views

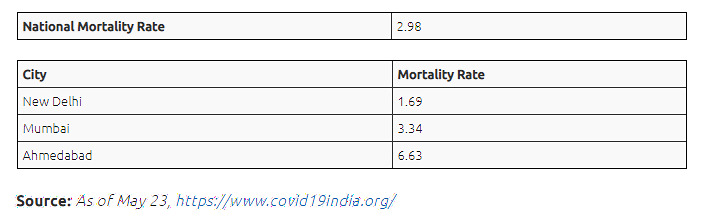

The sharp increase in Ahmedabad’s mortality rate has posed a myriad of complex questions to all stakeholders involved in this fight against COVID-19 – civil authorities, health workers and doctors alike. With a spike in the number of cases, the mortality rate has likewise increased. The civil authorities attribute these losses to late hospital admissions and underlying co-morbidity; a reasonable explanation as co-morbid patients across the globe face a higher risk of succumbing to COVID-19. Despite this explanation, Ahmedabad’s mortality rate is higher than the national Indian average, and shockingly almost twice the mortality rate of Mumbai- the worst affected city in India.

An analysis of Ahmedabad’s COVID response at all stages – preparatory, during and aftercare needs to be evaluated to find answers.

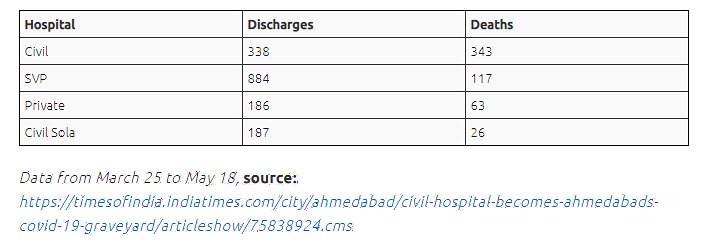

In a cruel turn of events, the Civil Hospital in Ahmedabad, a 1,200 bed designated COVID-19 hospital is now called the ‘graveyard’ of Ahmedabad. During the period from March 25 to May 18, the hospital recorded more patients’ deaths (343) than those discharged (338), a statistic which merits greater scrutiny. Anecdotal conversations with essential workers in Ahmedabad has helped bring to light contributing factors that have received little to no attention.

Failure to implement basic containment policies and the ill-preparedness of civil authorities has exacerbated the problem and weakened the state response. Prior to the designated COVID-19 hospital (Civil Hospital) becoming functional, patients were admitted to the Old Civil Hospital. In the absence of formal procedure, there was no exclusive differentiation between the COVID-19 ward and the general ward. Health workers came in contact with both sets of patients. The delay in having a nodal infection control centre and the infrastructural compromises made to hasten operation, have cost Ahmedabad.

Additionally, the civil authorities failed to involve a medical expert in their decision-making process, this obvious error is directly responsible for the late implementation and reduced efficacy of policy measures. For instance, despite the Civil Hospital being overwhelmed for some time, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) expanded the number of COVID-19 designated hospitals (now 42) only on May 16th. A timely intervention would have eased the burden on the Civil Hospital.

While free-cost of treatment should never be used as an excuse for a lower standard of care, it likely plays a role in the Civil Hospital capabilities being overburdened so swiftly.

The nurse to patients ratio of 1:4 highlights the shortage of healthcare workers. With relatives prevented from entering Covid-19 wards, the workload for nurses has doubled as ensuring food, hygiene and sanitation has to be maintained. Doctors whose prime responsibility has traditionally been medical management now have to oversee logistical functions, including food and water for patients.

Critically ill patients in the ICU face a similar disadvantageous nurse to patient ratio. The lack of trained class IV nursing staff means during an emergency; valuable time was spent training the staff mid-pandemic than addressing patient concerns. Instead, they should be trained for basics like PPE donning and doffing, oxygen monitoring, blood Pressure check, and random blood sugar checks by the medical residents.

AIIMS New Delhi safety protocol required mandating N95 masks for all health workers in the general ward as well. In the absence of any such protocol in Ahmedabad, healthcare workers have a greater risk of infection, which is understandably going to impede the delivery of care.

There have been instances in the last few weeks of doctors testing positive and being stranded with high fever, as hospital management have no protocols in place for dealing with treatment for doctors. This explains why 102 staff members working at the Gujarat Cancer Research Institute located in the Civil Hospital campus tested positive. A shortage of essential medications like Insulin, Labetalol, Noradrenaline, Adrenaline, Anti Hypertensives, Catheter, Ryle Tubes at the COVID-19 dedicated hospital has resulted in compromised patient care.

The unavailability of supporting staff like dialysis technicians, ECG and blood technicians in the Civil Hospital, has caused in delayed blood reports and sampling, further exacerbating this health crisis. The absence of a streamlined procedure for patients requiring emergency blood transfusion results in life-threatening delays.

There are instances of up to 25 people being denied treatment and were kept waiting for more than five hours at the Civil Hospital. Similarly, a Head Constable was refused entry into SVP and Civil Hospital. The reasons for refusal range from ‘lack of beds’ and ‘not ready to admit’ but most importantly reflect the degree of mismanagement in Ahmedabad. The decision to purchase 900 ventilators without any proven results, is rightly controversial and careless.

Against this backdrop of overworked medical workers, fragmented medical facilities and inefficient policymakers – patient care is deeply compromised- all these factors contribute to Ahmedabad’s high mortality rate. It is quite surprising when Dr. Randeep Guleria, Director, AIIMS visited the COVID-19 hospitals, were these factors largely discounted for. As the state government seeks to gradually ease restrictions and lift the lockdown, it needs to consider the ramifications of a second wave and subsequent spike in cases. The capacity and capability of its hospitals at present seem shaky at best.

The article first appeared in ORF.

Comments

0 comment