views

How to Get Started

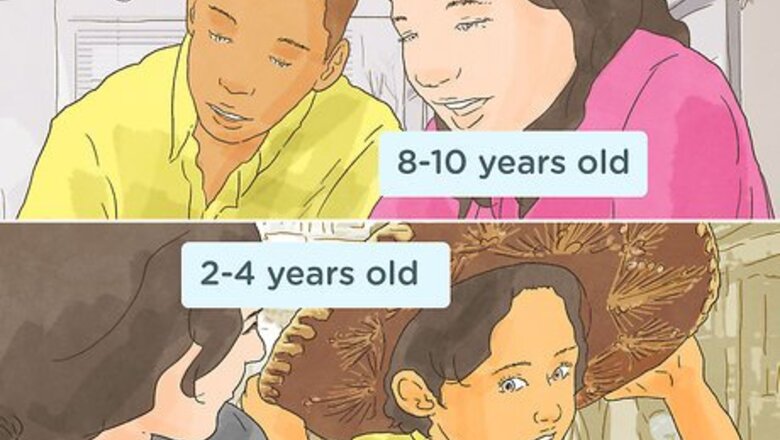

Identify the age group you are writing for. Children’s stories are often written with a specific age group in mind. Are you trying to write a story for toddlers? For older children? Identify if you are writing for children age 2-4, 4-7, or 8-10. The language, tone, and style of the story will change based on which age group you are writing for. For example, if you are writing for a 2-4 or 4-7 age range, you should use simple language and very short sentences. If you are writing for an 8-10 age range, you can use language that is a bit more complex and sentences that are longer than four to five words.

Use a memory from your childhood as inspiration. Think about memories of your childhood that were exciting, strange, or a bit wondrous. Use a memory as the basis for the children’s story. For example, maybe you had a strange day in third grade that you could turn into an entertaining story. Or perhaps you experienced a foreign country when you were very young and have a story from the trip kids would enjoy.

Take a common thing and make it fantastical. Pick an everyday activity or event and give it some whimsy. Make it fantastical by adding an absurd element to it. Use your imagination to try to view it as a child might. For example, you may take a common event like going to the dentist and make it fantastical by having the machinery used by the dentist come alive. Or you may take a child’s first time in the ocean and make it fantastical by having the child go into the deep depths of the ocean.

Pick a theme or idea for the story. Having a central theme for the story can help you generate ideas. Focus on a theme like love, loss, identity, or friendship from a child’s point of view. Think about how a child might view the theme and explore it. For example, you may explore the theme of friendship by focusing on the relationship between a young girl and her pet turtle.

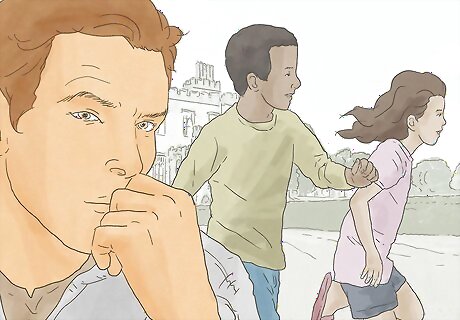

Create a unique main character. Sometimes a children’s story hinges on a main character that is relatable and unique. Think about character types that do not get represented often in children’s stories. Make your character particular by using real life qualities in children and adults that you find interesting. For example, you may notice that there is not a lot of children’s stories where a young girl of color is the main character. You may then create a main character that fills this void.

Give your main character one to two distinguishing traits. Make your main character stand out to readers by giving them unique physical traits such as a certain hair style, a particular style of dress, or a distinct walk. You can also give the main character personality traits like a kind heart, a love for adventure, or a tendency to get into trouble. For example, you may have a main character who always wears her hair in long braids and has an obsession with turtles. Or you may have a main character who has a distinct scar on her hand from that time she fell off a tree.

Create a set up. Plot out the story in six parts, starting with the exposition, or the set up. In the set up, you introduce the setting, the main character, and the conflict. Start with the name of the main character, and then describe a particular place or location. You can then outline the character's desire or goal, as well as an obstacle or issue they have to deal with. For example, you may have exposition like: a young girl named Fiona who wants a pet discovers a turtle in the lake by her house.

Have an inciting incident. This is the event or decision that changes or challenges the main character. The event or decision can come from another character. It can also come from an institution, such as a school or a job. Or it can come from nature, such as a storm or a tornado. For example, you may have an inciting incident like: Fiona’s mother says she cannot have a pet because it is too much responsibility.

Include rising action. The rising action is where you develop your main character and explore their relationship with other characters in the story. Show them living their life in the midst of the inciting incident. Describe how they cope or adjust to the inciting incident. For example, you may have rising action like: Fiona captures the turtle and hides it in her backpack, carrying it everywhere with her in secret so her mother does not find it.

Have a dramatic climax. The climax is the high point of the story, where the main character has to make a major decision or choice. It should be full of drama and be the most exciting moment in the story. For example, you may have a climax like: Fiona’s mother discovers the turtle in her backpack and tells her the turtle cannot be her pet.

Include falling action. The falling action is the point where the main character deals with the results of their choice. They may have to make amends or make a decision. The character may also join together with another character in this section of the plot. For example, you may have falling action like: Fiona and her mother get in an argument and the turtle escapes. They then both go in search of the turtle when they discover it missing.

End with a resolution. The resolution wraps up the story. It tells the reader whether the main character succeeds or fails to achieve their goal. Maybe your main character gets what they want. Or perhaps they make a compromise. For example, you may have a resolution like: Fiona and her mother discover the turtle in the lake and watch it swim away together.

Read examples of children’s stories. Get a better sense of the genre by reading examples of children’s stories that have been successful. Try to read stories that focus on the demographic or age group you’d like to write for. You may read: Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett

How to Create a Draft

Create an engaging opening. Start with a sentence that will hook the reader in right away. Use a strange image of the main character as the opening. Show the main character in action. The opening should set the tone for the rest of the story and let the reader know what to expect. For example, the first line of “The Beginning of Smoke” by Brunei Darussalam is: “At the beginning of the world, smoke was a man. At that time, there was a boy named Si Lasap, an orphan, who was constantly harassed by the village youths…” This opening establishes character, tone, and a fantastical element to “smoke.”

Use sensory language and detail. Make your characters come alive by focusing on what they see, smell, taste, touch, feel, and hear. Include language that describes the senses so your audience stays engaged in your story.. For example, you may describe a setting as “loud and bold” or “hot and sticky.” You can also use sounds like “crash,” “bam,” “bang,” or “whoosh” to make the story entertaining for your readers.

Include rhyme in the story. Grab your young reader’s attention by integrating rhyming words into your story. Try writing in rhyming couplets, where the end of every two lines rhyme. Or use rhyming in the same sentence, such as “he was hurly burly” or “she was rough and gruff.” You may use perfect rhyme, where the vowel and consonant sounds match. For example, “eat” and “sweet” would be a perfect rhyme. You can also use imperfect rhyme, where only the vowel or the consonant sound match. For example, “eat” and “leaf” would be an imperfect rhyme, as only the “ee” vowels match.

Use repetition. Help the language in your story pop by repeating key words or phrases throughout the book. Repetition can help keep your reader engaged and make the story stick in their minds. For example, you may repeat a question, such as, “Where did Dorothy the turtle go?” throughout the story. Or you may repeat a phrase like, “Oh no!” or “Today is the day!” to keep the pace and energy of the story moving.

Include alliteration, metaphor, and simile. Alliteration is where each word begins with the same consonant sound, such as “Anna an angry ant” or “Tutu the turtle tumbled.” It is a fun way to add rhythm to your writing and keep your story entertaining for kids. Metaphor is when you compare two things together. For example, you may include metaphors like, “The turtle is a green shell floating on the lake.” Simile is when you compare two things together using “like” or “as.” For example, you may include similes like, “The turtle is as wide as my hand.”

Have your main character deal with a conflict. The key element of a good story is conflict, where the main character must overcome an obstacle, a problem, or an issue to succeed. Limit your story to one conflict that is concrete and clear to readers. You may have a main character struggling with acceptance by others, with family issues, or with their physical growth. Another common conflict in children’s stories is fear of the unknown, such as learning a new skill, going to a new place, or getting lost. For example, you may have a main character who struggles to fit in at school, so she decides to make a turtle her best friend. Or you may have a main character who is afraid of the cellar in her house and has to learn to conquer her fears.

Make the moral of the story uplifting, but not preachy. Most children’s stories will have a happy, uplifting ending with a moral. Avoid making the moral feel too heavy handed. A subtle moral will be more effective and less obvious to your readers. Try showing the moral through the actions of your characters. For example, you show the young girl and her mother hugging by the lake as the turtle swims away. This could explore the moral of finding support through family without telling the reader the moral.

Get the story illustrated. Most children’s books come with illustrations that bring the story to life visually. Try illustrating it yourself or hire an illustrator. In many children’s books, the illustrations do half the work of getting the story across to the reader. You can include character details like clothing, hairstyle, facial expression, and color in the illustrations. In most cases, the illustrations for children’s books are created after the story is written. This allow the illustrator to draw based on the content in each scene or line of the story.

How to Polish the Story

Read the story aloud. Once you’ve finished a draft of the children’s story, read it aloud to yourself. Listen to how it sounds on the page. Notice if there is language that is too complicated or high level for your target age group. Revise the story so it is easy to read and follow.

Show the story to children. Get feedback from your target age group. Ask your siblings, your younger family members, or children at your school to read your story and give you feedback. Adjust the story so it is more appealing and relatable for children.

Revise the story for length and clarity. Go through the draft and make sure it is not too long. Often, children’s stories are the most effective when they are short and to the point. Most children’s stories have very little text, and when they do, they make the text count. Laurie Halse Anderson Laurie Halse Anderson, Young Adult Novelist Revise whenever you have a free moment. "I've written in every imaginable location; a repurposed closet, the kitchen table, the bleachers while my kids had basketball practice, the front seat of the car when they were at soccer. In airports. On trains. In the break room when I was supposed to be wolfing down dinner. In the back of classrooms when I was supposed to be paying attention."

Consider getting the story published. If you like your children’s story, you may submit it to publishers who consider children’s books. Create a query letter for your children’s story to send to editors and publishers. You can also try self-publishing your children’s book and selling it online to readers.

Comments

0 comment