views

Struggling to make significant progress against Moscow, Western countries and Ukraine are fervently attempting to apprehend Russian President Vladimir Putin. Their pursuit is driven by what they perceive as war crimes committed by him during the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict.

These nations are counting on the charges filed by the International Criminal Court (ICC) against Putin and Russian official Maria Lvova-Belova. The accusations stem from the alleged forcible deportation of thousands of Ukrainian children to Russia. Russia too hasn’t denied the claim and instead said that it has been ‘saving’ children from Ukraine’s own army and not stealing them.

Besides, some of the Western leaders are also highlighting an ongoing online campaign demanding Putin’s arrest when he lands in South Africa in late August this year for the BRICS Summit.

The campaign already signed by over half a million people and addressed to South African President Cyril Ramaphosa and to all members of the ICC reads: “Your authorities must arrest Putin if he sets foot on your territory, so he can be held accountable for the heinous war crimes he has committed, including the abduction and deportation of Ukrainian children.”

“Whatever happens, August will represent a fork in the road. Either Putin attends the BRICS summit, risking arrest, or by staying away he exposes his fear of being arrested. Whichever outcome, a line will be crossed,” wrote former UK prime minister Gordon Brown in The Guardian besides calling for “upfront American engagement” in the due process.

South Africa is a signatory to the Rome Statute, the ICC’s founding document, and therefore will be obligated to obey the ICC’s arrest warrant against the Russian president. Interestingly, the other major parties involved in the conflict, namely Ukraine, the US, and many NATO nations besides Russia, have not ratified it.

However, following the invasion of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine granted jurisdiction to the ICC over its territory and has hosted ICC prosecutor Karim Khan multiple times since the start of the current investigation a year ago.

It’s not that South Africa may walk a complex diplomatic tightrope for the first time. In 2015, the country made headlines by refusing to arrest then-visiting Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir who was subject to two ICC warrants charging him with genocides, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Pretoria had based its decision on the belief that African nations were being disproportionately targeted by the ICC.

But with superpowers in the ring this time, the situation for the Ramaphosa government could be tricky, a reflection of which was seen last month when the South African president announced his country’s withdrawal from the ICC to quickly make a U-turn with his office saying there was an “error in a comment made during a media briefing”.

According to a recent report in the Sunday Times, a South African government official was quoted saying that they have no option to not arrest Putin. “If he comes here, we will be forced to detain him,” the outlet reported.

Further, President Ramaphosa has set up a dedicated commission led by his vice president to examine the ICC arrest warrant. South African officials are actively engaging with the Kremlin in an attempt to dissuade Putin from visiting their country, thus aiming to avoid facing a difficult choice, the Times reported.

The issue has also become thorny in South Africa’s domestic political circle. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) secretary-general Fikile Mbalula in a recent interview with the BBC came out strongly in Putin’s support, questioning Britain’s position on the issue. “If it were according to the ANC, we would want President Putin here even tomorrow…We will welcome him to come here as part and parcel of BRICS, but we know that we are constrained by the ICC in terms of doing that. Putin is a head of state; do you think that a head of state can be arrested anywhere? Have you arrested Tony Blair…Where are the weapons of mass destruction?” Mbalula questioned.

The ANC shares strong ties with Moscow, stemming from the Soviet Union’s historical support for the party’s campaign against the white minority rule of Apartheid. While Kyiv also backed the ANC’s fight for democracy, Pretoria has thus far remained neutral and refrained from condemning the Russian invasion.

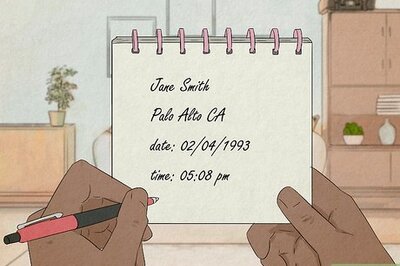

The arrest warrants issued by the Pre-Trial Chamber II of the Hague-based ICC against Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova on March 17 this year accused them of “war crime”. The release issued by the court read that the Russian president is “allegedly responsible for the war crime of unlawful deportation of population (children) and that of unlawful transfer of population (children) from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation (under articles 8(2)(a)(vii) and 8(2)(b)(viii) of the Rome Statute). The crimes were allegedly committed in Ukrainian occupied territory at least from 24 February 2022(the day war began).”

Identical charges were read out against Belova who is Commissioner for Children’s Rights in the Office of the Russian President.

Aside from that, the court chamber, in a strongly worded judgement, stated that although it could have kept the warrant confidential in order “to protect victims and witnesses and to safeguard the investigation,” it was compelled to make it public to prevent the “further commission of crimes”.

In a retaliatory move, Moscow issued an arrest warrant against Karim Khan, the British prosecutor at the ICC who had been persistently pursuing the “war crime” case in Ukraine.

The charges against Khan reportedly accuse him of knowingly holding an “innocent person criminally liable” and, as per NBC’s report citing the Russian Investigative Committee’s Telegram post, he, along with three ICC judges, allegedly issued unlawful decisions.

So, where does this case move from here?

Experts say these charges are just the beginning, and over time, more are expected to be added, including accusations of Russia’s strategy of targeting civilian infrastructure, such as power and transport.

In February, Ukraine’s Prosecutor General, Andriy Kostin, was quoted by CNBC stating that his country had documented over 65,000 Russian war crimes, which included acts such as “indiscriminate shelling of civilians, willful killing, torture, and conflict-related sexual violence”.

Furthermore, the Russians have not clarified whether President Putin will attend the August BRICS summit in person or if he will opt to participate online. Even if he comes, the chance of South Africa acting on the ICC warrant is wafer thin.

The ICC, due to a lack of enforcement capabilities, currently possesses limited authority to take any meaningful action.

Moreover, the Hague-based court does not conduct trials for individuals in absentia. Therefore, for the case against Putin to progress, he must either voluntarily surrender himself to the ICC or be apprehended by a cooperating government.

However, both scenarios look quite impossible as Russia is not a pushover and another superpower China is backing Moscow.

Besides, Putin has been known for travelling with care and these happenings will make him further cautious to take any kind of risk that may prove costly.

An analysis of Putin’s past itinerary based on information on the president’s official website shows that since the beginning of the war, he has made eight visits to foreign nations (excluding captured Ukrainian territory), just one of them Tajikistan being a member of the International Criminal Court.

The Central Asian nation was a part of the former Soviet Union and is considered as Moscow’s traditional ally. Besides, Dushanbe remains highly dependent on Russia for both money and security.

The other countries that Putin visited after the beginning of the war include Turkmenistan, Iran, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Belarus. Most of them are Russian friends while countries like Iran have no love lost for the West.

In 2023, Putin has not stepped out of his country even once. His last working trip as reported on the president’s website was on April 18, 2023, to Russian-controlled parts of Ukraine’s southern Kherson region and he attended an army command meeting. Putin is also the Supreme Commander-in-chief of the Russian Armed Forces.

Not just bilateral, the Russian president has also avoided his personal attendance at multilateral meetings outside a select few friendly nations and instead has opted to send his Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov and Deputy Prime Minister Andrey Belousov in his place. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in November 2022 in Bangkok (Thailand) was attended by Belousov while the UN General Assembly in September 2022, ASEAN in Phnom Penh (Cambodia), and G20 in Bali (Indonesia) in November 2022 were attended by Lavrov.

On Wednesday Russia had warned the Moldovan president for agreeing to comply with the ICC judgement and arrest Putin should he visit the country.

For the US and the Western powers, the sight of BRICS members standing side by side holding hands while remaining silent on the Russian invasion will not be a welcome sight. Among the four BRICS nations, only Brazil has voted to condemn the Russian invasion at the UN, that too under Western pressure.

Earlier, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva had blamed Ukraine in part for the current mess and questioned the US and Europe for fueling the war by supplying weapons to Kyiv.

No wonder, Washington in the ICC warrant at least sees an opportunity to embarrass Putin. “I think it’s justified,” US President Joe Biden has said, welcoming the ICC’s decision.

In the current scenario, however, experts believe that the warrant carries more symbolic weight, indicating that a significant part of the world (123 countries and States Parties to the Rome Statute) may become off-limits for the Russian president.

Additionally, it would require an incredibly arduous and coordinated global effort to establish the crime, making it even more challenging to prove Putin’s direct involvement.

Notably, Putin and Sudanese leader Omar al-Bashir are not the only heads of state who have faced scrutiny from the ICC in the past. Former Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo, for instance, was acquitted of all charges in 2019 following a three-year trial. Likewise, Kenya’s President William Ruto and his predecessor Uhuru Kenyatta faced charges by the ICC prior to their election.

Comments

0 comment