views

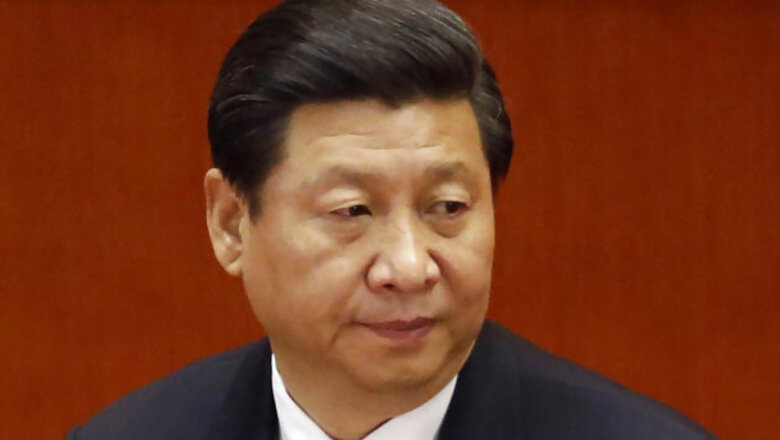

The visit of the Chinese President Xi Jiping provides an appropriate occasion for doing a reality check on what the supposedly 'peaceful rise of China' means for India; for it is in the climate of hope and excitement about India-China relations generated by such events that the counter-narrative of skepticism and apprehension assumes great importance.

Indians can sometimes be an incorrigibly optimistic people when it comes to matters of foreign policy; and we have been like this for centuries. And yet in the case of China, we have exceeded even our own very liberal hopes and expectations. Such, indeed, has been our optimism about this nation that even the treacherous humiliation of 1962 seems to have brought about only a partial change in our approach to China.

There are still some Indians, as well as foreigners, who look upon the 'peaceful rise of China' as its manifest destiny and a force for the good of humanity. Many Indians continue to have dreams of forging India-China solidarity in the name of third-world unity, developing-world unity, anti-American unity and myriad other causes for which Indians have been fighting for decades.

In fact, the rise of China could well represent the biggest threat to India and the world. The very nature of China as an authoritarian nation-state led by a closed Communist Party makes it a potentially disruptive force for India and the world. But this is not all. China's expansionist nationalism seeking to grab territories of its neighbors and its reluctance to play by international rules make its rise a matter of deep concern. The Chinese behavior with a host of countries in the last few years is a clear indication of the hubris and aggression that belie Chinese professions of a 'peaceful rise'.

Over the last 65 years, China has relentlessly pursued a policy of trying to circumscribe India because of its early assessment that a strong and unfettered India would be its most serious rival for power and status in Asia and beyond. The Indo-China War of 1962, China's all weather friendship with Pakistan, building of Karakoram highway through disputed territory, inroads in India's neighborhood, opposition to the NSG waiver for India, refusal to support India's bid for a permanent membership of the Security Council, and most importantly the recurrent forays into Indian territory in Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh - are all evidence of Chinese attempts at trying to 'contain' India in some South Asian sandbox.

India and China emerged as independent nations around the same time. However, while India's freedom struggle was largely a peaceful endeavor under Gandhi's guidance, China's Communist Revolution of 1949 entailed massive violence and upheaval. The leaders of modern China were all part of a long and violent struggle that culminated in the Communist takeover of 1949. It brought to power in China a Communist Party that ardently believed that violence was a very effective, and therefore legitimate, instrument for achieving desired national goals. Mao's assertion in a conversation with Nehru that he did not mind the loss of even one-third of his population in a nuclear war and Nehru's horror thereupon aptly sum up the different political cultures of the two countries.

The modern Chinese State at its very birth had a narrative of retribution and 'setting historical wrongs right' through violence. And what is more, it was at this very time the biggest potential threat for India from which it had to come to differ so much in terms of its political ethos. This is something that most Indian leaders at the time failed to read.

The misplaced idealism of India's leadership was obviously no match for the ruthlessness of Mao. India was a fledgling but confident nation in 1950s. The Chinese invasion of 1962 dealt a severe blow to our self-confidence at the time. We lost the war not because of any inherent weakness in us but because of the shenanigans of the Chinese leadership and our own woeful lack of preparations. As military conflicts go, the Indo-China war was no more than a minor affair. But it humiliated India, undermined our claims of third-world leadership, and seriously dented our image worldwide. And these certainly catered to Chinese objectives for launching the war.

To this day, China refuses to settle its borders with India. Obviously, it is biding time, waiting for the opportune moment when it can force India to agree to cede Arunachal Pradesh and Aksai Chin. Nothing else explains the fact that out of 14 neighbors India is among the only three countries with which China has not settled its borders.

And, let us be clear, in the long course of our history, China was never really a direct neighbor of India. Tibet had always existed as a massive buffer between the two countries, whose centers of civilizations were about 5,000 kms apart from each other. It is the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1951 that brought China to the borders of India.

Not only were India and China not immediate neighbors in history, their civilizations were never as similar to each other as it has been made out to be by some of our philosophers. The unity and solidarity of the 'Eastern Civilizations' was basically a modern idea whose genesis lay in the nationalist struggles against Western imperialism. Indian thinkers such as Tagore were among the chief proponents of this idea. Unfortunately, this idea gained too much traction among Indians, creating a general atmosphere of gullibility, credulousness, and complacency about China. In our enthusiasm for anti-imperialist unity, we unfortunately ignored key differences in the political culture and strategic aims between India and China.

India and China were always different from each other for three reasons. One, they were distinct civilizations; two, their dominant cultural spaces were quite far apart from each other without any common border at a time when the internet did not exist; and, three, China was in any case a relatively closed and isolated civilization, unlike India which was always open.

The export of Buddhism from India to China - which was perhaps their most significant interaction over the millennia - has not per se evolved into an enduring bond between the two civilizations.

India and China never had a common border. The McMahon Line was delineated not between India and China, as the latter believes, but between India and Tibet; the Chinese refusal to accept it is a classic case of making territorial claims on behalf of a territory unjustly occupied in the first place. There would perhaps be no other example in the modern world of such an irredentist, expansionist, and militaristic behavior.

As if this were not enough, over the last 50 years China has done everything possible to use Pakistan as a pawn against India including the supply of nuclear weapon designs and missile technology to Pakistan in clear violation of all international norms and treaties with the sole objective of keeping India tied down.

If this is not an act of enmity, what is, one wonders? China has in short, severely undermined the security of our nation by creating an ever-present danger of the use of nuclear weapons against India. Pakistan's strategy of 'bleeding India through a thousand cuts' is based on the nuclear deterrence that it has acquired mainly because of China with the United States looking the other way during the 1980s.

As against this, India has not done anything comparable. A comparable response to the Chinese act of nuclear proliferation would probably have been giving nuclear weapons to Vietnam or Taiwan. Yet India has never done this, banking upon shibboleths such as 'Asian solidarity'. The Chinese understand this; they know that India is different, and take full advantage of it.

It is obvious, therefore, that China is a country that has done a lot of damage to India's security environment in the last 60 years, and continues to do so despite pious professions of peace and friendship. It is thus that the emergence of China as a world power has made it an even bigger threat to India than it had been in the past, not so much because of any increase in Chinese belligerence and hostility to India, but because of an enormous increase in its ability to pose a threat to India.

One of the key weaknesses of India as a nation and of Indians as a people has been the inability to come to grips with the principles and practices of power. Most of us have scarcely any idea of what these entail in the relations between nations. We frequently have touchingly naive, morally-guided ideas about the role and dimensions of power on the world stage.

As wars go, India-China war of 1962 was not a very big affair. But it has left scars on the Indian psyche. It has also created certain fears in some Indian quarters of China's military might and its will to fight; and also now of its economic prowess.

All these fears are unfounded. And India must exorcise this deep-seated fear of China once for all. It is only after we have done this that India would be able to stand up to China, and command equal respect, which it unquestionably deserves.

The vast territorial expanse of China needs to be understood in the right perspective. The southern and eastern parts of China which constitute its core and where around 90 percent of its population is located is less than 40 percent of its total size of 9.5 million square kms. This is not vastly more than the total area of India. In any case, the physical size of a country is rarely a barrier to its becoming a great power. The example of England, a small island of no more than 5 million people in 1500, conquering and ruling over 25 percent of the world for more than a century provides ample evidence of this axiom.

The sorry spectacle of the PLA forces entering into our territory at will and our clearly inadequate response is a potent reminder of the threat that China poses to us. Not that it should prompt us into conflict. What it must do, however, is to egg us on to build our own military, economic, and technological might quicker than ever before.

The threat that China poses to India has of course been recognized by many of our leaders. Vajpayee's 1998 letter to Clinton justifying the Pokharan 2 by citing the war of 1962 and the Chinese nuclear weapons was criticized and ridiculed by many in India, but it was clearly a frank articulation of India's strategic assessment vis a vis China. Indeed, India's nuclear weapons program was developed from the very beginning to create deterrence against China, and despite tremendous international pressure was kept going by successive governments in view of its great strategic importance.

India has to compete with China, whether we like it or not. We have to become equally powerful in all respects not because of any intention to cause conflict, but in order to maintain an honourable peace with China. The Chinese behavior since 2008 recession is highly instructive. Coming to the conclusion that the US was finished as a super power, China visibly increased its aggression against Japan, India, Vietnam, and even the US itself. In other words, it took off the mask of 'peaceful rise', and started showing its real face of aggression and expansionism.

As V. S. Naipaul, arguably the greatest living writer in the English language, has said in one of his finest books A Bend in the River, ' The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it'. So we Indians have to understand that the international rules of power will remain what they are. It is we who have to decide whether we want to be a weakling or a great power.

The point made here is not that we should not strive to have good relations with China. Of course, not. India must strengthen its economic cooperation with China, increase trade and investment, participate in institutions like the BRICS and the SCO, intensify cultural exchange, encourage the movement of Indian students to China and vice versa, and co-operate in the UN, WTO and other multilateral organizations whenever our national interest so requires. India must do all this.

What we must never do is to commit the mistake of imagining that these things by themselves would make China take us seriously or prevent its aggression towards us. What we must never do is to commit the mistake of taking the Chinese professions of friendship too seriously. Instead, we must follow Theodore Roosevelt's dictum, 'speak softly, and carry a big stick; you will go far'. When it comes to the crunch, it is only our national strength that would enable us to keep peace with China on honourable terms. And this peace is important for these two countries as well as for the world.

Ravi K. Mishra is a professional historian and a long-time observer of Asian affairs. He can be reached at [email protected]

Comments

0 comment