views

Exploring Your Feelings

Recognize that high sensitivity is innate to you. Neuroscientists have discovered that part of our capacity for emotional sensitivity is linked to our genes. About 20% of the world’s population may be “highly sensitive,” meaning they have a greater awareness of subtle stimuli that is lost on most people and have more intense experiences of those stimuli. This increased sensitivity is linked to a gene that influences a hormone called norepinephrine, a “stress” hormone that also works as a neurotransmitter in your brain to trigger attention and responses. Some emotional over-sensitivity is also linked to oxytocin, the hormone responsible for humans’ feelings of love and bonding with each other. Oxytocin can also trigger emotional sensitivity. If you have naturally higher levels of oxytocin, your “innate social reasoning skills” may be heightened, making you more sensitive to perceiving (and possibly misinterpreting) even small cues. Different societies respond to highly sensitive people differently. In many Western cultures, highly sensitive people are often commonly misunderstood as weak or lacking in internal fortitude, and quite often bullied. But this is not true throughout the world. In many places, highly sensitive people are considered gifted, as such sensitivity allows a great ability to perceive and therefore understand others. What is just a character trait can be regarded quite differently depending on the culture you are in, and things such as gender, family environment, and the type of school you go to. While it is possible (and important!) to learn to regulate your emotions more effectively, if you are a naturally sensitive person, you must learn to accept that about yourself. You can become less reactive with practice, but you will never be a completely different person--and you should not try to. Just become the best version of you.

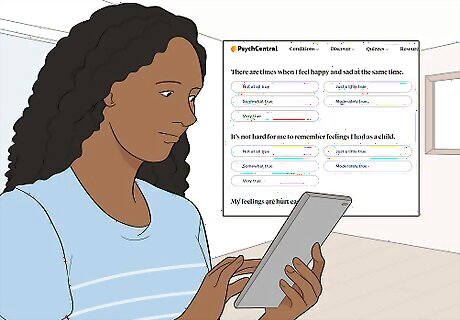

Take a self-assessment. If you are not sure whether you’re overly sensitive, you can take a few steps to assess yourself. One way is to take a questionnaire, such as the one from The Emotionally Sensitive Person available at PsychCentral. These questions can help you reflect on your emotions and experiences. Try not to judge yourself when answering these questions. Answer them honestly. Once you have learned the extent of your sensitivity, you can focus on managing your emotions in a more helpful way. Remember, this is not a matter of being who you think you ought to be. Answer truthfully, whether you are a sensitive person, or a person who thinks they are more sensitive than he or she really is.

Explore your emotions through journaling. Keeping an “emotions journal” can help you track and explore your emotions and your responses. It will help you recognize what may trigger an over-emotional response. It will also help you learn when your responses are appropriate. Try writing down whatever you’re feeling right now and work backwards to think about what may have brought it on. For example, are you feeling anxious? What happened throughout the day that may have triggered this? You may realize that even small events can trigger big emotional responses in you. You can also ask yourself some questions about each entry, such as: How do I feel at this moment? What do I think happened to provoke this response? What do I need when I feel this way? Have I felt like this any time before? You can also try a timed entry. Write a sentence, such as “I feel sad” or “I feel angry.” Set a timer for two minutes and write about everything in your life that is connected to that feeling. Don’t stop to edit or judge your feelings. Just name them for now. Once you’ve done this, look at what you’ve written. Can you detect patterns? Emotions behind the responses? For example, anxiety is often caused by fear, sadness by loss, anger by feeling attacked, etc. You could also try exploring a particular event. For example, perhaps someone on the bus gave you a look that you interpreted as criticizing your appearance. That could hurt your feelings, and you might even feel sad or angry because of it. Try to remind yourself of two things: 1) that you don’t actually know what’s going on in others’ heads, and 2) that others’ judgments of you don’t matter. That “dirty look” could be in reaction to something else entirely. And even if it was a judgment, well, that person doesn’t know you and doesn’t know the many things that make you awesome. Remember to exercise self-compassion in your entries. Don’t judge yourself for your feelings. Remember, you may not be able to control how you feel initially, but you can control how you respond to those feelings.

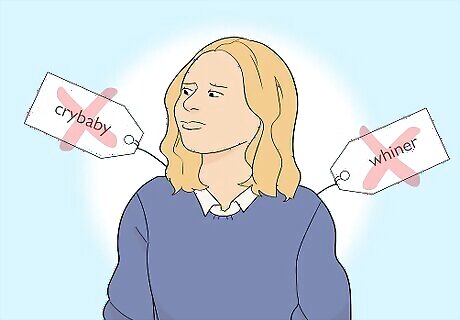

Avoid labeling yourself. Unfortunately, very sensitive people are often insulted and called names, such as “cry-baby” and “whiner”. Even worse, these insults sometimes become descriptive "labels" used by other people. In time, it is easy to adhere this label to yourself, and see yourself not as a sensitive person that does, yes, occasionally cry but 99.5% of the time does not. If you do this, you may focus entirely on one aspect of yourself (that can be problematic) to the extent you define yourself entirely by this. Challenge negative "labels" by re-framing. This means taking the "label", removing it, and look at the situation in a broader context. For example: A teenager cries because of a disappointment and an acquaintance nearby mutters "crybaby" and wanders off. Instead of taking the insult to heart, she thinks: "I know I am not a cry-baby. Yes, I sometimes respond emotionally to situations. Sometimes that means I cry when less sensitive people would not cry. I am working on responding in a more socially appropriate way. Anyway, insulting a person who is already crying is a jerky thing to do. I am caring enough not to do that to someone.”

Identify triggers for your sensitivity. You may know perfectly well what triggered your over-sensitive response, or you may not. Your brain may have developed a pattern of “automatic reactivity” to certain stimuli, such as stressful experiences. Over time, this pattern becomes a habit, until you immediately react in a certain way to an event without even thinking about it. Fortunately, you can learn to retrain your brain and shape new patterns. The next time you experience an emotion, such as panic, anxiety, or anger, stop what you’re doing and shift your focus to your sensory experiences. What are your five senses doing? Don’t judge your experiences, but note them. This is a practice of “self-observation,” and it can help you tease apart the multiple “information streams” that make up experiences. Often, we feel overwhelmed or swamped by an emotion and can’t distinguish the jumble of emotions and sensory experiences that are all firing at once. Slowing down, focusing on your individual senses, and separating these information paths will help you restructure your brain’s “automatic” habits. For example, your brain might react to stress by sending your heart rate skyrocketing, which could make you feel jittery and nervous. Knowing that this is your body’s default response will help you interpret your reactions differently. Journaling can also help you with this. Each time you feel like you’re responding emotionally, write down the moment you felt you became emotional, what you were feeling, what your body’s senses experienced, what you were thinking, and the details of the circumstances. Armed with this knowledge, you can help train yourself to respond differently. Sometimes, sensory experiences such as being in a particular place or even smelling a familiar fragrance can set off an emotional reaction. This is not always “over-sensitivity.” For example, smelling apple pie might trigger an emotional reaction of sadness, because you and your late grandmother used to make apple pies together. Acknowledging this response is healthy. Consciously dwell on it a moment, and realize why it’s having that effect: “I am experiencing sadness because I had a lot of fun making pies with my grandmother. I miss her.” Then, once you have honored the feeling, you can move to something positive: “I’ll make an apple pie today to remember her.”

Examine whether you could be codependent. Codependent relationships happen when you feel like your self-worth and identity are dependent on someone else’s actions and responses. You may feel like your purpose in life is to make sacrifices for your partner. You may feel devastated if your partner disapproves of something you do or feel. Codependency is very common in romantic relationships, but it can happen in any type of relationship. The following are signs of codependent relationships: You feel like your satisfaction about your life is tied to a specific person You recognize unhealthy behaviors in your partner but stay with them despite them You go to great lengths to support your partner, even when it means sacrificing your own needs and health You constantly feel anxiety about your relationship status You don’t have a good sense of personal boundaries You feel terrible about saying “no” to anyone or anything You react to everyone’s thoughts and feelings by either agreeing with them or becoming immediately defensive Codependency can be treated. Professional mental health counseling is the best idea, although there are also support group programs such as Co-Dependents Anonymous that may help.

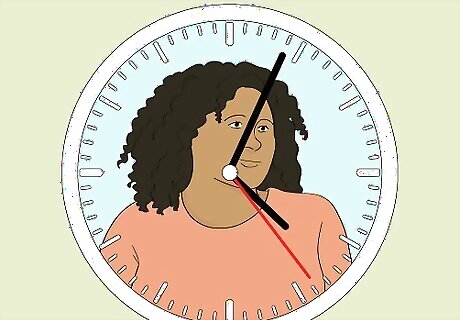

Take it slowly. Exploring your emotions, especially the sensitive areas, is hard work. Don’t push yourself too hard all at once. Psychology has shown that stepping outside your comfort zone is necessary for growth, but trying to do too much too fast can actually lead to setbacks. Try setting an “appointment” with yourself to examine your sensitivities. Say you’ll explore it for 30 minutes a day. Then, after you’ve done the emotional work for the day, allow yourself to do something relaxing or enjoyable to refresh yourself. Take note of when you might be avoiding thinking about your sensitivities because it feels uncomfortable or too hard. Procrastination is often driven by fear: we fear that an experience will be unpleasant, and so we put off doing it. Remind yourself that you’re strong enough to do this, and then tackle it. If you’re having a really tough time working up the gumption to face your emotions, try setting a very achievable goal for yourself. Start with 30 seconds, if you want to. All you have to do is face your sensitivities for 30 seconds. You can do that. When you’ve accomplished that, set yourself another 30 seconds. You’ll find that your mini-accomplishments will help you build up steam.

Allow yourself to feel your emotions. Moving away from emotional over-sensitivity doesn’t mean that you should stop feeling your emotions altogether. In fact, trying to repress or deny your emotions can cause harm. Instead, your goal should be to acknowledge “unpleasant” emotions like anger, hurt, fear, and grief -- emotions that are just as necessary for emotional health as “positive” ones like joy and delight -- without letting them take over. It's important to be able to label these emotions so that you can figure out how to move forward with them. Try giving yourself a “safe space” to express whatever you’re feeling. For example, if you’re dealing with grief over a loss, give yourself some time each day to let all your feelings out. Set a timer and then journal about your emotions, cry, talk to yourself about your feelings -- whatever you feel you need to do. Once the timer is up, allow yourself to go back to the rest of your day. You will feel better knowing you’ve honored your feelings. You’ll also keep yourself from spending all day wrapped up in a single feeling, which can be harmful. Knowing you will have your “safe space” time to express whatever you’re feeling will make it easier for you to go on with your daily responsibilities.

Examining Your Thoughts

Learn to recognize cognitive distortions that may be making you over-sensitive. Cognitive distortions are unhelpful habits of thinking and responding that your brain has learned over time. You can learn to identify and challenge these distortions when they show up. Cognitive distortions usually don’t occur in isolation. As you explore your thought patterns, you may notice that you experience several of them in response to a single feeling or event. Taking the time to fully examine your responses will help you learn what’s helpful and what isn’t. There are many types of cognitive distortion, but some common culprits for emotional over-sensitivity are personalization, labeling, “should” statements, emotional reasoning, and jumping to conclusions.

Recognize and challenge personalization. Personalization is a very common distortion that can cause emotional over-sensitivity. When you personalize, you make yourself the cause for things that may have nothing to do with you, or that you can’t control. You may also take things “personally” when they are not aimed at you. For example, if your child receives some negative comments from her teacher about her behavior, you might personalize this critique as directed at you as a person: “Dana’s teacher thinks I’m a bad father! How dare she insult my parenting?” This interpretation could lead you to an over-sensitive reaction because you’re interpreting a critique as blame. Instead, try to look at the situation logically (this will take practice, so be patient with yourself). Explore exactly what’s happening and what you know about the situation. If Dana’s teacher sent home comments that she needs to pay more attention in class, for example, this isn’t blaming you for being a “bad” parent. It’s giving you information you can use to help your child do better in school. It’s an opportunity for growth, not shame.

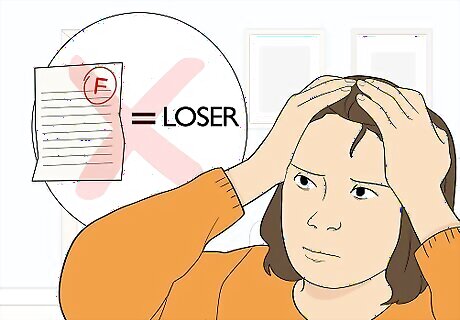

Recognize and challenge labeling. Labeling is a type of “all-or-nothing” thinking. It often occurs in conjunction with personalization. When you label yourself, you generalize yourself based on a single action or event, instead of recognizing that what you do isn’t the same as who you are. For example, if you get negative comments back on an essay, you might label yourself a “failure” or a “loser.” Labeling yourself as a “failure” means you feel like you’ll never get any better so you shouldn’t even bother trying. It can lead to feelings of guilt and shame. It also makes it very hard for you to accept constructive criticism, because you see any critique as a sign of “failure.” Instead, recognize mistakes and challenges for what they are: specific situations from which you can learn to grow for the future. Instead of labeling yourself a “failure” when you get a bad grade on an essay, acknowledge your errors and think about what you can learn from the experience: “Okay, I didn’t do very well on this essay. That’s disappointing, but it’s not the end of the world. I’ll talk with my teacher about what I can improve for next time.”

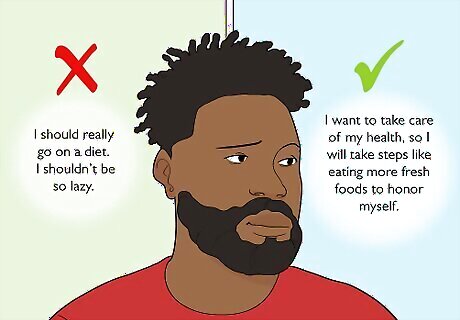

Recognize and challenge “should statements.” Should statements cause harm because they hold you (and others) to standards that are often unreasonable. They often rely on external ideas rather than things that are truly meaningful to you. When you violate a “should,” you may punish yourself for it, decreasing your motivation for change even further. These ideas can cause guilt, frustration, and anger. For example, you might tell yourself, “I should really go on a diet. I shouldn’t be so lazy.” You’re essentially trying to “guilt” yourself into acting, but guilt isn’t a very good motivator. You can challenge “should” statements by examining what is really going on behind the “should.” For example, do you think you “should” go on a diet because others have told you to? Because you feel pressure from social standards to look a certain way? These are not healthy or helpful reasons to do something. However, if you feel like you “should” go on a diet because you’ve talked with your doctor and agreed it would be good for your health, you can transform your “should” into something more constructive: “I want to take care of my health, so I will take steps like eating more fresh foods to honor myself.” This way, you are not being over-critical towards yourself, rather you are using positive motivation -- and that’s way more effective in the long run. Should statements can also cause emotional over-sensitivity when you direct them against others. For example, you may get frustrated if you’re having a conversation with someone who doesn’t react the way you want them to. If you tell yourself, “She should be excited about what I’m telling her,” you will be frustrated and very likely hurt if the person doesn’t feel what you’ve told yourself she “should.” Remember that you cannot control others’ feelings or responses. Try to avoid going into situations with others expecting certain actions or reactions.

Recognize and challenge emotional reasoning. When you use emotional reasoning, you assume that your feelings are facts. This type of distortion is very common, but with a little work, you can learn to identify and fight back against it. For example, you might feel hurt because your boss pointed out some errors in a big project you just completed. If you used emotional reasoning, you might assume that your boss is being unfair because you are having negative feelings. You might assume that because you feel like a “loser,” you are actually a worthless employee. These assumptions don’t have logical evidence. To challenge emotional reasoning, try writing down a few situations where you experience negative emotional reactions. Then, write down the thoughts that went through your mind. Write down the feelings you experienced after you had these thoughts. Finally, examine the actual consequences to the situation. Do they fit with what your emotions told you were the “reality”? You’ll often find that your feelings really weren’t good evidence after all.

Recognize and challenge jumping to conclusions. Jumping to conclusions is pretty similar to emotional reasoning. When you jump to conclusions, you latch on to a negative interpretation of a situation without any facts to support your interpretation. In extreme cases, you may catastrophize, where you allow your thoughts to spiral out of control until you reach the worst possible of all scenarios. “Mind-reading” is a type of jumping to conclusions that can contribute to emotional over-sensitivity. When you mind-read, you assume that people are reacting negatively to something about you, even when you don’t have any evidence for this. For example, if your partner doesn’t text you back in response to your question about what she’d like for dinner, you may assume that she is ignoring you. You have no evidence that this is the case, but this hasty interpretation can cause you to feel hurt or even angry. Fortune-telling is another type of jumping to conclusions. This happens when you predict that things will turn out badly, regardless of any evidence you may have. For example, you might not even propose a new project at work because you assume that your boss will shoot it down. An extreme form of jumping to conclusions happens when you “catastrophize.” For example, if you don’t get a response text from your partner, you might assume she’s angry with you. You might then jump to the idea that she is avoiding talking with you because she has something to hide, like the fact that she actually doesn’t love you any more. You might then jump to the idea that your relationship is falling apart and that you will end up living alone in your mom’s basement. This is an extreme example, but it demonstrates the kind of logical leaps that can happen when you let yourself jump to conclusions. Challenge mind-reading by talking openly and honestly with people. Don’t approach them from a place of accusations or blame, but ask what’s really going on. For example, you could text your partner, “Hey, is there something going on that you’d like to talk about?” If your partner says no, take her at her word. Challenge fortune-telling and catastrophizing by examining the logical evidence for each step of your thought process. Do you have past evidence for your assumption? Do you observe anything in the current situation that is actual evidence for your thoughts? Often, if you take the time to work through your response step-by-step, you’ll catch yourself making a logical leap that just isn’t supported. With practice, you’ll get better at stopping these leaps.

Taking Action

Meditate and practice mindfulness. Meditation, especially mindfulness meditation, can help you manage your responses to emotions. It can even help improve your brain’s reactivity to stressors. Mindfulness focuses on acknowledging and accepting your emotions in the moment without judging them. This is very helpful for overcoming emotional over-sensitivity. You can take a class, use a guided online meditation, or learn to do mindfulness meditation on your own. Find a quiet place where you won’t be interrupted or distracted. Sit upright, either on the floor or in a straight-backed chair. Slouching makes it hard to breathe properly. Begin by focusing on a single element of your breathing, such as the feeling of your chest rising and falling or the sound your breathing makes. Focus on this element for a few minutes as you take deep, even breaths. Expand your focus to include more of your senses. For example, start to focus on what you hear, smell, and touch. It can help you to keep your eyes closed, as we tend to get visually distracted easily. Accept the thoughts and sensations you experience, but don’t judge anything as “good” or “bad.” It can help to consciously acknowledge them as they arise, especially at first: “I am experiencing that my toes are cold. I am having the thought that I’m distracted.” If you feel yourself getting distracted, bring your focus back to your breathing. Spend about 15 minutes in meditation every day. You can find online guided mindfulness meditations from the UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center and BuddhaNet.

Learn assertive communication. Sometimes, people become over-sensitive because they have not communicated their needs or feelings clearly to others. When you are overly passive in your communication, you have trouble saying “no” and you do not communicate your thoughts and feelings clearly and honestly. Learning assertive communication will help you communicate your needs and feelings to others, which may help you feel heard and valued. Use “I”-statements to communicate your feelings, e.g. “I felt hurt when you were late to our date” or “I prefer to leave early for appointments because I feel anxious if I think I might be late.” This avoids sounding like you’re blaming the other person and keeps the focus on your own emotions. Ask follow-up questions when having a conversation. Especially if the conversation is emotionally loaded, asking questions to clarify your understanding will help keep you from overreacting. For example, after the other person has finished speaking, say: “What I heard you say is_____. Is that right?” Then give the other person a chance to clarify. Avoid “categorical imperatives.” These words, like “should” or “ought,” place a moral judgment on others’ behavior and can feel like you’re being blaming or demanding. Try substituting “I prefer” or “I want you to” instead. For example, instead of “You should remember to take out the trash,” say “I want you to remember to take out the trash because I feel like I have to shoulder all the responsibilities when you forget.” Kick assumptions to the curb. Don’t assume that you know what’s going on. Invite others to share their thoughts and experiences. Use phrases such as “What do you think?” or “Do you have any suggestions?” Acknowledge that others have different experiences. Fighting over who is “right” in a situation can leave you feeling overstimulated and angry. Emotions are subjective; remember that there is usually no “right” answer involving them. Use phrases such as “My experience is different,” along with acknowledging the other person’s emotions, to make room for everyone’s experiences.

Wait to act until you’ve cooled down. Your emotions can interfere with how you respond to situations. Acting in the heat of an emotion may lead you to do things you regret later. Give yourself a break, even if it’s just for a few minutes, before responding to a situation that’s prompted a major emotional response. Ask yourself the “If...then” question. “IF I do this right now, THEN what may happen later?” Consider as many consequences -- both positive and negative -- for your action as possible. Then, weigh the consequences against the action. For example, perhaps you just had a very heated argument with your spouse. You are so angry and hurt that you feel like you want to ask for a divorce. Take a time-out and ask yourself the “If...then” question. If you ask for a divorce, what may happen? Your spouse could feel hurt or unloved. S/he may remember it later when both of you have cooled off and see it as a sign s/he cannot trust you when you’re angry. S/he could agree to it in a fight of his/her own anger. Do you want any of these consequences? Reader Poll: We asked 367 wikiHow readers, and 54% of them agreed that the best way to cope with feeling upset or irritated is to take a break from the person or situation that is bothering you. [Take Poll]

Approach yourself and others with compassion. You may find yourself avoiding situations that stress you out or feel unpleasant because of your over-sensitivity. You may assume that any mistake in a relationship is a deal-breaker, so you avoid relationships altogether, or only have shallow ones. Approach others (and yourself) with compassion. Assume the best about people, especially those who know you. If your feelings are hurt, don’t assume that it was intentional: show compassionate understanding that everyone, including friends and loved ones, makes mistakes. If you did experience hurt feelings, use assertive communication to express them to your loved one. S/he may not even be aware that s/he hurt you, and if s/he loves you, s/he’ll want to know how to avoid that hurt in the future. Do not criticize the other person. For example, if your friend forgot that you had a lunch date and you felt hurt, don’t approach it by saying “You forgot me and you hurt my feelings.” Instead, say, “I felt hurt when you forgot our lunch date, because spending time together is important to me.” Then follow it up with an invitation to share your friend’s experiences: “Is something going on? Would you like to talk about it?” Remember that others may not always feel like discussing their emotions or experiences, especially if they’re still new or raw. Don’t take it personally if your loved one doesn’t want to talk immediately. It is not a sign that you’ve done anything wrong; s/he just needs some time to process his/her feelings. Approach yourself the way you would a friend whom you love and care for. If you would not say something hurtful or judgmental to a friend, why would you do it to yourself?

Seek professional help if necessary. Sometimes, you can do your best to manage your emotional sensitivities and still feel overwhelmed by them. Working with a licensed mental health professional can help you explore your feelings and responses in a safe, supportive environment. A trained counselor or therapist can help you discover unhelpful ways of thinking and teach you new skills to manage your feelings in healthy ways. Sensitive people may need additional help learning to manage negative emotions and skills to handle emotional situations. This is not necessarily a sign of mental illness, only helping you gain useful skills in negotiating the world. Ordinary people get help from mental health professionals. You do not have to be "mentally ill" or dealing with a devastating issue to get benefit from counselors, psychologists, therapists, or the like. These are health professionals, just as much as dental hygienists, ophthalmologists, general practitioners, or physical therapists. Although mental health treatments are sometimes treated as a taboo issue (rather than arthritis, a cavity, or a sprain) it is something that lots of people get benefit from. Some people may also believe that people should just “suck it up” and be strong on their own. This myth can be very damaging. While you should certainly do what you can to work on your emotions on your own, you can also benefit from someone else’s help. Certain disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder, can make it physically impossible for a person to deal with their emotions by themself. There is nothing weak about seeking counseling. It shows that you care about yourself. Most counselors and therapists cannot prescribe medicine. However, a trained mental health professional can know when it may be time to refer you to a specialist or medical doctor who can diagnose and prescribe medication for disorders like depression or anxiety.

High sensitivity may be depression or other issue. Some people are born very sensitive, and it is evident from babyhood. This is not a disorder, mental illness, or something "wrong"--it is a character trait. However, if a person goes from normal sensitivity to very sensitive, "touchy", "weepy", "irritable" or the like, that may be an indication that there is something not quite right. Sometimes high sensitivity is a result of depression, and causes a person to be overwhelmed with emotions (both negative and sometimes positive as well). Chemical imbalances can cause high emotional sensitivity. For instance, a pregnant woman may react very emotionally. Or a boy going through puberty. Or a person with a thyroid issue. Some medications or medical treatments can cause emotional changes. A trained medical practitioner should help screen you for depression. It is easy to self-diagnose, but in the end, you are best off with professionals who may be able to figure out if a person is depressed or highly sensitive due to other factors.

Be patient. Emotional growth is like physical growth; it takes time, and can feel uncomfortable while it is happening. You will learn through mistakes, which will have to be made. Setbacks or challenges are all necessary in the process. Being a very sensitive person is often more difficult as a youth than it is as an older adult. As you mature, you will learn to manage your feelings more effectively, and gain valuable coping skills. Remember, you have to know something really well before you can act on it, otherwise it is like heading into a new area after glancing at a map without understanding the map first - you don’t have enough understanding of the area to be able to travel it well and getting lost is almost certain. Explore the map of your mind, and you’ll have a better understanding of your sensitivities and how to manage them.

Comments

0 comment