views

Taken in context, China brokering a truce/peace between Saudi Arabia and Tehran may impact wider political geography, including India. If nothing else, it may ensure that much of West Asia/Middle East proclaims neutrality in any future geopolitical standoff between China and the US, and also between China and India. It may not be good from a historic Indian socio-political perspective, whatever be the geo-strategic benefits accruing from the relatively recent geostrategic overtures between India and the US, whose limitations the Ukraine War has already exposed.

Going beyond the provocative American behaviour over the ‘Khashoggi affair’ in 2018, China’s twin Saudi-centric initiatives were waiting to happen. Unlike the US and its Western allies, China does not concern itself with human rights issues in third nations. Over the past decades, Gulf-Arab sheikdoms have been perturbed by the region-wide fallouts of the anti-establishment ‘Iranian Revolution’ of 1979-80.

To them all, the Taliban and the Al-Qaeda combo in Afghanistan and then Pakistan, both before and after 9/11, were unwelcome. Even more so was the ‘Arab Spring’ kind of ‘orchestrated’ anti-establishment mass protests, where they saw a hidden American hand, for instance, in the dehumanised death of Libya’s Gaddafi. In between, the second American war against the purported ‘Axis of Evil’ on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in the name of non-existent weapons of mass destruction (WMD) opened their eyes to possibilities. They needed a new ally in the new century/millennia, and China with its non-interference political policy and mutually supportive economic outreach suits them fine. Like the US in the Cold War era, but not anymore, China sees it all as a political investment for the future.

From a Chinese perspective, Beijing might have neutralised the overwhelming US presence in inter- and intra- Gulf policy, without actually expecting them to take its side in any future face-off with the US. Though still dependent on the US in the UN fora, Israel, on the other side of the Gulf’s socio-political gulf, too has been striking it on its own for a few years now.

West Asia, starting with long-time friends, allies and strategic partners of the US has sent out a message that the US cannot take them for granted anymore. Through long years of association, the US has taught them the term and meaning of ‘supreme national self-interest’. India, a quick learner of American political idioms, has taught them through its Russia policy on the Ukraine War. China, too, took the same line but it had little choice.

As if not to lose time after deciding to resume bilateral relations, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud of Saudi Arabia has invited Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi to visit Riyadh. Raisi, according to Iranian reports, has accepted the invitation. The visit, when it takes place, has the potential to rewrite political equations all across West Asia/Middle East. It may evolve a contemporary dynamic of its own, where China, at times, might be made to feel like an ‘outsider’ as much as the US from now on. Of course, Israel may be concerned even as other regional nations like Egypt are maintaining silence.

Two ‘coups’ in four months

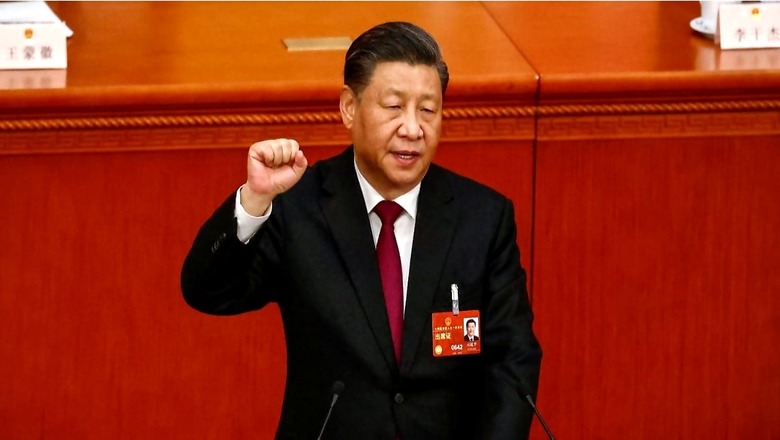

For China, it is two Saudi-centric diplomatic coups in four months. In December, Riyadh hosted and facilitated President Xi Jinping getting a foothold in the 22-member Arab League. He has since given himself a third-term inauguration gift in March by getting Saudi Arabia and Iran to restore diplomatic ties after a six-year break. US President Joe Biden had the opportunity to do it, but he toed Republican predecessor Donald Trump’s antagonistic approach to Iran, rather than his former Democratic boss, Barack Obama, who sought to set things right on the bilateral plane but could not complete the process.

The more the US has been painting China as the aggressor in Taiwan, the slower Beijing has been to bite the bait. When the US sent former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan, offering a strategic distraction from the war in Europe and following it up by sending a naval vessel to those waters, China did not react as much. Nor did it wholly side with Russia in the European war. A stage soon came when the US charges of China supplying weapons to Russia needed independent corroboration, which, however, was not coming even from America’s western/West European allies.

The US has over 30 military bases in the Gulf-Arab region, including five in Saudi Arabia. No one is suggesting that they all would ask the US to shut them down, here and now. They may, however, tell Washington not to deploy American forces from those bases against nations friendly to them, say, Iran in the changed environment. As may be recalled, the US had used bases in Gulf Arab bases during the anti-Iraq ‘Kuwait War’ in 1991. Unlike in the past, it may have to be wary about domestic street interpretation or any such military initiative as ‘war on Islam’.

Less dependent on oil

China’s future moves in West Asia would be keenly watched. While dealing with Saudi Arabia and Iran at the same time, Beijing is also dealing with the 57-member Organisation of Islamic Countries (OIC), spread across continents, and the 22-state Arab League, confined in the Gulf region. The membership of the two is intertwined.

Then, there is the 55-member African Union (AU), where, too, the other two have their own relevance and influence. Between them, the OIC and the AU are the largest blocs in the UN General Assembly (UNGA). They are not together on all matters, but with China staying in the background, the scenario may change over time, based on issues. That alone may also be China’s ambitious goal in the first stage.

For India, over the past couple of years, ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) social media activists have been claiming that under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the nation’s relationship has flourished as never before, and not certainly under Nehruvian Congress leaders, as often propagated. It is now becoming clear that such a Gulf-Arab outreach to India was a part of the larger picture and not a standalone affair.

It was a fair assessment, but only up to a point. Even after the Saudi patch-up under China’s watchful eyes, Tehran has sought the resumption of oil imports from the country, citing difficulties in procuring the same from Russia, through Western sanctions. It may be Iran’s way of testing the strength of bilateral relations, and India’s willingness to take lesser risks on the sanctions-cum-import front compared to Russia’s.

However, the pro-Modi social activists in the country should understand that under new leaderships, especially the ‘moderniser’ in Saudi Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman Al Saud, or MBS for short, the region is re-positioning itself for a world less dependent on oil and whose production too could begin reducing drastically for them to use it as a political tool. The US military presence would not serve them much, either. They seem to be falling upon the old dictum of making up with enemies than surrendering to supporters.

Traditional friends

From an Indian perspective, this in turn means that its traditional friends in West Asia could move closer to the centre in matters involving China, or the US and the rest of the West. The positive side, for now, is that they are not as much concerned about the Pakistani ranting on the ‘Kashmir issue’ as they used to be in solidarity with a fellow Islamic nation. In this era, after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, some of them may begin to see Pakistan as less of an Islamic nation and more of a South Asian country, all over again.

Such thinking on their part could well be replaced by individual nations and groups taking a closer look at India on religious issues than earlier. In establishing ties with China, the ‘Uyghur crisis’ has not hurt them. But such comparisons need not apply to India’s case all the time, as they would pick and choose issues, depending on the existing and evolving public mood near home. When it is human rights, they may find themselves on the same page as the US-led West vis-a-vis India, but not necessarily in the case of China.

Larger scenario

For India, West Asia is a major trading and investment partner. Until

Russia’s offer of cheaper oil, Saudi Arabia used to top the nation’s oil source. As of 2020, the region also hosted 7.6 million labour from the country, more than half the total of 13.6 million NRIs. There are reasons to believe that the numbers would have only increased, and so would the NRI remittances from the region as a whole. All this comes with a tag for New Delhi as shown by past evacuations at the height of the ‘Kuwait War’ (1990), Covid pandemic (‘Operation Vande Bharat’, 2021) and the Ukraine War (‘Operation Ganga’, 2022), among others.

In all this, there is a larger scenario that neither India nor the rest of the world can overlook. From Myanmar and China in the East, through Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran and Russia, not excluding West Asia now, more and more nations can now take a neutral stand in matters with India and China, and also India and Pakistan, as against their tacit or open support for the nation.

It is not as if many of them had backed India outright in the past, but many, if not most of them, had definitely identified with the US, New Delhi’s post-Cold War strategic partner. It would have worked for India in times of need. New Delhi also has to keep a closer watch on US-European relations, both during the Ukraine War and in the post-war years, whenever. Nations like France and Germany were known to be wanting to strike roots independent of the US in geo-strategic affairs (hence their own Indo-Pacific strategies) but they were unable to carry the EU’s poor member-nations with them.

How India’s new-found aggression viz Western Europe plays out too remains to be seen after External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar ticked them off on ‘Europe’s problems are not the world’s problem’. If the reference was not to the colonial past or the two World Wars of the previous century, the Ukraine War has still shown that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems.

Whatever China’s prescriptions for the Saudi-Iranian patch-up, if it works, Xi may now turn his attention to try ending the Ukraine War, where he has an open invitation from President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, as if his nation was tired of fighting somebody else’s war more than its own. Even if he succeeds halfway, the temptation for Xi to turn his attention to the intractable ‘Kashmir issue’ should not be underestimated.

For some decades before Doklam (2017) and Galwan (2020), through Track 2, China, using Aksai Chin in its possession as a lever, was mooting a three-way conversation with India and Pakistan. New Delhi is still wedded to a bilateral approach to Pakistan under the ‘Shimla Agreement’ (1972) and there has not been any suggestion to the contrary.

If the US sees a distant Chinese hand, it is bound to push for a one-on-one India-Pakistan rapprochement, which does not look possible just now but is still the only way out, barring a decisive war. Pakistan’s economic ills, coupled with greater American realisation that it now badly needs a foothold in extended West Asia may tempt it, even more, to look at the options.

The recent bi-partisan resolution in the US Senate, asserting the acceptance of McMahon Line and Arunachal Pradesh as an integral part of India may be aimed at snubbing China, which has been amassing troops along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with India. But it may also open up negative arguments as to what the US thought Arunachal Pradesh, otherwise, was, all through.

The writer is a Chennai-based policy analyst & political commentator. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment