views

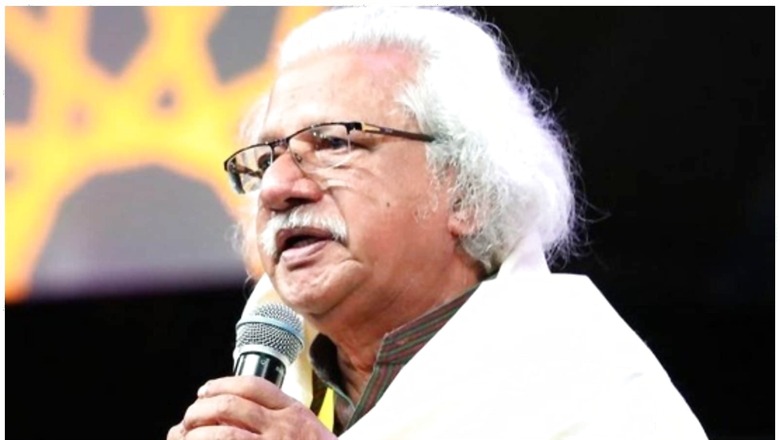

Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s first film, Swayamvaram or One’s Own Choice, turns 50 this year – having opened in 1972. And it had several firsts to it credit – Adoor’s to be very precise. The movie in Malayalam stormed Kerala’s conservative citadels with its extremely radical story, outdoor locations and synchronised sound. All unheard of in Kerala of the 1970s.

Adoor used his Nagra recorder, carted his camera beyond the studio walls to tell us the story of Viswanathan and Sita, who defy parental wish, elope to a city to live together outside marriage. The plot created sensation after sensation, and its publicity campaign was just unique.

Gopalakrishnan’s artist friends spent days and nights at the Chitralekha Studio drawing and painting posters for the film. Cinema posters were usually designed in Chennai and printed at Sivakasi, a town in Tamil Nadu in southern India also renowned for match and fireworks industry, and, worse, child labour. But Swayamvaram’s posters were pure couture, each visualised, sketched and painted by an artiste.

After all this, the movie hardly ran for a week in most theatres. It was ignored, perhaps even jeered at, by the Kerala State Awards. But at the National Awards in New Delhi, it clinched the Swarna Kamal for Best Picture, and awards for Best Director, Best Cinematographer (Mankada Ravi Varma) and Best Actress (Sarada, who plays Sita).

There are two scenes Sarada would always remember. One was in a bus, the opening scene, where Adoor asked her to be just another ordinary passenger. To look and behave as real people did in real buses, and for her, it took some courage and effort to do that. There was another scene where a pregnant Sita carries a pot of water, and “Adoor asked me not to dramatise this. Your expression should only say this much and not more”. There was no scope for melodrama in his cinema.

In fact, the film has a series of such naturals. Viswanathan (actor Madhu) brushing his teeth, Sita picking up a bed-sheet and dropping it on the ground, a little boy sent on an errand, steering an imaginary car, prostitute Kalyani’s (K.P.A.C Lalitha) easy charm with smuggler Vasu (P. Venukuttan Nair) and her mocking tolerance as he appears smitten by Sita are some scenes that could have been lifted from the life we see every day – and all around us.

Swayamvaram is perhaps Adoor’s most conventional narrative. Its structure is simple and straightforward. The story opens with the couple, who have decided to run away and live together without the sanctity of marriage – in defiance of parental wish and societal norm, though in a weak moment Sita asks Viswanathan to get her a “mangal-sutra” — only to stop idle gossip.

The movie’s first scene is a long one in a bus – which brings them to the city – the journey acting as a harbinger of the days to come when Viswanathan and Sita would face disturbing uncertainty. Their life would be rocked, and their inability and helplessness to find peace and permanence outside matrimony and the comfort of their parental homes form the basis of this insecurity. There are other factors precipitating this.

Viswanathan dreams of being a writer, which he hopes would help him earn money to keep his home fire burning. He goes to the publisher of a magazine to get his novel serialised. An initial encouragement from the publisher does not fructify, and Viswanathan has to opt for teaching zoology in a private tutorial college, whose principal (Thikkurissi Sukumaran Nair), heavily in debt, is unable to pay him his salary or even retain him beyond a short time.

Optimism turns into pessimism, and the trial of the young couple seems cruel. They have to move into very modest lodgings, where Kalyani is their neighbour. A by then pregnant Sita — harassed by their landlord and sometimes Kalyani’s prospective clients, including Vasu — is at her wit’s end, when Viswanathan is hired as a clerk in a sawmill, where he is accosted by a dismissed employee (Gopi). Viswanathan is troubled by the fact that his own placement has robbed someone else of his job.

Sita is uncomfortable pretending to be a married woman, but is not bold enough to say she is not, while across her street a married Kalyani cares little about community, eking her livelihood by prostituting, having a boyfriend in Vasu and treating her husband, who comes to her begging for money to get his next fix, like a piece of dirt.

Finally, when Viswanathan, weighed down by the guilt of not being a good provider, succumbs to fever, Sita faces yet another dilemma of making a choice. Virtually penniless and with a child to feed as well, she may return to her parents or become another Kalyani. However, what is imperative here is her freedom to choose, a freedom she also exercises in the beginning, that to live with Viswanathan without marrying him.

Exceptionally photographed by Mankada Ravi Varma – who was with Gopalakrishnan till Nizhalkkuthu in 2002, marking a 30-year association that ended only because the cinematographer fell ill – the film uses powerful visuals over words to tell us a love story. And beyond this lies Gopalakrishnan’s perennial concerns about unemployment, political extremism and the freedom, or lack of it, to make personal choices that he addresses through Viswanathan and the retrenched employee as well as Sita and Kalyani. In some ways, the story – some call it a Shakespearean tragedy, though it is not as classic — serves to underline and highlight disturbing social issues.

If one were to look a little beyond the characters and into the frames, one would easily find a strong indictment of the 1970s Kerala: people had grown weary of Nehruvian idealism and Marxist ideology. This message stares in our face as poignantly as the retrenched worker’s silent gaze into Viswanathan’s eyes. We realise then the failure of Marxism, and are disillusioned with Nehru’s thought.

Gopalakrishnan exposes the angst of the Kerala community – transiting from a middle class mindset to modernism – through the pain of the young couple. Banal values are yielding to romance and money, and decision-making is no longer with the collective. Rather, it is with the individual. Sita’s and Viswanathan’s, for example.

Swayamvaram has an open-ended story. We do not know what happens to Sita, and this makes the work all more brilliant.

(Borrowed liberally from my biography of Adoor Gopalakrishnan — A Life in Cinema)

Read all the Latest Movies News here

Comments

0 comment