views

X

Research source

You can easily find IPA spellings of most words in a dictionary or with a web search. In order to interpret IPA spellings, you will need to get familiar with phonetic writing. You can use phonetic writing to record the pronunciation of words you aren’t familiar with, like words from foreign languages. But before you do, you'll have to master the symbols for the major classes of common sounds: plosives, nasals, fricatives, approximants, taps, flaps, and vowels.

Perfecting Vowels

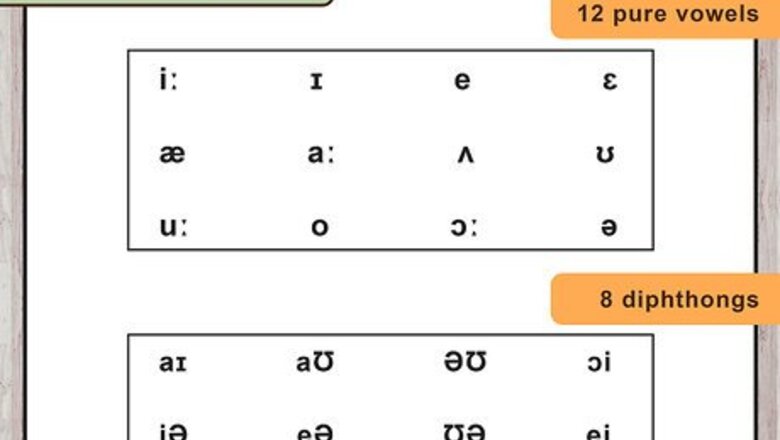

Figure out vowel features. All vowels are voiced. Vowels are defined by the height of the tongue in the mouth (high, mid, low) and its position with regard to the lips (front is towards the lips, back is away). The tension in muscles when the sound is made (tense or lax) and rounding of the lips (rounded or spread) are also significant when distinguishing one vowel from another. In the Received Pronunciation accent of English, there are 12 pure vowels and 8 diphthongs (also called gliding vowels). Vowels are spoken with an unobstructed vocal tract. When making a vowel sound, your tongue should not touch your lips, teeth, or roof of the mouth.

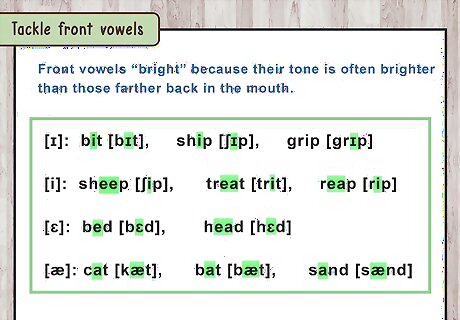

Tackle front vowels. Front vowels are generally described as “bright” because their tone is often brighter than those farther back in the mouth. The IPA lists over 12 potential front and near-front vowels. The four most common American English front vowels follow: [ɪ]: “bit” [bɪt], “ship” [ʃɪp], “grip” [grɪp] [i]: “sheep” [ʃip], “treat” [trit], and “reap” [rip] [ɛ]: “bed” [bɛd], “head” [hɛd], “instead” [ɪnstɛd] [æ]: “cat” [kæt], “bat” [bæt], “sand” [sænd]

Master central position vowels. The IPA distinguishes three central position vowels in General American English. Each central vowel requires the tongue to be approximately halfway between a front or back vowel. Use the following symbols for central vowels: [ɜ:]: “curve” [kɜ:rv], “bird” [bɜ:rd], “stir” [stɜ:r] [ə]: “syllable” [sɪləbəl], “moment” [momənt], “felony” [fɛləni] [ʌ]: “cut” [kʌt], “glove” [glʌv], “gun” [gʌn]

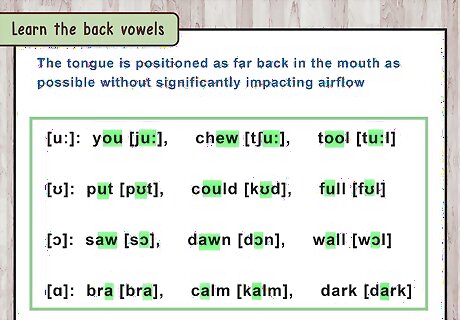

Learn the back vowels. When making a back vowel, the tongue is positioned as far back in the mouth as possible without significantly impacting airflow. Opposite of front vowels, these are frequently called “dark vowels” because of their darker sounding tone. American English has the following four back vowels: [uː]: “you” [ju:], “chew” [tʃu:], “tool” [tu:l] [ʊ]: “put” [pʊt], “could” [kʊd], “full” [fʊl] [ɔ]: “saw” [sɔ], “dawn” [dɔn], “wall” [wɔl] [ɑ]: “bra” [bra], “calm” [faðər], “dark” [dark]

Commit diphthongs to memory. Diphthongs combine 2 different vowel sounds in the same syllable. Separate vowels frequently get absorbed into a single diphthongized sound when people speak quickly. American English uses the following diphthongs: [eɪ]: “wait” [weɪt], “pray” [preɪ], “say” [sei] [aɪ]: “like” [laɪk], “sight” [saɪt], “pie” [paɪ] [ɔɪ]: “coin” [kɔɪn], “oil” [ɔɪl], “voice” [vɔɪs] [aʊ]: “mouth” [maʊθ], “found” [faʊnd], “count” [kaʊnt] [oʊ]: “show” [ʃoʊ], “boat” [boʊt], “coat” [koʊt]

Using Plosives

Identify the features of plosives. Also known as a stop or an oral occlusive, a plosive is a consonant that blocks and cuts off airflow when making its sound. This blockage is sometimes done by the tongue, though this may also happen in a part of the throat called the glottis. Plosive sounds, and many other classes as well, like fricatives, are usually divided into pairs of voiced (v+) and unvoiced (v-) sounds. The only difference between the 2 is that voiced sounds, like [b], cause the throat to vibrate, whereas unvoiced sounds, like [p], do not.

Learn the usage for the plosives [p] and [b]. These sounds are bilabial, which means they’re made with the lips. The [p] sound is unvoiced, and [b] is voiced. Examples of [p] include the words “pet” [pɛt], “pea” [pi], and “lip” [lɪp]. Examples of [b] include “boat” [boʊt], “bet” [bɛt], and “trouble” [trʌbəl].

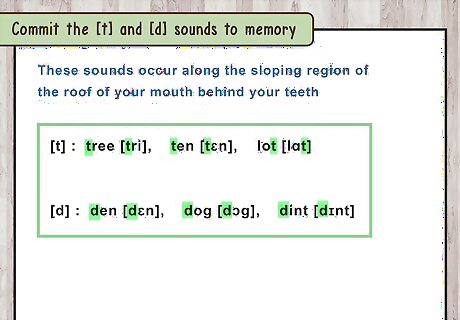

Commit the [t] and [d] sounds to memory. These sounds occur along the sloping region of the roof of your mouth behind your teeth. [t] is unvoiced and [d] is voiced. The [t] sound occurs in words like “tree” [tri], “ten” [tɛn], and “lot” [lɑt]. Words that use the [d] sound include “den” [dɛn], “dog” [dɔg], and “dint” [dɪnt].

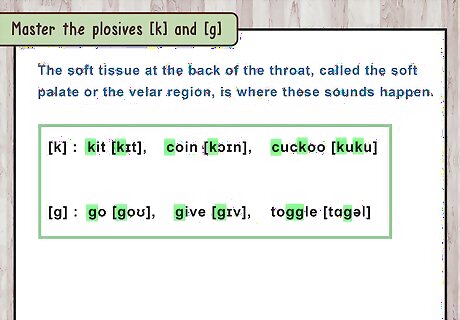

Master the plosives [k] and [g]. The soft tissue at the back of the throat, called the soft palate or the velar region, is where these sounds happen. The unvoiced sound in this pair is [k], while [g] is voiced. Words that use [k] sounds include “kit” [kɪt], “coin” [kɔɪn], and “cuckoo” [kuku]. Words that exemplify [g] include “go” [goʊ], “give” [gɪv], and “toggle” [tɑgəl].

Using Nasals and Flaps

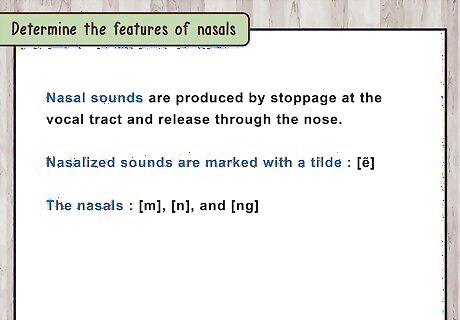

Determine the features of nasals. Nasal sounds show up a lot in Hindi, Portuguese, and French. Nasal sounds are those made where the soft tissue (vellum) at the back of the throat lowers. This allows air to move through the nose as sound is made, nasalizing the tone of the sound. All nasals described in this section are voiced, though some could potentially be unvoiced. Some languages have nasalized vowels or consonants. These are usually marked by a special symbol called a diacritic. Nasalized sounds are marked with a tilde (~) above the sound symbol, as in [ẽ]. Some languages may not have a large pool of nasal sounds. For example, the sound used to represent "-ing," [ŋ], is relatively uncommon when compared to other nasal sounds, like [m] or [n].

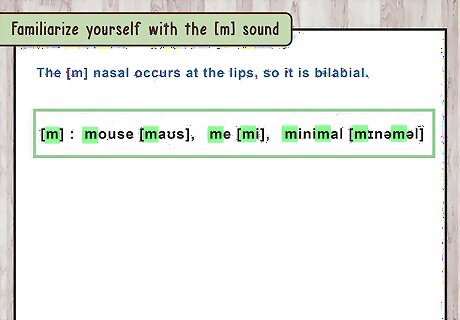

Familiarize yourself with the [m] sound. The [m] nasal occurs at the lips, so it is bilabial. The soft tissue at the back of the throat lowers and air passes through the nasal cavity when this sound is made. Some examples of the [m] sound include “mouse” [maʊs], “me” [mi], and “minimal” [mɪnəməl].

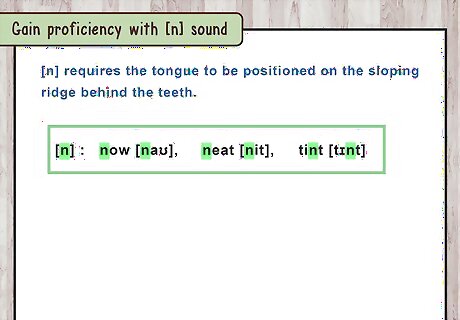

Gain proficiency with [n] sound. The [n] sound is similar to the [m] sound, but unlike [m], which is bilabial, [n] requires the tongue to be positioned on the sloping ridge behind the teeth. Words using [n] include “now” [naʊ], “neat” [nit], and “tint” [tɪnt].

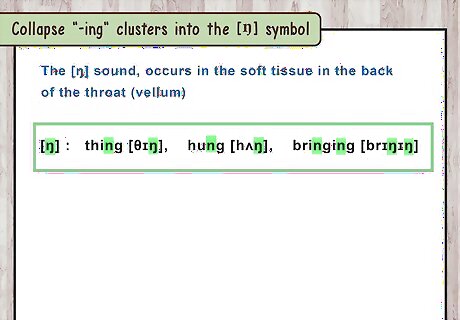

Collapse "-ing" clusters into the [ŋ] symbol. The [ŋ] sound, also called eng or engma, occurs in the soft tissue in the back of the throat (vellum). This sound is relatively rare among language families. Examples of [ŋ] include “thing” [θɪŋ], “hung” [hʌŋ], and “bringing” [brɪŋɪŋ].

Understanding Fricatives

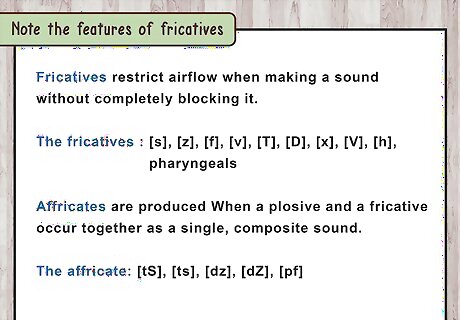

Note the features of fricatives. Fricatives make up the largest class of sounds. Fricatives restrict airflow when making a sound without completely blocking it. They are generally divided into 2 main types: sibilants and non-sibilants. Lateral fricatives, though related to normal fricatives, are distinguished from them and usually called by the term "affricate." In some situations, the terms “spirant” and “strident” may be used as a synonym for the word “fricative.”

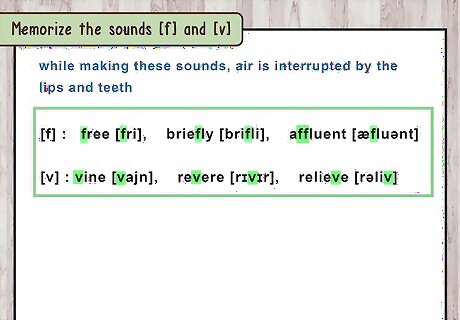

Memorize the sounds [f] and [v]. These sounds occur in the front of the mouth. Air is interrupted by the lips and teeth, which is why these are referred to as labiodental. The voiced member of this pair is [v]. Some examples of [f] include “free” [fri], “briefly” [brifli], and "affluent" [æfluənt]. Examples of [v] can be found in words like “vine” [vajn], “revere” [rɪvɪr] and “relieve” [rəliv].

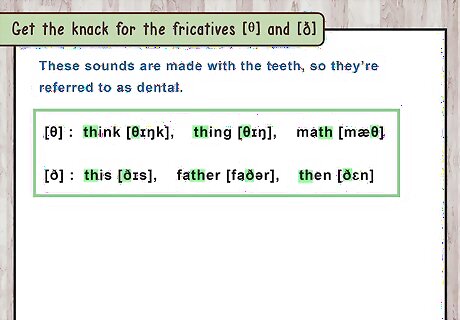

Get the knack for the fricatives [θ] and [ð]. These sounds are made with the teeth, so they’re referred to as dental. [θ], frequently called theta, is unvoiced. [ð], referred to as eth, is voiced, though in normal English writing, both sounds are usually represented by the letters “th.” Some examples follow: [θ]: “think” [θɪŋk], “thing” [θɪŋ], “math” [mæθ] [ð]: “this” [ðɪs], “father” [faðər], “then” [ðɛn]

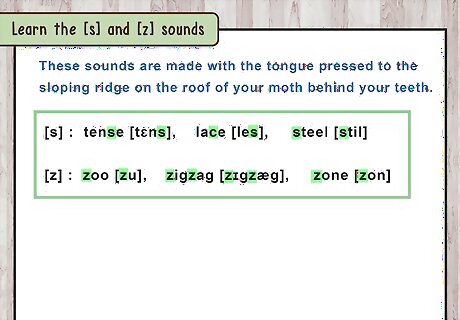

Learn the [s] and [z] sounds. This pair of sounds is one of the most common in human languages. [s] is unvoiced and [z] is voiced. Both sounds are made with the tongue pressed to the sloping ridge on the roof of your mouth behind your teeth. The [s] sound can be found in words like “tense” [tɛns], “lace” [les], and “steel” [stil]. Look for [z] in words like “zoo” [zu], “zigzag” [zɪgzæg], and “zone” [zon].

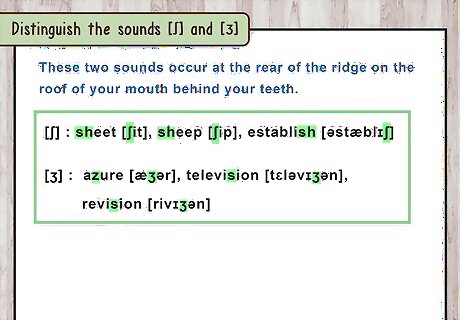

Distinguish the sounds [ʃ] and [ʒ]. These two sounds occur at the rear of the ridge on the roof of your mouth behind your teeth. [ʃ] is unvoiced and [ʒ] is voiced. [ʃ] can be found in such words as “sheet” [ʃit], “sheep” [ʃip], and “establish” [əstæblɪʃ]. Voiced examples of [ʒ] can be found in words like “azure” [æʒər], “television” [tɛləvɪʒən], and “revision” [rivɪʒən].

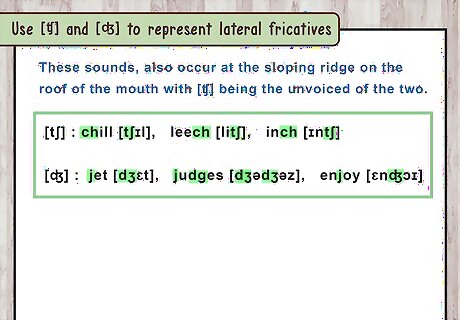

Use [ʧ] and [ʤ] to represent lateral fricatives. These sounds, much like [s] and [z], also occur at the sloping ridge on the roof of the mouth with [ʧ] being the unvoiced of the two. For examples of [tʃ], look to to words like “chill” [tʃɪl], “leech” [litʃ], and “inch” [ɪntʃ]. For examples of [ʤ], take a look at “jet” [dʒɛt], “judges” [dʒədʒəz], and “enjoy” [ɛnʤɔɪ]. It is common for sounds in this class to be called “affricates.” The key feature of affricate sounds is a brief stop followed by the release of that stop.

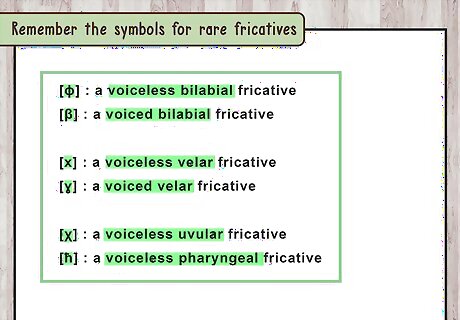

Remember the symbols for rare fricatives. There are many other kinds of fricatives, some of which might only exist in a few specific languages. The sound [h], as in “hat” [hæt], is considered a pseudo fricative, though it is listed with common fricatives. Some other fricative symbols you might see include: [ɸ], a voiceless bilabial fricative. [β], a voiced bilabial fricative. [x], a voiceless velar fricative. [ɣ], a voiced velar fricative. [χ], a voiceless uvular fricative. [ħ], a voiceless pharyngeal fricative.

Distinguishing Approximants

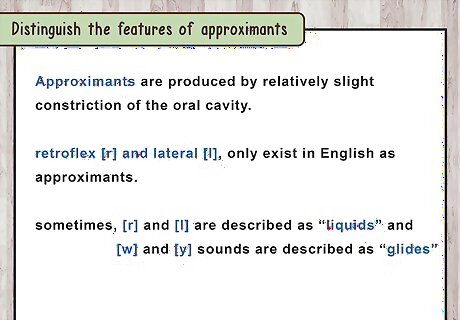

Distinguish the features of approximants. Approximants transition between articulators like the lips, tongue, and teeth. This creates air turbulence when making the sound. 2 common sound classes, retroflex [r] and lateral [l], only exist in English as approximants. In some situations, you may hear [r] and [l] described as “liquids” and [w] and [y] sounds described as “glides.” Instances where the [r] or [l] sound are made by a tap of the tongue on the roof of the mouth are sometimes called taps or flaps, like in the words “pity” and “water.” Some languages utilize trills where an articulator, like the tongue, vibrates when producing sound. Trills are considered distinct from taps and flaps.

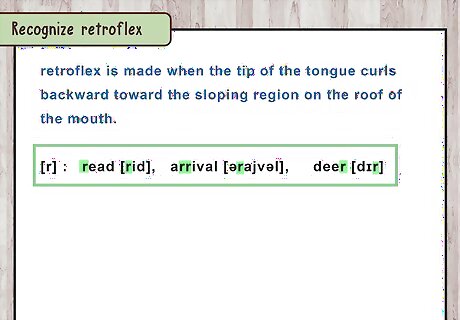

Recognize retroflex. Sometimes retroflex is written as [r] and other times as [ɹ]. The English retroflex approximant is made when the tip of the tongue curls backward toward the sloping region on the roof of the mouth. Some words that use this sound include “read” [rid], “arrival” [ərajvəl], and “deer” [dɪr].

Learn about laterals. Any sound that is made when air passes on the side of tongue is a lateral. There is only 1 lateral in English, which is also an approximant: [l]. Some words that employ this lateral include “leaf” [lif], “relax” [rəlæks], and “curl” [kərl].

Close out approximants with [w] and [j]. These sounds can also be called semivowels or glides. Both [w] and [j] are voiced. [w] requires lip rounding and a raising of the soft tissue at the back of the throat. When making the [j] sound, the tongue approaches the hard, smooth portion of the roof of your mouth. For examples of [w], look at “will” [wɪl], “towel” [tawəl], “owl” [awl]. For examples of [j], look at “yes” [jɛs], “toy” [tɔj], and “envoy” [ɛnvɔj].

Comments

0 comment