views

After decades of dwindling numbers, India’s tigers are roaring again. There are now at least 3,167 striped cats in the country’s forests, announced by the government in one of its biggest wildlife surveys ever – that spanned over four years and 20 states.

But as the estimates point towards a rising trend – the falling number of the endangered cat in critical biodiversity hotspots have set the alarm bells ringing.

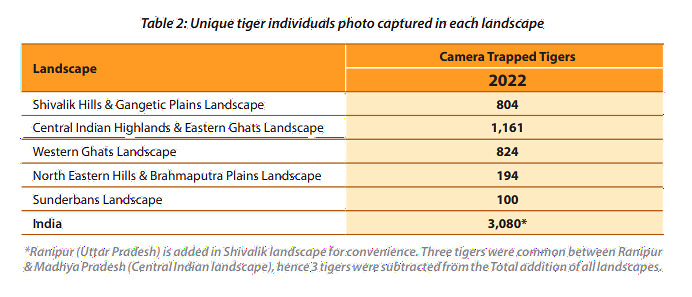

Barring a few areas, tiger occupancy has “decreased significantly” throughout the Western Ghats, including the Nilgiri biosphere landscape which is home to the world’s largest tiger population. Only 824 unique tigers were recorded in the region, compared to nearly 981 which were estimated in the previous survey conducted in 2018 – a fall of 157.

While the populations within the protected areas have remained somewhat stable, it is the tigers prowling outside of these well-protected regions which have taken a big hit. The number of big cats have decreased in Kerala’s Wayanad landscape, Karnataka’s BRT Hills, and the border regions of Goa and Karnataka.

UNSAFE OUTSIDE PROTECTED RESERVES

The forests are fast disappearing leading to more human-animal conflicts. There have been multiple reports of poisoning, snaring of tigers in human-dominated landscapes. India had lost as many as 551 tigers from 2018 to 2022. The average tiger deaths per year has hovered around 110 over the past five years, with 52 deaths in the last four months alone.

Even as the government expands the tiger habitats – locally translocating a new batch of animals to reserves where they go extinct – the animal remains at risk outside the fully-protected reserves. Out of at least 1,062 tiger deaths recorded over the last 10 years, 35.2% were outside the protected areas and an additional 11.5% were seizures, shows data from the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA).

This is likely to pose a big challenge, as reserves reach their carrying capacity but habitats outside shrink due to human encroachment. Out of the over 400,000 sq km of forests in tiger states, only one-third are now in are relatively healthier condition.

EXTINCTION WITHIN RESERVES

The small population of tigers within the isolated reserves too are imperilled. The report threw light on how the local tiger population has become extinct in several areas, Sri Venkateswara National Park, including Tiger Reserves like Kawal (Telangana), Satkosia (Odisha) and Sahyadri (Maharashtra). A major decline in tiger occupancy has been observed in the Mookambika-Sharavathi-Sirsi landscape. Local extinctions of tiger populations have also been noticed in Tamil Nadu’s Kanyakumari, and Srivilliputhur regions.

The recovery of tigers in the Central Indian landscape also remains low, with “serious conservation efforts needed to retrieve their population in Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh, says the report.

Several tiger reserves still remain devoid of the carnivore in the North Eastern Hills and Brahmaputra region. Only 194 distinctive tigers were camera-trapped this time, compared to 219 estimated count in 2018. Even though poaching is illegal, the demand for tiger products remains high, and poachers continue to kill tigers for profit.

Another ecologically fragile region – the Sunderbans – recorded 100 tigers compared to 2018’s estimate of 88. The population is steady with a limited potential to extend its range largely because of the threats due to climate change which has left the region extremely vulnerable, says the report.

WHAT DO THE NUMBERS SAY?

The survey gives a minimum estimate of 3,167 – a number arrived at using data from camera-trapped space and further extrapolation in model-predicted space.

This means while the actual number of tigers individually confirmed through camera-traps is 3,080. But when extrapolated to regions where the camera traps were not placed using models, the number is likely to be 3,167. In 2018, the survey had photographed 2,461 unique tigers, which was fewer than this.

However, some experts say the numbers are inadequate to assess an overall trend, as the methodology has lacunae. “The report is still incomplete and a lot of analysis is still in progress. The numbers largely come from ‘model-based estimates’ and they have proven to be largely uncertain in the past,” says wildlife and statistical ecologist Dr Arjun Gopalaswamy.

The concerns also arise from the varying parameters in each of the previous cycles. Unlike 2018, the survey has brought a larger area under camera traps especially in Maharashtra. Camera traps were deployed at as many as 32,588 locations compared to just 26,838 in 2018 – resulting in 47 million photographs of which 97,399 were of tigers.

Read all the Latest India News here

Comments

0 comment