views

Losers don’t write history. History is written by those in power.

In 1948, soon after India gained Independence, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, India’s foremost historian, submitted a proposal to the government to write an “authentic” and “truthful” history of the freedom struggle. His proposal was duly accepted. And in 1952, the Ministry of Education appointed a Board of Editors under Majumdar, and the first volume of the series was published in no time. But in 1955, the board was dissolved. A year later, when the project was revived, Majumdar found himself removed and his place was given to a bureaucrat named Tara Chand.

Why was India’s foremost historian treated so disdainfully by the Nehruvian dispensation? Because in the first volume, he had shown the moral courage and intellectual integrity to call the Nehruvian bluff on Hindu-Muslim unity before the advent of the British. These two communities, he wrote, lived as “two separate communities with distinct cultures and different mental, and moral characteristics”. This line was contrary to the famed Nehruvian stand that saw the two communities living together in peace till the British pulled them apart with their divide and rule policy. But more importantly, Majumdar threatened to take the lid off the Nehruvian myth that India’s Independence was solely the handiwork of Mahatma Gandhi’s ahimsa and satyagraha.

Ironically, those in the thick of things just before Independence saw the entire episode differently. For them, Gandhi’s role in India’s freedom struggle was “m-i-n-i-m-a-l”, as then British Prime Minister Clement Attlee told Bengal’s acting governor Justice PB Chakraborty, slowly chewing out the word to make an instant, dramatic impact. According to him, the role played by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and his Indian National Army (INA) was paramount in the British leaving India.

Dr BR Ambedkar too reflected the same sentiment during his interview with BBC in 1955. “The British had been ruling the country in the firm belief that whatever may happen in the country or whatever the politicians do, they will never be able to change the loyalty of soldiers. That was one prop on which they were carrying on the administration. And that was completely dashed to pieces (post INA and 1946 Royal Indian Navy uprising). They found that soldiers could be seduced to form a party — a battalion to blow off the British,” Ambedkar said.

Interestingly, the Congress, which did everything to wipe out the memory of Netaji Bose post-Independence, was in the forefront in 1946, as per The New York Times, “to build up Bose as the George Washington of India”. The party, after seeing the massive public support for the INA, also took up its trial case — but after coming to power the same party removed all INA men from the services and even put some of them on trial. Bose became untouchable overnight. He was not to be invoked, remembered and, worse, celebrated. When HV Kamath, a member of the Constituent Assembly, sought a portrait of Netaji Bose to be installed at the august house, he was snubbed! Such was the antagonism for Bose that the Nehru dispensation snooped and spied upon his family members.

Bose wasn’t the only revolutionary to be targeted and abused. After sidelining the likes of RC Majumdar and Sir Jadunath Sarkar, the government got in their place a set of pliant historians who would push the Nehruvian agenda without any question. These new historians worked overtime to oppose, vilify and even demean anyone and everyone they thought would threaten to take the shine off the Gandhi-Nehru duo. In this endeavour, even Left-leaning revolutionaries were not spared. No wonder, Bipan Chandra, in India’s Struggle for Independence, regarded Bhagat Singh and his ilk as “revolutionary terrorists”. In Modern India, Prof Sumit Sarkar, another eminent historian, uses the term “terrorists” or “Bengal terrorists” for Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki. Very recently too, Sunil Khilnani, in his latest book, Incarnations, calls VD Savarkar “the young terrorist”!

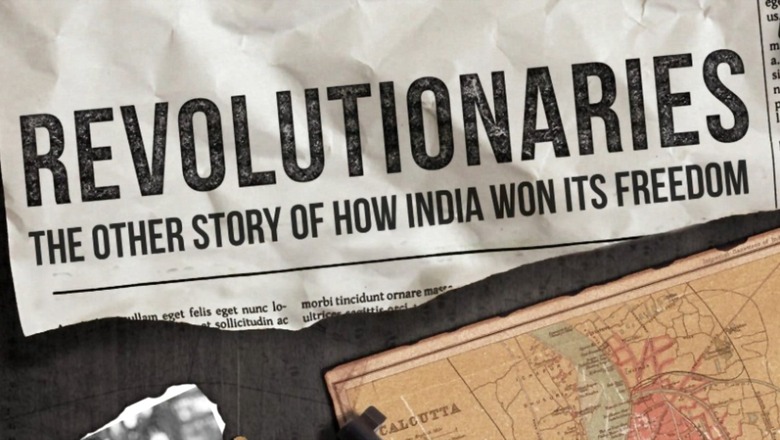

It is in this backdrop that Sanjeev Sanyal’s book, Revolutionaries: The Other Side of How India Won Its Independence, must be acknowledged and appreciated. For, as the title of the book suggests, it aims to correct the most fundamental distortion in the history of India’s Independence: That Gandhi’s ahimsa and satyagraha alone got India its freedom. The fact is that the revolutionaries played an equally important, if not bigger, role in this endeavour.

According to Sanyal, India’s revolutionary movement wasn’t the case of marginal, episodic and isolated heroism, more often than not misplaced in its priorities, but a well-organised phenomenon that worked incessantly for India’s Independence and which had well-organised international networks and dimensions with “nodes in Britain, France, Thailand, Germany, Russia, Italy, Persia (now Iran), Ireland, the USA, Japan and Singapore”. He writes, “This (revolutionary movement) was no small-scale movement of native individual heroism but one that involved a large number of extraordinary young men and women who were connected in multiple ways to each other and to evolving events of their times.”

Indian revolutionaries were as much influenced by foreign revolutionaries, especially Mazzini and Garibaldi, as they were by indigenous heroes such as Rana Pratap, Guru Gobind Singh, Banda Bahadur, and Shivaji. Among all, Shivaji holds special relevance for these revolutionaries. “His (Shivaji’s) guerrilla tactics against overwhelmingly stronger enemies and his daring escape from Emperor Aurangzeb’s clutches were an obvious inspiration for revolutionaries, who saw themselves in very similar circumstances,” Sanyal writes.

The book begins with the exploits of the Chapekar brothers who, as per some writers, “marked the beginning of the revolutionary movement in India”. Sanyal, however, believes that the three brothers were “certainly influenced by the political forces unleashed by Tilak, but they were neither members of a significant network, nor did they have any long-term political objectives”.

The book, then, in different chapters, talks about the exploits of Sri Aurobindo, Veer Savarkar, Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekhar Azad, among others, ending finally with Subhas Chandra Bose. The central theme following these stories has not just been how the revolutionary activities have played a prominent role in India’s Independence, but also how they were well-connected and organised.

The high point of the book, however, is the saga of Sachindra Nath Sanyal and Maharaja Sayajirao III. Today, very few would know, and even fewer would care to know, that Sachindra Sanyal was the only revolutionary who was sentenced twice for Kalapani. Sachindra Sanyal was sent to the Andamans twice — once for Ghadar (released in post-Jallianwala amnesty) and the second time for the Kakori conspiracy case. He had had an intuition in the 1920s that the history of the revolutionary movement would be deliberately sidelined. In the preface of his book, Bandi Jeevan (A Life in Prison), he writes that the reason for his writing the book was not merely to inspire contemporary revolutionaries but also to leave behind a personal testimony for future generations. “I am writing this book so that in the future a few chapters of Indian history can be correctly written,” Sachindra Sanyal observes.

Sachindra Sanyal had his reasons for being so uncertain about the fate of the revolutionaries. In the 1920s, he reached out to the young emerging leaders of the Congress. He was impressed by Subhas Bose, but he seemed to have found Jawaharlal Nehru “too haughty”. In Bandi Jeevan, he writes, “While I was talking to Jawaharlal-ji, his attitude was that he was indulging a feeble-minded simpleton and was graciously wasting his precious time by listening to his foolish ideas.”

Maharaja Sayajirao III’s story too explains why the revolutionaries found themselves sidelined post-Independence. Sayajirao, who provided generous financial support to several talented Indians of his time, including Ambedkar and Aurobindo Ghosh, often “sailed close to the wind”. During the 1911 Delhi Durbar, Sayaji broke the royal convention by not just refusing to wear the full regalia, but also making just a single perfunctory bow, instead of the customary three. Thereafter, he turned around and walked off, showing his back to Emperor George V — much against the royal convention.

Eyewitnesses suggest that Sayaji was laughing mockingly as he walked away from the throne. This single act of defiance should have made him the hero of free-spirited Indians, but Motilal Nehru, who was one of the witnesses to the event, saw it differently. He wrote quite disapprovingly to his son Jawaharlal, “I am sorry to say that the Gaekwad had fallen from the high pedestal he once occupied in public estimation.”

Unfortunately, as foreseen by Sachindra Sanyal, while the revolutionaries freed the country from the British yoke, post-Independence they lost the political battle to the Nehruvians. Revolutionaries fought for freedom very hard, but when it came to power-sharing negotiations with the British, there was no one left from their side to do the talking. The last of their giants, Subhas Bose, was mysteriously missing after World War II. The vacuum was misappropriated by the Nehruvians to their petty advantage.

History, indeed, is written by those in power! Sanjeev Sanyal deserves applause for putting the much-needed light on “the other story” of how India won its Independence.

The author is Opinion Editor, Firstpost and News18. He tweets from @Utpal_Kumar1. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment