views

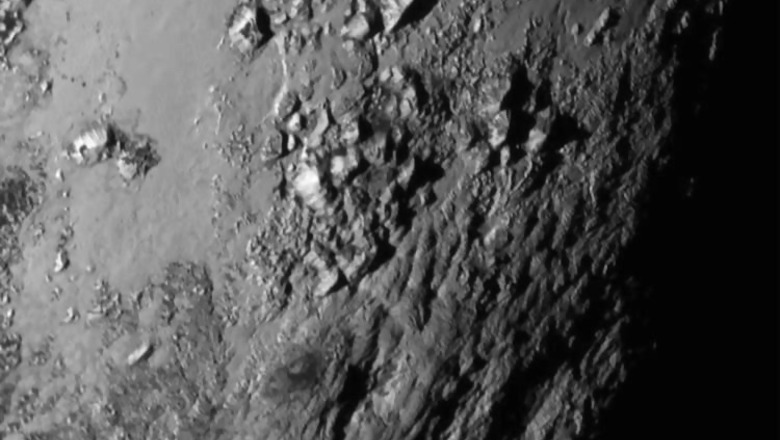

Cape Canaveral, Florida: Mankind's first close-up look at Pluto did not disappoint: The pictures showed ice mountains on Pluto about as high as the Rockies and chasms on its big moon Charon that appear six times deeper than the Grand Canyon.

Especially astonishing to scientists was the total absence of impact craters in a zoom-in shot of one otherwise rugged slice of Pluto. That suggests that Pluto is not the dead ice ball many people think, but is instead geologically active even now, its surface sculpted not by collisions with cosmic debris but by its internal heat, the scientific team reported.

Breathtaking in their clarity, the long-awaited images were unveiled in Laurel, Maryland, home to mission operations for NASA's New Horizons, the unmanned spacecraft that paid a history-making flyby visit to the dwarf planet on Tuesday after a journey of 9 1/2 years and 3 billion miles.

"I don't think any one of us could have imagined that it was this good of a toy store," principal scientist Alan Stern said at a news conference. He marveled: "I think the whole system is amazing. ... The Pluto system is something wonderful."

As a tribute to Pluto's discoverer, Stern and his team named the bright heart-shaped area on the surface of Pluto the Tombaugh Reggio. American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh spied the frozen, faraway world on the edge of the solar system in 1930.

Thanks to New Horizons, scientists now know Pluto is a bit bigger than thought, with a diameter of 1,473 miles, but still just two-thirds the size of Earth's moon. And it is most certainly not frozen in time.

The zoom-in of Pluto, showing an approximately 150-mile swath of the dwarf planet, reveals a mountain range about 11,000 feet high and tens of miles wide. Scientists said the peaks - seemingly pushed up from Pluto's subterranean bed of ice - appeared to be a mere 100 million years old. Pluto itself is 4.5 billion years old.

"Who would have supposed that there were ice mountains?" project scientist Hal Weaver said. "It's just blowing my mind."

John Spencer, like Stern a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, called it "just astonishing" that the first close-up picture of Pluto didn't have a single impact crater. Stern said the findings suggesting a geologically active interior are going to "send a lot of geophysicists back to the drawing boards."

"It could be a game-changer" in how scientists look at other frozen worlds in the Kuiper Belt on the fringes of our solar system, Spencer said. Charon, too, has a surprisingly youthful look and could be undergoing geologic activity.

"We've tended to think of these midsize worlds ... as probably candy-coated lumps of ice," Spencer said. "This means they could be equally diverse and be equally amazing if we ever get a spacecraft out there to see them close up."

The heat that appears to be shaping Pluto may be coming from the decay of radioactive material normally found in planetary bodies, the scientists said. Or it could be coming from energy released by the gradual freezing of an underground ocean.

As for Charon, which is about half the size of Pluto, its canyons look to be 3 miles to 6 miles deep and are part of a cluster of troughs and cliffs stretching 600 miles, or about twice the length of the Grand Canyon, scientists said.

The Charon photo was taken Monday. The Pluto picture was shot just 1 1/2 hours before the spacecraft's moment of closest approach. New Horizons swept to within 7,700 miles of Pluto during its flyby. It is now 1 million miles beyond it.

Up until this week, the best pictures of Pluto were taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, and they were blurry, pixelated images.

Scientists promised even better pictures for the next news briefing on Friday. Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory is in charge of the $720 million mission.

Comments

0 comment