views

Establishing the Purpose

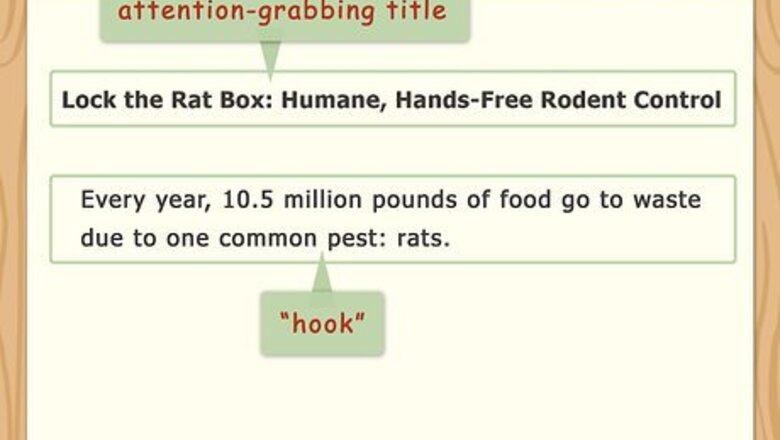

Grab your reader’s attention. Concept papers are meant to persuade sponsors, convincing them to fund or adopt your idea. This means it’s critical to “hook” them right at the beginning. For instance, you could start off your paper with an attention-grabbing statistic related to your project: “Every year, 10.5 million pounds of food go to waste due to one common pest: rats.” Giving your concept paper a descriptive title, like “Lock the Rat Box: Humane, Hands-Free Rodent Control,” is another good way to grab their attention.

Explain why you are approaching this sponsor. After getting your reader’s attention, the introduction to your concept paper should then describe how your goals and the sponsor’s mission mesh. This tells the sponsor that you’ve done your homework and are serious about approaching them. Try something like: “The Savco Foundation has long been committed to funding projects that foster healthy communities. We have developed Lock the Rat Box as an easy, cost-effective means to lower illness rates and sanitation costs in municipalities, and are seeking your support for the project.”

Describe the problem your project addresses. The next section of a concept paper will devote a few sentences or short paragraphs to the specific purpose of your project. Describe the problem you want to solve, and illustrate how you know it exists.

Put the problem in context to explain why it matters. Show how your project relates to current issues, questions, or problems. Statistics and other numerical data can help build a convincing case for why your problem matters. Some readers might also be moved by narratives or personal stories, so consider including those as well. For instance, your concept paper could include a statement like: “Rats are a nuisance, but also a serious vector of diseases such as rabies and the bubonic plague. Municipalities across the United States spend upwards of twenty million dollars a year combating these issues.” Include references to verify any data you cite.

Explaining How your Concept Works

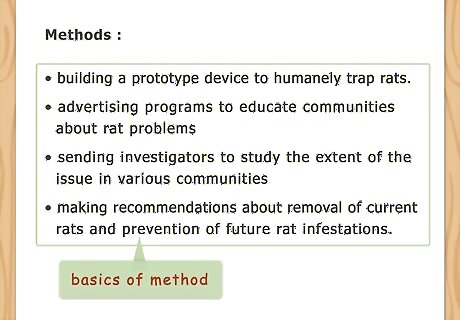

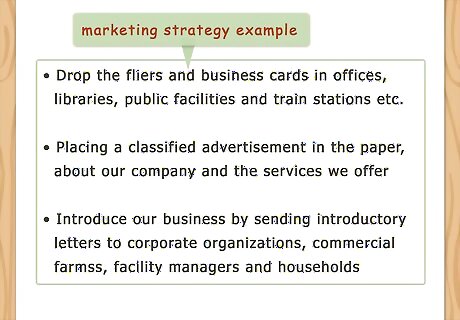

Share the basics of your method. Even if readers are convinced you have identified an issue that matters, they’ll still want to know that you have an idea for how to solve or investigate it. Spend some time in your concept paper describing the methods you will use. For instance, your project may involve building a prototype device to humanely trap rats. Your methods might also involve activities. For instance, you may propose advertising programs to educate communities about rat problems, or sending investigators to study the extent of the issue in various communities.

Emphasize what makes your methods unique. Remember that sponsors may be looking at numerous requests for funding. To ensure that yours is successful, you have to explain what sets your project apart. Ask yourself the question: “What is my project doing that no one has done or tried before?” Try using statements like: “While previous governmental services have explained rat infestations via poster, radio, and television campaigns, they have not taken advantage of social media as a means of connecting with community members. Our project fills that gap.”

Include a timeline. You can’t expect a donor or foundation to be willing to fund a completely open-ended project. Part of your concept paper should explain the projected timeline for implementing your project. For example: “February 2018: sign a lease for a workshop space. Late February 2018: purchase materials for Lock the Rat Box prototype. March 2018: conduct preliminary tests of the prototype.”

Give concrete examples of how you will assess your project. Sponsors want to fund projects that are likely to succeed, and part of your job in the concept paper is to explain how to measure your project’s outcomes. If you are developing a product, for example, that success can be measured in units produced and/or sold. Other assessment tools could include things like surveys to gauge customer satisfaction, community involvement, or other metrics.

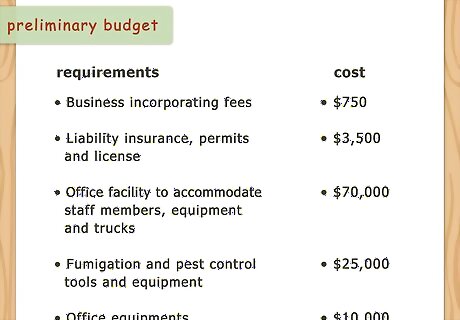

Provide a preliminary budget. Sponsors will be interested to see a general overview of how much your project is expected to cost. This explains the need for funding and helps the sponsor determine if the project’s scope is appropriate. A concept paper is a preliminary proposal, so not every detail needs to be spelled out, but give info on the basics of costs that may include things like: Personnel, including any assistants Equipment and supplies Travel Consultants you may need to bring in Space (rent, for example)

End with a project summary. Wrap things up with a short paragraph at the end of your paper, reiterating your project’s purpose, basic plan of action, and needs. Focus on the essential points you want to stick in the sponsor’s mind.

Reviewing the Draft

Keep it short and neat. Concept papers are typically short documents of 3-5 double-spaced pages. Sponsors may have many applications to read, and a concept paper that drags on or is poorly formatted might get rejected outright. If the application requests a particular format, follow the directions exactly. Otherwise, type your paper in a standard font at a readable size (12 point is good), number your pages, and use reasonable margins (1 inch all around is fine).

Check that the language of your concept paper is action-oriented. Sponsors are looking for projects that are well-thought out and doable. Avoid hedging your proposal or doing anything that sounds like you aren’t completely confident in your project. For instance, avoid statements like “We believe that our product, Lock the Rat Box, could potentially help certain municipalities at least control rat infestations.” A stronger statement would be: “Lock the Rat Box will curtail rat infestations in any mid-sized municipality, and completely eradicate them in many cases.”

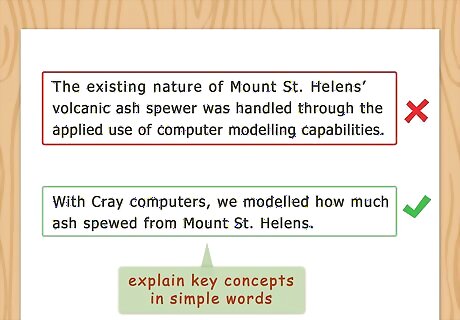

Use vocabulary that your reader will understand. For instance, if you are writing to a scientific foundation for funding, it may be appropriate to use technical terminology. However, writing to a general community organization to fund the same project will require you to reduce scientific jargon and explain key concepts so that general readers will understand. If you are writing for a general, non-expert audience, ask someone unfamiliar with your project to read your concept paper and tell you if there were any parts they did not understand.

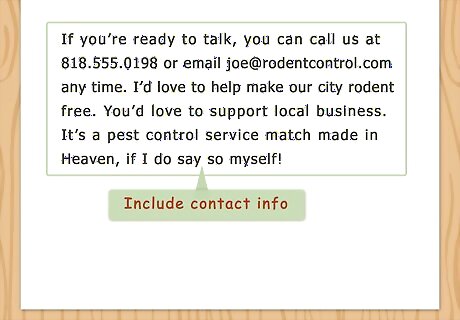

Include contact info. Make sure the sponsor knows how to reach you by mail, email, and phone. Even if you’ve included this information elsewhere in a project application, it’s a good idea to include it in the concept paper so the sponsor won’t have to hunt for it.

Proofread your final draft. An otherwise strong concept paper riddled with errors, typos, or formatting mistakes will reflect poorly on your project. Show the sponsors that you are careful, thoughtful, and appreciative by polishing your final draft before submitting. Have someone who has not previously read your concept paper take a look at the final draft before you submit it. They’ll be more likely to catch any lingering errors.

Comments

0 comment