commitments still add up to a lot. Since 1991, Gujarat has received $7 billion in foreign direct investment. It ranks fourth in FDI behind Mumbai and Delhi regions. What is significant is not where it is in FDI rankings, but where it has come from. In the 1990s, Gujarat was low down in the list. But it has climbed up the rungs despite not being known for IT and financial services (that get much of the FDI) and falling short of the frills of life: good schools, non-veg food and booze. Prohibition is official policy, though liquor is available for a price.

By slashing red tape, providing an administration that is said to be low on corruption, making land easily available, and assuring industrial peace (despite occasional strikes as at General Motors), Gujarat has attracted marquee industries. With Tata Motors, Peugeot, Maruti and Ford setting up plant or planning to, Ahmedabad has become an automobile hub like Mumbai-Nashik-Pune, Chennai and the national capital regions. Industrial enclaves, (known as Sirs, or special investment regions) to be set up along the new high-speed Delhi-Mumbai rail line for heavy goods trains, will add to Gujarat's manufacturing muscle. Transit-oriented development conducive to public transport could make the new cities models of low-energy urbanisation.

Modi's innovations in administration are also noteworthy. Administrators from the district collector down are encouraged to implement projects beyond their remit – the ambition of these programmes and the enthusiasm with which they are executed allows Modi to size them up. Feedback gathered through monthly grievance redress exercises over video links. An annual retreat brings chief minister and officials together for an exchange of experiences. Modi likes campaigns during elections and between them. There are campaigns to get the girl child in school, stop the killing of female foetuses, promote sanitation, provide nutrition supplements and encourage birthing in hospitals.

Some of these campaigns may be high on hype. During a week long tour of Saurashtra recently, I found the state buses in dire need of a wash (though they run on the hour and take you there). The bus depots were also filthy. Even a prime pilgrim centre like Dwarka had mounds of garbage. The road leading to Dholavira, the largest city in India of the 5,000-year-old Harappan civilisation, was deplorable. This experience is hard to reconcile with the claims made for the Nirmal Gujarat campaign launched in 2008.

Gujarat's health attainments are way below its level of prosperity. The death rate of infants (under one year) is the same as the national average. There is a yawning gap between rural and urban areas; the death rate being 51 and 30 (for every thousand born). The rate and disparity is much lower in states like Tamil Nadu (25 and 22). This does not mean that economic growth has been futile. Gujarat has reduced the infant death rate by 20 points over the last decade. But Tamil Nadu has done better with a reduction of 30 points.

But literacy is an area of cheer. The latest Census shows that the state has done better than the nation. It has also closed the gap with Tamil Nadu, and done much better than that state in rural literacy.

Even economic success must be tempered with caution. High growth in the farm sector bodes well for the state. The experience of Brazil and China shows that agricultural growth is two to three times more poverty reducing than growth in other sectors. But on the industrial front, Gujarat's growth is capital intensive, unlike Tamil Nadu, which leads the country in number of factories. A danger to watch out for is crony capitalism that can flourish under a charismatic and authoritarian leader who is convinced of his certitudes.

Last May I met Kanubhai Kalsaria, three times BJP MLA at his official house in Gandhinagar. Nineteen days after a 175-km walkathon from Bhavnagar to the state capital, he was nursing his sore feet with hot water fomentation. The protest was against Karsanbhai (Nirma) Patel's cement plant, which will lay waste to fertile fields and small industries like onion dehydrators and cotton gins that keep his constituents gainfully occupied. Kalsaria was telling Modi to put people first.

Gujarat is the last refuge of the Asiatic lion. The big cat sits at the top of the food chain.

In his zeal to attract large industries, Modi should not ignore those lower down in the pyramid. That would be a mistake like his failure to take all communities along.

Comments

0 comment