views

Picking a Topic

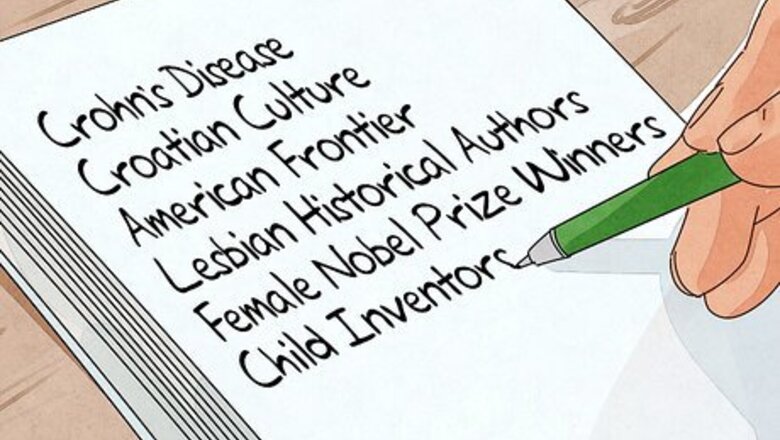

Brainstorm general topics that genuinely interest you. Whether you’re responding to a given assignment prompt or choosing your own direction for original research within a field, your experience will be more meaningful if you pick a subject that you care about. Write down all the possibilities that occur to you so that you have a generous list of options to start from. One way to ensure you have a topic that’s of interest to you to pick a subject to which you have a personal connection. For instance, if your sister has Crohn's Disease, you may be interested in investigating it. Or, if you went on an exchange program to Croatia, you might be keen to know more about its history or culture. Another way to trim down your possibilities is to see if there any patterns that emerge from the longer list. For example, if you wrote down “Gertrude Stein” and “Djuna Barnes,” you could focus on lesbian expat authors.

Do preliminary research to pick a topic. Select your top choices from the list you created to pursue further. Take time to do some background reading on each in general reference texts like encyclopedias and to do keyword searches in a library database to see what textual and online sources are available in relation to each potential topic. Then, select one to focus on that you find the most interesting and that has sufficient resources to investigate. You want to choose a topic that has some, but not too much information available on it. If there are some substantive related resources out there, you know you’re on the right track; if there are pages and pages of relevant search results, you can tell that plenty of people have already gone down that road or that the topic is likely too big to cover and you will need to narrow it further.

Start broad and narrow your focus. Once you have a general topic that interests you, begin by reading widely about it. Write down the ideas, information, and sources that interest you the most. Then, review your notes to start refining your topic into a precise, narrow research focus. For instance, if you are interested in the mapping of the human genome, read about the general history of the scientific advances that have allowed us to map DNA and see if there’s a particular subtopic that catches your eye. Instead of trying to cover the entire subject, limit your scope to focus on the discovery of a gene related to a specific trait or disease or on a particular application, like the regulation of gene therapy for unborn fetuses. EXPERT TIP Kim Gillingham, MA Kim Gillingham, MA Master's Degree, Library Science, Kutztown University Kim Gillingham is a retired library and information specialist with over 30 years of experience. She has a Master's in Library Science from Kutztown University in Pennsylvania, and she managed the audiovisual department of the district library center in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, for 12 years. She continues to do volunteer work for various libraries and lending library projects in her local community. Kim Gillingham, MA Kim Gillingham, MA Master's Degree, Library Science, Kutztown University Use your interests to narrow your focus. Retired librarian, Kim Gillingham, adds: "You can start with a general topic such as Outer Space. Then ask yourself specific questions such as 'What am I interested in about Outer Space?' It could be the history of space exploration, the technology of space exploration, or 'Is Pluto a planet or not?' As always, librarians can be of immense help in narrowing down a topic through a technique called the Reference Interview — try asking your librarian about it!"

Consult with a relevant scholar. It’s good to vet your ideas with an established academic or other professional related to the field in which you’ll be conducting your research. If you’re having trouble deciding among topics or narrowing your scope, seek advice and suggestions from your professor, advisor, or another knowledgeable professional. When you meet with or email them, explain the research that you’ve already conducted to show them that you’ve done your homework. Then, ask something like, “I’m most interested in looking into coming of age rituals in contemporary indigenous cultures, and I was wondering if you think that’s a good topic to pursue and if you had any suggestions for specific case studies or other resources related to it.” Remember: they may be able to point you in a more specific direction based on your general interests, but don’t expect them to do the whole selection process for you. If you’re doing independent research to earn a degree (rather than to fulfill the requirements of a particular class), you should also ask them about the potential marketability of your subject since your topic will be setting the direction for your future career.

Developing Your Research Question

Formulate a research question. Your research should be seeking to answer a particular question; ideally, one that has not been asked before or one that has not yet been satisfactorily answered. Once you have a specific topic, the next step is to refine it into a focused research question. After you conduct your preliminary research, think about the gaps that you noticed in the information available on the subject that you’ve been investigating. Devise a question that could address that missing information. One concrete way to do this is to explore the relationship between two ideas, concepts, phenomena, or events that came up in your research but whose relationship has not been fully investigated. For example, “how did political radicals influence popular representations of sexuality in the 1920s United States?” Another concrete way to formulate your question is to consider how an existing methodology or concept applies to a new, specific context or case study. For instance, you could think of how Sigmund Freud’s idea of the “appendage” applies to a specific virtual reality game.

Make sure that your question is answerable. Now that you have a focused research inquiry, it’s time to test its feasibility. If you cannot address your question with existing research or conduct the research necessary to address it, then you need to pick another topic. For example, if your question requires conducting a study that’s not feasible given your timeframe or the resources available to you, then you need to find a way to revise your question so that you can answer it. Sometimes if your topic is too new, there won’t be a substantial enough body of research available for you to do a comprehensive analysis of it. In that case, you may need to revise or broaden your question so that you can actually answer it.

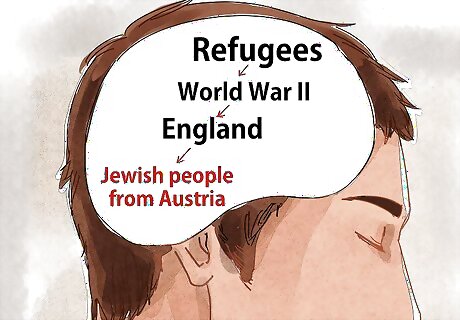

Make sure that your question is manageable. It should be narrow enough that you can answer it within the space that you have but not so narrow that you can’t fulfill the page or research requirements. If your question is not narrow enough, refine your focus further by limiting your topic according to a given historical era, theoretical approach, geographical region, demographic or culture, industry or field. For example, if you’re interested in refugees, you might limit your scope by honing in on a particular event (World War II) and/or time period (the 1940s), a specific location (England) and/or population (Jewish people from Austria).

Make sure that your question is worth answering. You want to settle on a question that matters, one that has real stakes in that it has some direct, real-life application and/or makes an original contribution to your field. If you find yourself asking “so what?” about the possible answers to your question, then it’s time to revise your topic.

Making Sure that You’re on the Right Track

Review the guidelines. Now that you’ve settled on a question, it’s time to check that your research topic meets with all the requirements that you’re trying to address, whether they’re for a class assignment, thesis, or grant. Be sure that your question fits with the guidelines for your research project’s topic, methods, and scope. You might have a brilliant research question, but, if it’s about genetic disorders and the grant you’re applying for only funds research on communicable diseases, you’ll need to go back to the drawing board. Also be sure to take the required length of the project into consideration. For instance, if your question is too narrow or specific, you might not be able to hit the 250-page requirement for a doctoral thesis.

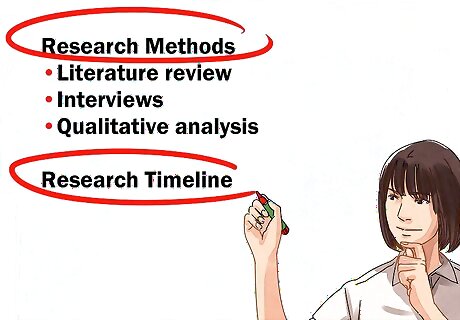

Create a research plan. Now that you have an idea of what you’ll be addressing, you need to figure out how you’ll be addressing it. Take time to detail a strategy for how and when you’ll do the necessary research. Start by listing the various research methods that you’ll use, such as a literature review, interviews, and qualitative analysis. Then, create a timeline for when you’ll be doing each kind of research, being sure to leave enough time for yourself to complete the writing. Think about your writing style, too. A humanities-related paper may have more of a storytelling writing style, while a more technical or scientific paper will be much more matter-of-fact.

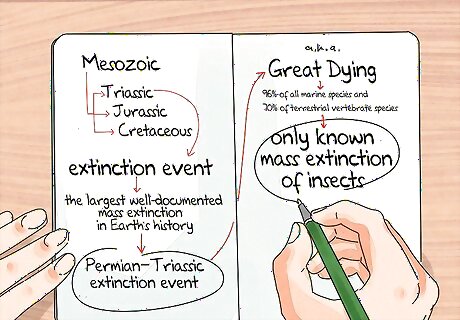

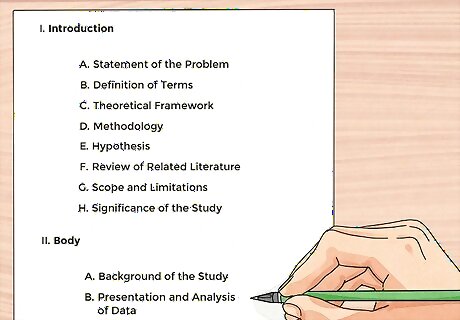

Build a research outline. Especially with complex research, it’s useful to construct a tentative outline that can help focus your efforts. Start by listing the topics and concepts that you will need to cover in order to answer your research question in a thorough way. Once you have your list, group together related topics and organize those groups into a logical order. You can order topics chronologically (for instance, if you’re studying a historical event). Most often, you’ll order them according to the progression of your argument, with one idea building on the last. Remember that in order to answer your question, you will need to contextualize it. The first part of your outline should address the necessary background information, studies, and/or debates that informed your question. For instance, if you’re analyzing the role of female elected officials from Sweden in the 1970s, you’d want to cover a history of women in the country’s government, investigate public understandings of gender at that cultural moment, and review any existing studies of the topic. Keep in mind that some research topics will need more context than others. For instance, a humanities- or history-related topic will need a lot of backstory and context. Your research may change the structure or content of your outline, but it’s still useful to have a well-developed starting point.

Consult with your advisor. Now that you have a solid question, plan, and outline, take it to the person overseeing your research to make sure that they approve of your research topic and approach. Since they are the person who will be guiding and evaluating your research, it’s always best to get their approval, feedback, and suggestions before embarking on any project.

Comments

0 comment