views

The state of income in India has suddenly become a topic of raging discussion after former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan and economist Rohit Lamba suggested that the country cannot escape the lower-middle income trap by 2047. The pessimism seems hasty, as data and a series of studies estimate that India’s progression into at least a middle-income nation is inevitable by 2047. Certainly, the growth momentum must be sustained and even pushed further to achieve that goal. However, to paint a hopeless picture is certainly not the right approach, since statistics show the fortunes of Indians are changing for the better, and changing fast.

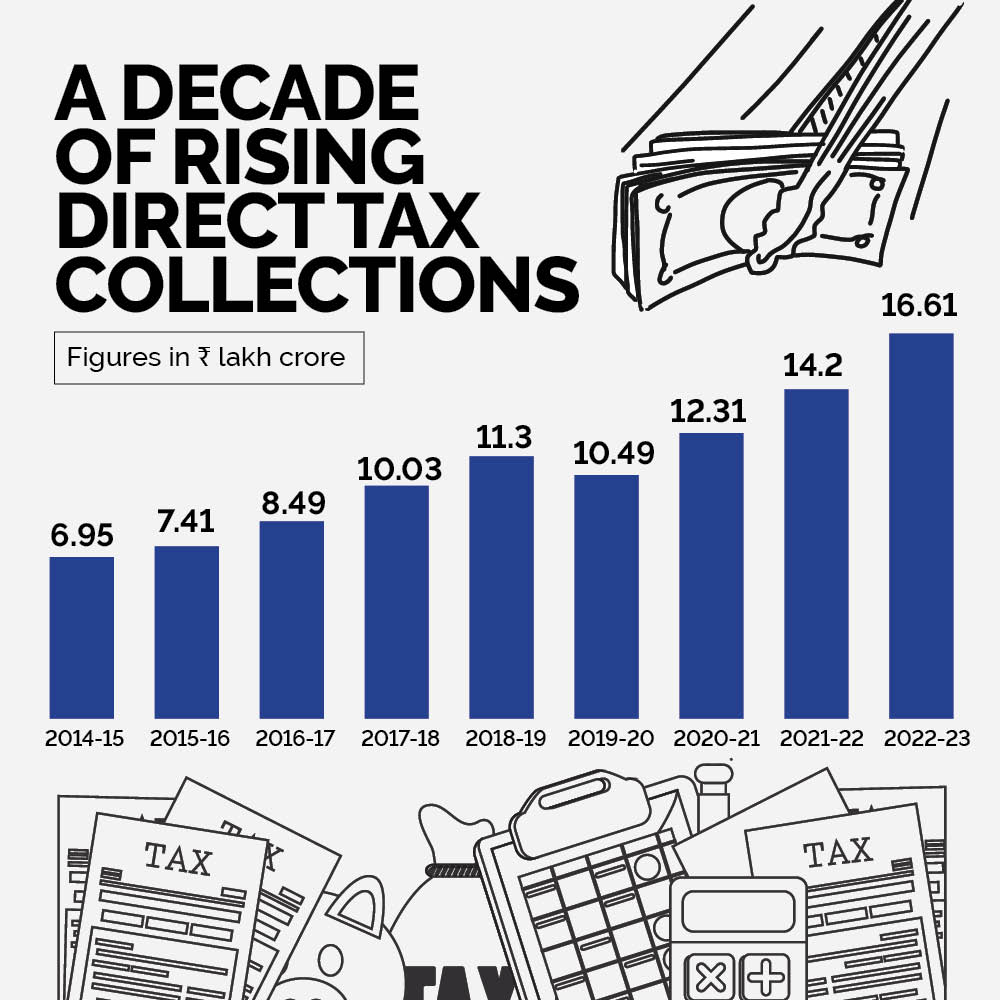

Let’s start with the basics. As PM Modi pointed out earlier this year, per capita income has doubled since 2014-15. More and more Indians are paying income tax every year, as is evident not just from the rising collections of the government, but also from the number of people filing their returns. India’s gross direct tax collections in the ongoing financial year, until November 9, have increased almost 18 per cent to Rs 12.37 lakh crore. Meanwhile, the net direct tax collections (after issuance of refunds) amounted to Rs. 10.6 lakh crore between April and November 2023, representing an increase of 23.4 per cent from the corresponding period in the last fiscal.

At the same time, advance tax collections up to the third quarter (April-December) of FY24 are up 19.8 per cent from a year earlier and have reached Rs 6.24 lakh crore. It is estimated that the total direct tax collection in FY 23-24 will comfortably cross the Rs 18 lakh crore mark – signalling a remarkable expansion of the country’s taxpayer base, and also how much this base is contributing to the government’s kitty.

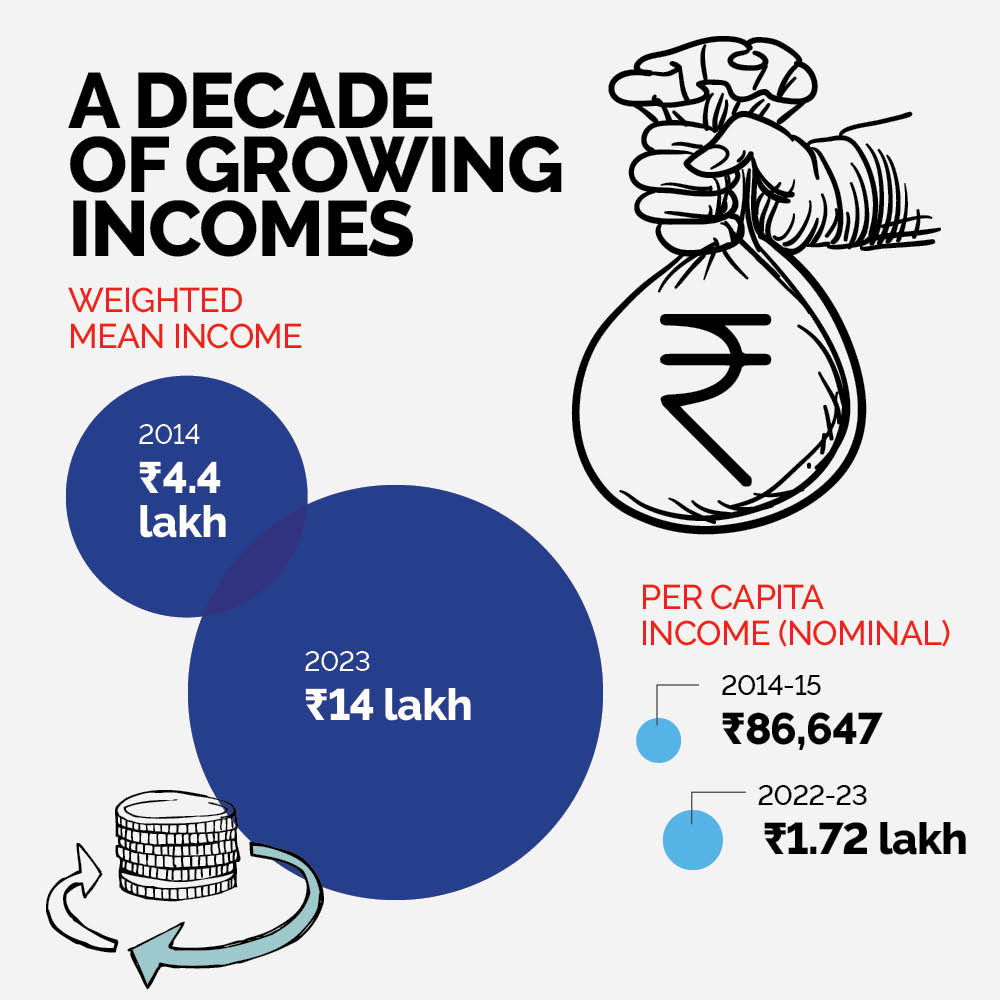

Let’s take a look at what more income-specific data has to say. According to a research report by the State Bank of India, the weighted mean income in India rose from Rs 4.4 lakh in 2014 to Rs 13 lakh in FY23. In the same period, India’s per capita income in nominal terms almost doubled to Rs 1.72 lakh in 2022-23 as compared to Rs 86,647 in 2014-15.

Analysis of data released by the Income Tax Department in October shows that between 2011-12 and 2020-21, there was a 20 per cent average annual growth of those earning between Rs 5.5 lakh and 25 lakh a year – which is a five-fold hike.

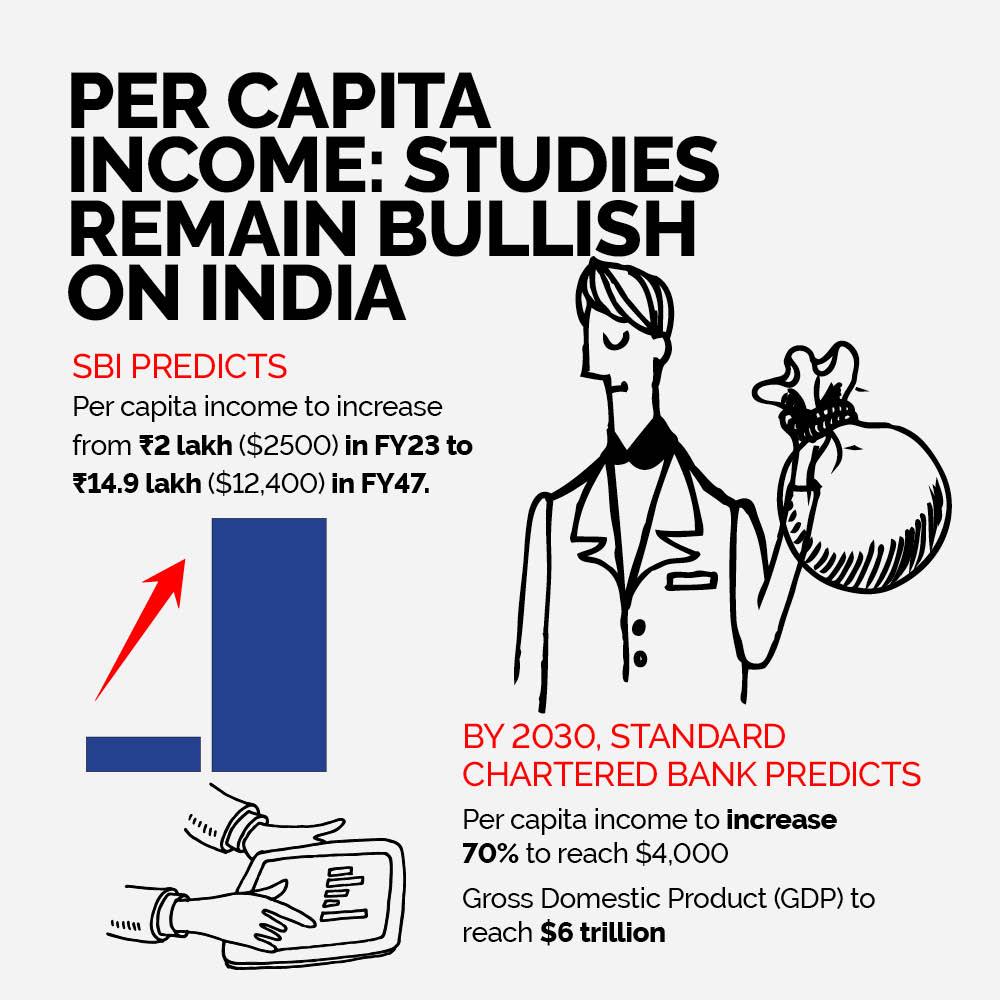

The SBI has also predicted that India’s per capita income is expected to increase from Rs 2 lakh ($2500) in FY23 to Rs 14.9 lakh ($12,400) in FY47.

The Standard Chartered Bank (SCB), meanwhile, estimates that by 2030, the per capita income of India is likely to grow around 70 per cent to reach $4,000 from current levels of $2,450. SCB also predicts that this rise in per capita income will help India become a middle-income economy with a GDP of $6 trillion by 2030.

One argument that is being made to suggest that India cannot overcome a supposed lower-middle income trap by 2047 is that the country’s population would have aged substantially by then. While an ageing population remains a big concern – one which the government must take concrete steps to address – to suggest that India will grow old before it gets rich would certainly be premature.

For example, the SBI also estimates that the Indian population will increase to 1610 million in FY47 from 1400 million in FY23. As a result, the workforce with a taxable base is expected to increase to 565 million in FY47 from 313 million in FY23, increasing its share from 59.1 per cent in FY23 to 78 per cent in FY47. Meanwhile, the number of taxpayers is expected to increase from 70 million in FY23 to 482 million in FY47.

Economic momentum is shifting away from China to India, as is evident from the interest global manufacturers are showing in investing in India. That such a shift will have a transformative impact on the Indian economy is well known. However, the fact that Indians’ per capita incomes stand to gain from this shift deserves more attention. According to an analysis published by the Brookings Institution, India’s per capita income is expected to grow at an average 3.5 per cent faster rate than that in China, on account of strong investments in labour, human capital and structural reforms since 2014.

Brookings Institution attributed the growth momentum to strong structural reforms undertaken by India since 2014. The analysis also reveals that between 2010 and 2019, per-capita GDP growth in India was higher than that in China for the first decade after the 1960s. Between 2010 and 2019, India’s purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita income grew at 5.2 per cent versus 4.5 per cent in China.

More Indians are Entering the Middle Class, an Indicator of Rising Incomes

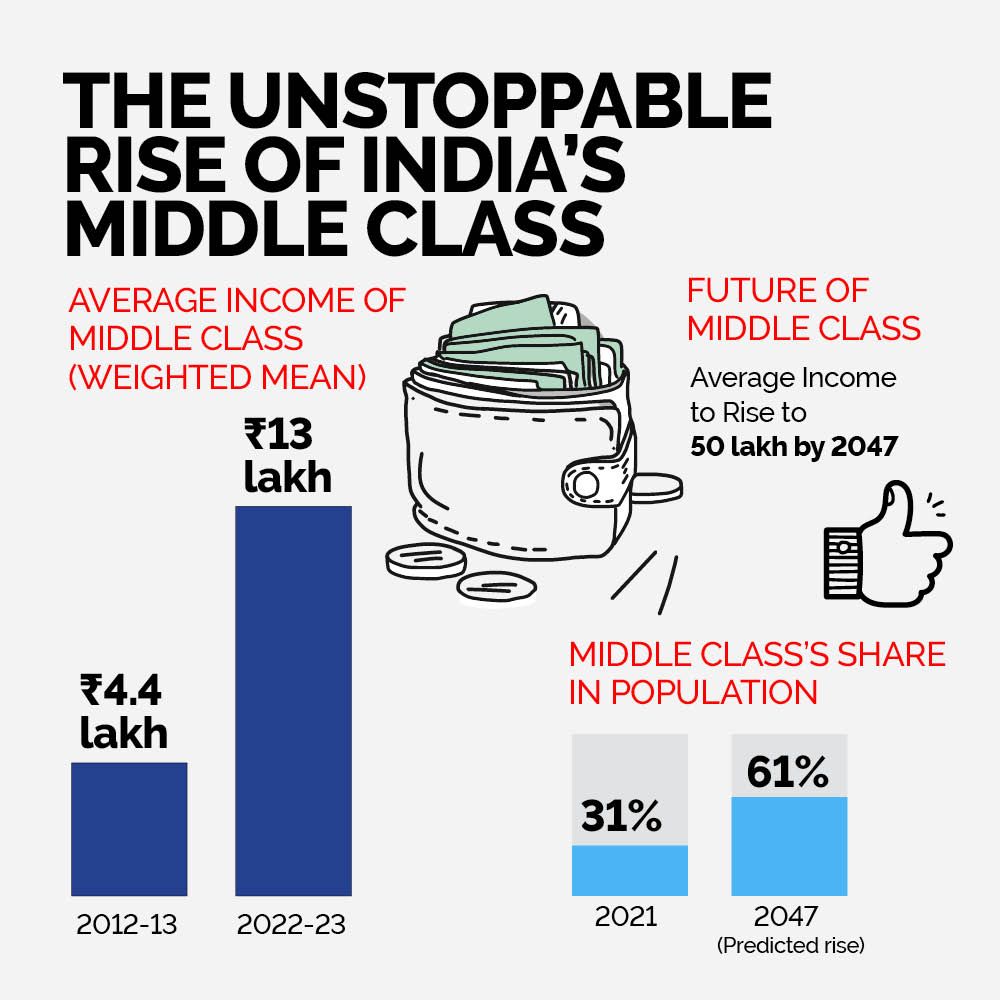

If more people are entering the middle class, that means they are moving up the economic ladder. That, in itself, is a sign of rising incomes. The average income of the middle class (weighted mean) has grown from Rs 4.4 lakh in FY2012-13 to Rs 13 lakh in FY22. Compared to 2011, 13.6 per cent of the population has left the lower income strata and migrated upwards by 2022. While there is a huge chunk of Indians who currently earn less than Rs 5 lakh every year, this group is soon expected to rise up the ladder, enter the middle class and start contributing to the nation’s tax pool.

The average income of people in the middle class is expected to go up to Rs 50 lakh by 2047, according to SBI. In 2020-21, the Indian middle class constituted just about 31 per cent of the total population. However, the size of India’s middle class will nearly double to 61 per cent of its total population by 2047!

Meanwhile, a report by Deloitte India sees middle-income households in rural India experiencing remarkable growth rates, far surpassing their urban counterparts. Going forward, tier-II and tier-III cities are expected to contribute approximately 66 per cent to the country’s growth, while tier-I cities will account for the remaining 33 per cent.

This shows that the fruits of economic development are not restricted to urban, metropolitan India. In fact, suburban and rural India is expected to emerge as the dominant driver of economic growth. Naturally, that means incomes in such regions will rise. The cumulative impact this will have on India’s per capita income simply cannot be ignored.

Finally, one must remember that the major motivation of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government to set the goal of a “Viksit Bharat” by 2047 is to significantly improve the financial health of Indians. For a country that never dreamt of truly becoming a developed nation, it is understandable why some fail to grasp the scale of transformation happening in India, today.

There are also assumptions being made that India’s GDP will only grow at 6 per cent every year. Mediocrity breeds contempt, which is why attempts are being made to discount the potential of India to escape the lower-middle income trap by 2047. A new, re-energised and ambitious India, however, is all set to beat pessimism and achieve what some think is unachievable for the country.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment