views

A

x

=

b

{\displaystyle A\mathbf {x} =\mathbf {b} }

involves a matrix acting on a vector to produce another vector. In general, the way

A

{\displaystyle A}

acts on

x

{\displaystyle \mathbf {x} }

is complicated, but there are certain cases where the action maps to the same vector, multiplied by a scalar factor.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors have immense applications in the physical sciences, especially quantum mechanics, among other fields.

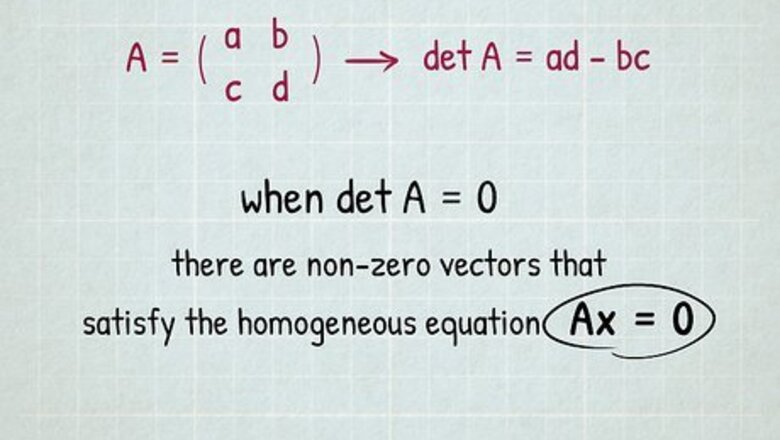

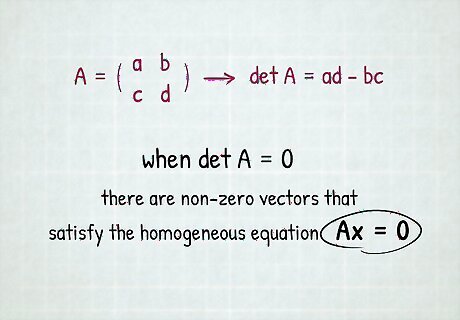

Understand determinants. The determinant of a matrix det A = 0 {\displaystyle \det A=0} \det A=0 when A {\displaystyle A} A is non-invertible. When this occurs, the null space of A {\displaystyle A} A becomes non-trivial - in other words, there are non-zero vectors that satisfy the homogeneous equation A x = 0. {\displaystyle A\mathbf {x} =0.} A{\mathbf {x}}=0.

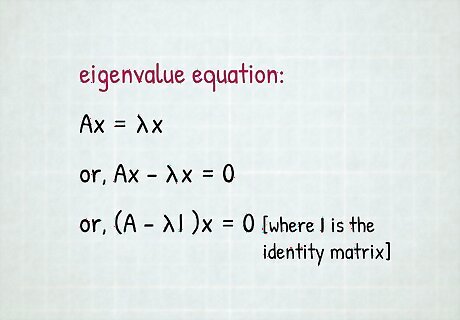

Write out the eigenvalue equation. As mentioned in the introduction, the action of A {\displaystyle A} A on x {\displaystyle \mathbf {x} } {\mathbf {x}} is simple, and the result only differs by a multiplicative constant λ , {\displaystyle \lambda ,} \lambda , called the eigenvalue. Vectors that are associated with that eigenvalue are called eigenvectors. A x = λ x {\displaystyle A\mathbf {x} =\lambda \mathbf {x} } A{\mathbf {x}}=\lambda {\mathbf {x}} We can set the equation to zero, and obtain the homogeneous equation. Below, I {\displaystyle I} I is the identity matrix. ( A − λ I ) x = 0 {\displaystyle (A-\lambda I)\mathbf {x} =0} (A-\lambda I){\mathbf {x}}=0

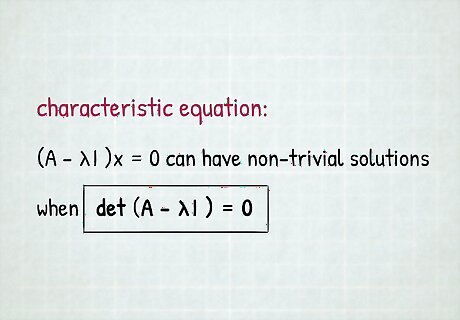

Set up the characteristic equation. In order for ( A − λ I ) x = 0 {\displaystyle (A-\lambda I)\mathbf {x} =0} (A-\lambda I){\mathbf {x}}=0 to have non-trivial solutions, the null space of A − λ I {\displaystyle A-\lambda I} A-\lambda I must be non-trivial as well. The only way this can happen is if det ( A − λ I ) = 0. {\displaystyle \det(A-\lambda I)=0.} \det(A-\lambda I)=0. This is the characteristic equation.

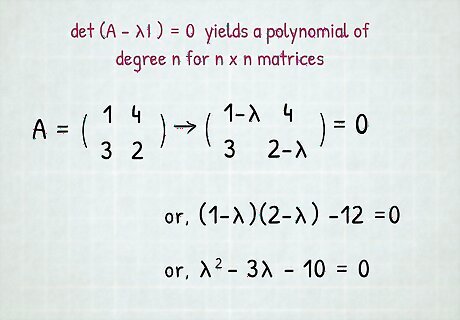

Obtain the characteristic polynomial. det ( A − λ I ) {\displaystyle \det(A-\lambda I)} \det(A-\lambda I) yields a polynomial of degree n {\displaystyle n} n for n × n {\displaystyle n\times n} n\times n matrices. Consider the matrix A = ( 1 4 3 2 ) . {\displaystyle A={\begin{pmatrix}1&4\\3&2\end{pmatrix}}.} A={\begin{pmatrix}1&4\\3&2\end{pmatrix}}. | 1 − λ 4 3 2 − λ | = 0 ( 1 − λ ) ( 2 − λ ) − 12 = 0 {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\begin{vmatrix}1-\lambda &4\\3&2-\lambda \end{vmatrix}}&=0\\(1-\lambda )(2-\lambda )-12&=0\end{aligned}}} {\begin{aligned}{\begin{vmatrix}1-\lambda &4\\3&2-\lambda \end{vmatrix}}&=0\\(1-\lambda )(2-\lambda )-12&=0\end{aligned}} Notice that the polynomial seems backwards - the quantities in parentheses should be variable minus number, rather than the other way around. This is easy to deal with by moving the 12 to the right and multiplying by ( − 1 ) 2 {\displaystyle (-1)^{2}} (-1)^{{2}} to both sides to reverse the order. ( λ − 1 ) ( λ − 2 ) = 12 λ 2 − 3 λ − 10 = 0 {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}(\lambda -1)(\lambda -2)&=12\\\lambda ^{2}-3\lambda -10&=0\end{aligned}}} {\begin{aligned}(\lambda -1)(\lambda -2)&=12\\\lambda ^{{2}}-3\lambda -10&=0\end{aligned}}

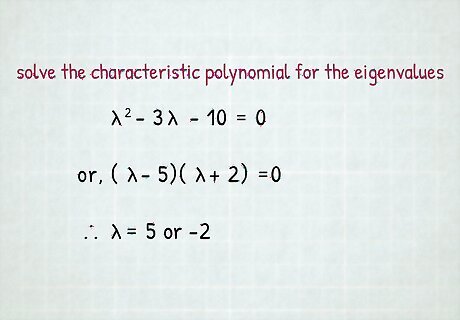

Solve the characteristic polynomial for the eigenvalues. This is, in general, a difficult step for finding eigenvalues, as there exists no general solution for quintic functions or higher polynomials. However, we are dealing with a matrix of dimension 2, so the quadratic is easily solved. ( λ − 5 ) ( λ + 2 ) = 0 λ = 5 , − 2 {\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&(\lambda -5)(\lambda +2)=0\\&\lambda =5,-2\end{aligned}}} {\begin{aligned}&(\lambda -5)(\lambda +2)=0\\&\lambda =5,-2\end{aligned}}

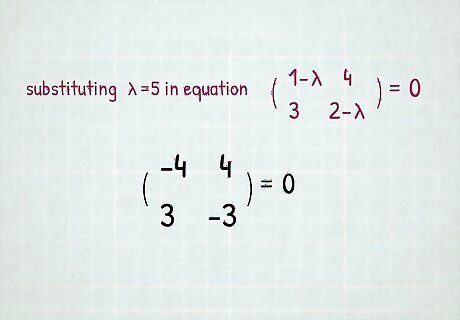

Substitute the eigenvalues into the eigenvalue equation, one by one. Let's substitute λ 1 = 5 {\displaystyle \lambda _{1}=5} \lambda _{{1}}=5 first. ( A − 5 I ) x = ( − 4 4 3 − 3 ) {\displaystyle (A-5I)\mathbf {x} ={\begin{pmatrix}-4&4\\3&-3\end{pmatrix}}} (A-5I){\mathbf {x}}={\begin{pmatrix}-4&4\\3&-3\end{pmatrix}} The resulting matrix is obviously linearly dependent. We are on the right track here.

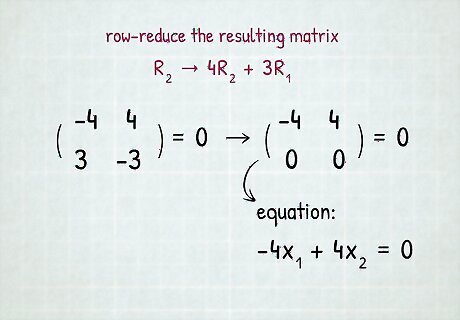

Row-reduce the resulting matrix. With larger matrices, it may not be so obvious that the matrix is linearly dependent, and so we must row-reduce. Here, however, we can immediately perform the row operation R 2 → 4 R 2 + 3 R 1 {\displaystyle R_{2}\to 4R_{2}+3R_{1}} R_{{2}}\to 4R_{{2}}+3R_{{1}} to obtain a row of 0's. ( − 4 4 0 0 ) {\displaystyle {\begin{pmatrix}-4&4\\0&0\end{pmatrix}}} {\begin{pmatrix}-4&4\\0&0\end{pmatrix}} The matrix above says that − 4 x 1 + 4 x 2 = 0. {\displaystyle -4x_{1}+4x_{2}=0.} -4x_{{1}}+4x_{{2}}=0. Simplify and reparameterize x 2 = t , {\displaystyle x_{2}=t,} x_{{2}}=t, as it is a free variable.

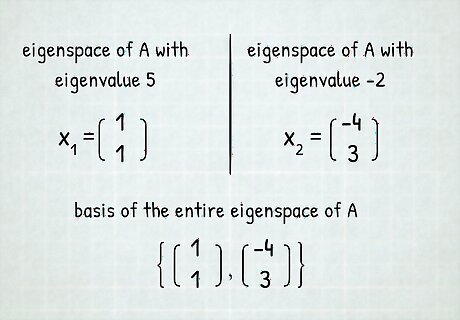

Obtain the basis for the eigenspace. The previous step has led us to the basis of the null space of A − 5 I {\displaystyle A-5I} A-5I - in other words, the eigenspace of A {\displaystyle A} A with eigenvalue 5. x 1 = ( 1 1 ) {\displaystyle \mathbf {x_{1}} ={\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\end{pmatrix}}} {\mathbf {x_{{1}}}}={\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\end{pmatrix}} Performing steps 6 to 8 with λ 2 = − 2 {\displaystyle \lambda _{2}=-2} \lambda _{{2}}=-2 results in the following eigenvector associated with eigenvalue -2. x 2 = ( − 4 3 ) {\displaystyle \mathbf {x_{2}} ={\begin{pmatrix}-4\\3\end{pmatrix}}} {\mathbf {x_{{2}}}}={\begin{pmatrix}-4\\3\end{pmatrix}} These are the eigenvectors associated with their respective eigenvalues. For the basis of the entire eigenspace of A , {\displaystyle A,} A, we write { ( 1 1 ) , ( − 4 3 ) } . {\displaystyle \left\{{\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}-4\\3\end{pmatrix}}\right\}.} \left\{{\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}-4\\3\end{pmatrix}}\right\}.

Comments

0 comment