views

The Bombay of 1980s, among many other things, was known for its dancing girls. In their dark and dingy quarters, the so called world of sleaze, they ruled the world they had created.

Meena danced to De De Pyaar De. Geeta danced to Mere Haathon Mein Nau Nau Choodiyan Hain. Jhumki danced to Tuney O Rangeele Kaisa Jaadu Kiya. Renu danced to Nainon Mein Sapna. Rekha danced to Jawaani Jaaneman.

The dancing girls or women of the kothas in Congress House – an enclave of seven buildings surrounded by a mujra complex in Mumbai – had no one heroine to emulate in the 1980s when hit film songs began to take on an upbeat disco tempo, making the lithe-limbed dancers miss quite a few steps in their tightly wrapped sequined saris. It also marked a full-circle turn from traditional mujra performances to the disco mujra that set the standard for dance bars like Topaz to follow in Mumbai.

The kotha was once considered a celestial space where the enigmatic nautch girl lived in purdah, from where she commanded respect and a hefty fee for her vocal and kathak performances in royal darbars (courts). A zeitgeist was on the horizon; a mix of shimmering Bollywood dance moves had arrived. Flashy gold coins turned into crisp currency notes, and graceful glances were eclipsed by carnal winks.

The 80s was also the beginning of the end, when the dancing women slipped into prostitution with equal ease and wiped out the nawabi culture that kothas served – where were the nawabs to serve, most importantly, where was the nawabi luxury of “paisa phenk tawaif dekh”?

Women were dancing for handouts; the jewellery was rolled gold, anklets were cheap metal and squalid tenements housed seedy kothas. The nautch women were also competing with something even more sinister than unprotected sex in these dingy chawl-like quarters – television. The opening of the economy in the early 1990s led to a wide array of entertainment to choose from. MTV – a channel specialising in music, reality, and youth culture programming – revamped the mujra into a pool-side party where the groovy dance moves were only incidental.

The imperturbable countenance of the old-style courtesan became rigidly unfashionable. Regular patrons of the kothas in Grant Road and Foras Road got easily fatigued of the thumris, ghazals, and dadras sung by the ageing courtesans who sat still, immovable as a mountain, chewing paan and crooning one complicated taan after another. A musician trio comprising a tabla player, a harmonium player, and a sarangi player sat behind the songstress. The billowing silk sari she was enveloped in provided cover as they tried to tune their instruments to follow the singing diva’s meandering alaap. The whole scenario was a picture-perfect postcard of a bygone era being sucked up by depravity.

In a nebulous atmosphere such as this, where shifty ideals replaced shifting idols, who did the younger nautch women look up to? Not their predecessors, not the heroines of kotha-dramas, not even the disco queens like Parveen Babi, Zeenat Aman, Sridevi and Salma Agha.

Each survivor was her own hero, heroine, and martyr. If a nautch girl found a man who promised more than a fatal attraction, she disappeared with him, never to be heard of again. If that did not happen, as her business nosedived, she walked over to Kamathipura in her kitten heels and peddled flesh instead of tunes. The indignity was the same in both professions, she had nothing to lose, only to gain by switching, taking care of herself, and her family.

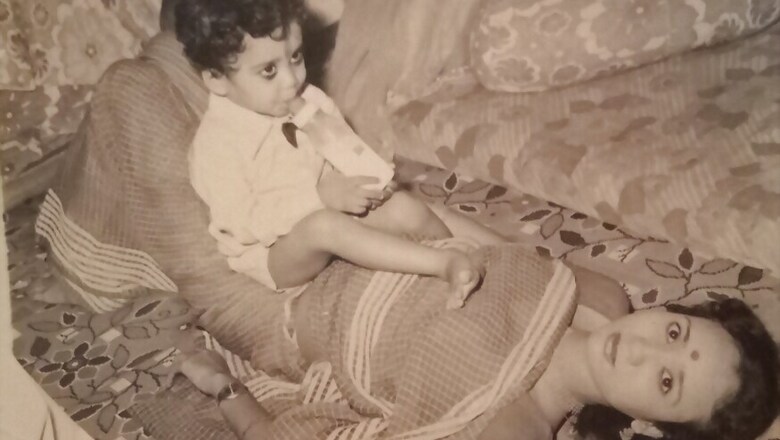

My mother, a child-bride from the Kanjarbhat community in Pune, found herself in a kotha in Kolkata when she reached puberty, because her husband and in-laws thought it would suit her when they tried to sell her off in a brothel in Sonagachi and could not pass her off as a virgin. She was given training in kathak and her vocal chords were stretched to sing ghazals. She had no prior knowledge of such things, having lived so far as a shepherdess on the moor.

She had never idolised anyone before. She reached the kotha because she had previously lived in abject poverty, where dreaming is considered rich and labour is life. An appreciation of the performing arts made her envious of the dancing skills of Helen and Vyjayanthimala. Muqabla Hum Se Na Karo, from the film Prince (1969), became her go-to video on television to imitate her two favourites. In the dance face-off, the legendary actresses express their fleet-footedness with such flair and joy that it is infectious. So much so, that for my mother the song ricochets her own struggle – don’t compete with me, I am trying to be the best version of myself.

#BeingAWoman is a special series to celebrate womanhood in today’s India on the occasion of International Women’s Day 2018

(Author is a reporter currently freelancing for The Hindu and has previously worked at Scroll.in and Midday. His first book Lean Days, a travel-fiction roman-a-clef (which incidentally has no kotha story) is being published by HarperCollins this month.)

Comments

0 comment