views

New Delhi: Out in the sub-urban areas of Maharashtra, away from the densely populated city of Pune, The Eco Factory Foundation, a non-profit making organization is partnering with agricultural trainers and local NGOs in providing practical knowledge to farmers and agricultural labourers in waste-management and sustainable farming.

Locals claim that their wages and chances of finding employment in farm lands across the area spike post the certification course.

In a first in India, the firm has also created a ‘Waste Management Park: Awareness and Learning Centre’ exhibiting different techniques of waste management which are applicable at individual, community as well as industrial level.

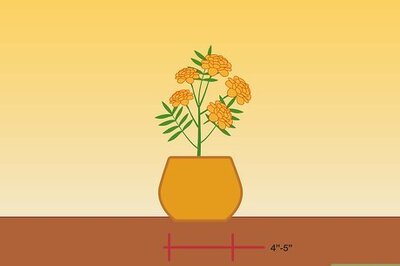

The foundation has also initiated a concept of creating ‘Edible Landscape at Campus Level’ in integration with the waste generated at campus level in various schools, colleges and other organizations such as Gokhale Institute Pune, SNDT Institute of Home Science Pune, among others along with launching training centre for the local farmers.

“These days everybody is moving towards a more organic future. Be it packed food, vegetables, soaps, beauty products or clothes, people are moving towards less chemically intensive techniques to have a healthier lifestyle. That is where The Eco Factory Foundation comes into picture,” said Anand Chordia, founder of the firm.

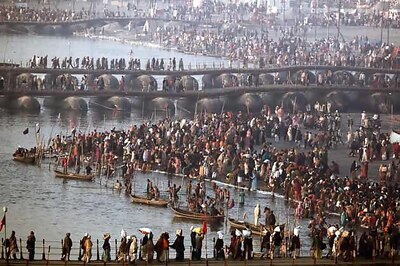

In 1951, the ‘landless agriculture labour’ numbered just 27.3 million which went up to 144.3 million (or 14.4 crore) in 2011. The Socio-Economic and Caste Census of 2011, which acknowledged and counted landlessness as a major indicator of poverty, put the ‘households with no land’ at 56.41 percent of total rural households or 101 million households. With a mean household size of 4.9 in rural India (as per the 2011 Census), the number of landless comes to 494.9 million (or 49.49 crore).

In 2009, the rural development ministry’s committee on State Agrarian Relations and Unfinished Task of Land Reforms pointed out that landlessness had witnessed a phenomenal rise from about 40% in 1991 to about 52% in 2004-5. It explained why: “While all the enhanced landlessness cannot be attributed to the liberalisation process alone, the non-agricultural demands placed on land on account of industrialisation, infrastructural development, urbanisation and migration of the urban rich in the rural areas have certainly contributed to the process.”

It also explained why landlessness has gone out of economic consciousness: “The post-liberalisation era has been marked by a debate. There is the view that the possibilities of Land Reforms have exhausted and future growth is only to come from private investment in the rural areas. The protective legislation act as an inhibiting factor to this investment. Accordingly, many states are proceeded to revise their legislation. Even within the government there was the view that distributive justice programmes have been overtaken by development paradigm.”

This committee was set up when the Maoist violence was at its peak with 220 districts (one-third of the total) declared as ‘Maoist-affected’ by the then Planning Commission of India.

There is no official assessment of how many became landless because of all the factors listed above but the report quoted eminent sociologist Walter Fernandes’ study to peg the figure of people disposed of their land at 60 million during the period of 1947 to 2004, involving 25 million ha of land. The report particularly referred to the alienation of tribal land as “the biggest grab of tribal lands after Columbus” in which the state was held complicit. It considered alienation of land and other critical natural resources to be at the root of the social unrest and violence in the Maoist-affected areas.

The NSSO data shows that the average landholding (including landless) in rural India has gone down from 1.53 ha in 1971-72 to 0.59 ha in 2013 — it halved between 1992 and 2013 — and 92.8 percent of rural households own less than 2 ha each. It also reflects another disturbing phenomenon -- marginalisation of rural landholdings. The larger landholdings of 1 to 10 ha or more are gradually shrinking since 1971-72 with more and more households falling into the marginal category (0.002- 1 ha).

The 2013 draft National Land Reform Policy provides the answer: “Landlessness is a strong indicator of rural poverty in the country. Land is the most valuable, imperishable possession from which people derive their economic independence, social status and a modest and permanent means of livelihood. But in addition to that, land also assures them of identity and dignity and creates condition and opportunities for realizing social equality. Assured possession and equitable distribution of land is a lasting source for peace and prosperity and will pave way for economic and social justice in India.”

“The foundation believes in ‘Waste to Wealth’ and ‘Waste to Health’ approach. It wants to address issues of Malnutrition and Food Security with creation of food forest with sustainable development in mind,” added the founder.

Comments

0 comment