views

X

Research source

Developing Your Topic

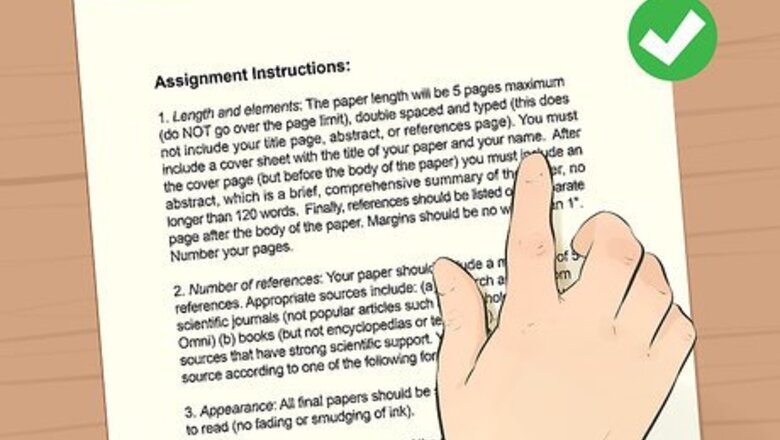

Read through your assignment instructions carefully. How much leeway you have to develop your research question depends on how tightly your assignment is structured. Make sure you understand what your instructor wants so you can find a topic you're interested in learning about that best suits the assignment. If you don't understand any aspect of the assignment, don't be afraid to ask your instructor directly. It's better to get an explanation about something than to assume you know what it means and later find out your assumption was incorrect.

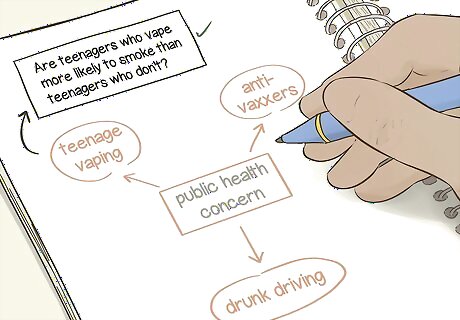

Brainstorm some topics that interest you and fall within the assignment's parameters. Typically, an instructor will provide a broad topic area, then expect you to find a more narrow topic to research that falls within that broad area. For example, suppose your instructor assigned a research paper about a "public health concern." You might make a list that included such public health concerns as teenage vaping, anti-vaxxers, and drunk driving. From your list, choose one area in particular that you want to look at. This is where you'll start your research. For the purposes of this example, assume you chose to research vaping among teenagers.

Look up general information about the topic. Once you've got an idea for a more narrow topic you want to focus on, do an online search to see generally what information is out there about it. At this point, pay attention to the amount of information available and the issues raised by some of that information. If you're doing a general internet search on your topic and not getting back many strong results, there may not be enough information out there for you to research that topic. This is typically rare, though, unless you've started off with a topic that's too narrow. For example, if you want to study vaping in your high school, you might not find enough sources. However, if you expanded your search to include all high schools in your state, you might have more luck. If you're not very knowledgeable about your topic, look for a resource that will provide a general overview, so you can become more familiar with possible questions you could answer in your research paper.

Decide on the question you want to answer through your research. After you've done a little preliminary research, you'll likely have some idea of the kinds of issues that are pressing in your chosen area. Form a question based on one of those issues that you can answer through research. For example, if you wanted to look at teenagers and vaping, you might decide to ask "Are teenagers who vape more likely to smoke than teenagers who don't?" How you frame your question also depends on the type of paper you're writing. For example, if you were writing a persuasive research essay, you would need to make a statement, and then back that statement up with research. For example, instead of asking if teenagers who vape are more likely to smoke than teenagers who don't, you might say "Teenagers who vape are more likely to start smoking."Tip: Be versatile with your research question. Once you start more in-depth research, you may find that you have to adjust it or even change it entirely, and there's nothing wrong with that. It's just part of the process of learning through research.

Seek knowledge about your specific question. At this point, you're ready to do some preliminary research based on the question you've chosen. It can help to type your exact question into the search engine, then go through the results you get. Look at the number of results you get, as well as the quality of the sources. You might also try an academic search engine, such as Google Scholar, to see how much academic material is out there on your chosen question.

Refine your question based on the information you find. You may find that your question is too broad or too narrow based on the number of potential sources you find. To adjust the scope of your question, look at "who," "when," and "where." For example, if you've selected teenagers who vape, the "who" would be teenagers. If a search of that topic yields too much information, you might scale it back by looking at a specific 5-year period (the "when") or only at teenagers in a specific state (the "where"). If you needed to broaden your question on the same topic, you may decide to look at teenagers and young adults under the age of 25, not just teenagers.

Finding Quality Sources

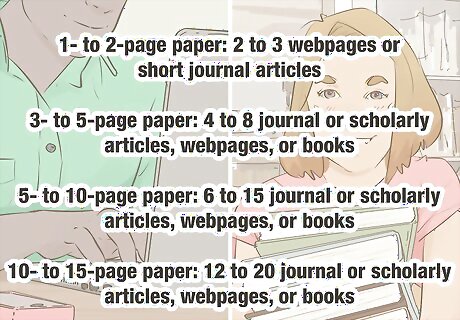

Identify the types of sources you'll likely need. The types of sources you'll use for your research depend on your grade level or education level. Generally, you can use short journal articles or webpages for a shorter paper. For a longer paper, you'll likely need to look at books and longer scholarly articles. While the requirements differ based on your assignment and the topic you're researching, you may find these guidelines helpful: 1- to 2-page paper: 2 to 3 webpages or short journal articles 3- to 5-page paper: 4 to 8 journals or scholarly articles, webpages, or books 5- to 10-page paper: 6 to 15 journals or scholarly articles, webpages, or books 10- to 15-page paper: 12 to 20 journals or scholarly articles, webpages, or books

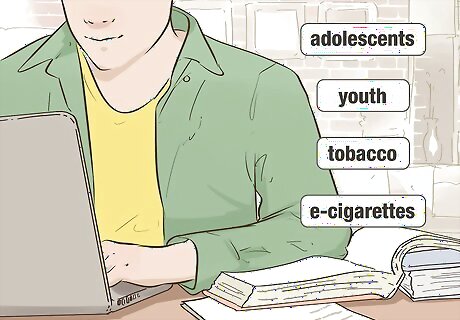

Use topical keywords to find your initial sources. The success of your research depends on searching the right keywords, especially in its initial stages. Brainstorm a list of keywords, including synonyms. For example, if you're researching the prevalence of vaping among teenagers, you might also include "adolescents" and "youth" as synonyms for teenagers, along with "tobacco use" or "e-cigarettes" as synonyms for vaping. Take advantage of academic databases available online through your school in addition to the internet.Tip: Get help from research librarians. They know the most efficient ways to find the information you need and may be able to help you access sources you didn't even know existed.

Evaluate potential sources using the CRAAP method. The letters stand for Currency, Reliability, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose/Perspective. This method provides you an easy way to quickly and uniformly evaluate the quality of potential sources you find by asking specific questions about the source: Currency: How recent is the information? When was the source last updated? Reliability: Are there references for facts and data? Is the content mostly opinion? Authority: Who is the creator of the content? Who is the publisher? Are they biased in any way? Does the creator have academic credentials in the field? Accuracy: Has the content been peer-reviewed or edited by a third party? Is the information supported by evidence? Can you easily verify facts in another source? Purpose/Perspective: Is the content intended to teach you something or to sell you something? Is the information presented biased?Tip: If your source fails any prong of the CRAAP method, use extreme caution if you refer to it in your research paper. If it fails more than one prong, you're probably better off not using it.

Mine reference lists to find additional sources you can use. When you find a good source for your topic, chances are that source cites other valuable sources that you can look up. The biggest benefit of this is that you don't have to do as much work evaluating the quality of these sources – the author of the source that cited them has already done that for you. If an author mentions a particular source more than once, you definitely want to read that material. The reference list typically contains enough information for you to find the source on your own. If you find that you can't access the source, for example because it's behind a paywall, talk to your school or a public librarian about it. They may be able to get you access.

Take notes about each resource you find. Using a set of index cards enables you to place each note on a separate card, which will make it easier for you to organize your notes later. There are also computer apps, such as Evernote, Microsoft OneNote, or Scrivener, that allows you to do this digitally. Some of these apps are free, while others require you to purchase a subscription. List the citation information for the source at the top of the card, then take notes in your words. Include the page numbers (if applicable) that you would use in your citation. If you copy something directly from the source, put quote marks around those words and write the page number (if applicable) where that quote appears. You may also want to distinguish quotes even further, for example, by having quotes in a different color text than your words. This will help protect you against accidental plagiarism.

Organizing Your Information

Create a spreadsheet with bibliographic information for all of your sources. A spreadsheet allows you to quickly organize and find the citation information for your sources as you work on your paper. Having this information ready allows for the least disruption of your writing process. Include columns for the full citation and in-text citation for each of your sources. Provide a column for your notes and add them to your spreadsheet. If you have direct quotes, you might include a separate column for those quotes. Many word-processing apps have citation features that will allow you to input a new source from a list, so you only have to type the citation once. With a spreadsheet, you can simply cut and paste.Tip: Even if your word-processing app automatically formats your citation for you, it's good practice to create the citation yourself in your spreadsheet.

Categorize your notes into groups of similar information. As you were taking notes, you likely grouped those notes by the source where you found them. Now, look at the information covered by each source and come up with categories of information. Then you can start stacking or grouping note cards together that fall into the same category. For example, if you were writing a paper on teenagers and vaping, you may have notes related to the age teenagers started vaping, the reasons they started vaping, and their exposure to tobacco or nicotine before they started vaping. If you used a digital note-taking app, you typically would categorize your notes by adding tags to them. Some notes may have more than one tag, depending on the information it covered.

Order your categories in a way that answers your research question. Look at your categories and try to formulate a logical order that answers your questions or tells the persuasive story that you want to tell through your research. You may have to rearrange them more than once to find the best fit. For example, suppose your research indicated that teenagers who vaped were more likely to switch to regular cigarettes if someone in their household smoked. The category covering teenage vapers' exposure to tobacco or nicotine before they started vaping would most likely be the first thing you talked about in your paper, assuming you wanted to put the strongest evidence first.

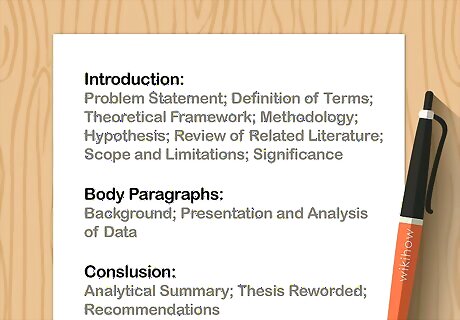

Draft a basic outline for your paper based on your order of categories. Now that you've put your categories in order, you're ready to create a rough outline of your paper. Keep in mind this may change when you start writing, but for now, it will give you a roadmap and help you identify any problems or weak spots in your research. Unless your instructor has specific requirements for your outline, you can make it as detailed or as simple as you want. Some people prefer full sentences in their outlines, while others have sections with just a word or two. Working through the outline methodically can help you identify information that you don't have yet that you need to support your thesis or answer your research question.

Review your notes and adjust your research question as necessary. As you researched, you may have found that you weren't asking the right question. You may also have found that there was more information available than you previously thought, and you need to narrow your focus. Even at this late stage, don't be afraid to change your question to more accurately frame your research. Because of your research, you know a lot more about the topic than you did when you first wrote your question, so it's natural that you would see ways to improve it.

Search for additional sources to fill holes in your research. When looking at your notes and outline, you may realize that some points are more well-supported than others. You may also find small issues that you hadn't noticed before that need to be addressed. For example, when outlining your paper about teenagers and vaping, you may realize that you don't have any information on how teenagers access e-cigarettes and whether that access is legal or illegal. If you're writing a paper about teenagers vaping as a public health concern, this is information you would need to know. It's also likely that as you formulated your outline, you discovered that you didn't need some sources you previously thought would be valuable. In that situation, you may need to seek more sources, especially if throwing out a source took you below the minimum number of sources required for your assignment.

Comments

0 comment