views

In the gloom and doom surrounding every discussion on the Indian economy, what is being ignored are the sustained efforts by farmers and the proactive policies of the government to ensure that India’s post-COVID rural economy is poised to grow at a fast pace. In recent months, the government has delivered the country’s largest-ever direct cash transfer in Indian agriculture.

This reform is the single-most important factor that will boost the rural economy. The pumping of thousands of crores directly into the pockets of farmers will significantly impact the consumption cycle—which will, in turn, create the demand to kick-start the economy. India’s rural economy constitutes more than 46 per cent of the national income; nearly 70 per cent of our population still lives in rural areas. Hence, any increase in the income of the farmers has the biggest impact on the Indian economy.

COVID-19 has impacted almost every sector, the most affected are hospitality and tourism. It is only the rural economy that has largely remained relatively immune to the impact of COVID-induced economic disruption. Due to decentralization of lockdown decisions by the Narendra Modi government, state governments have been able to control the disruption to supply chains. But demand is yet to climb back to pre-COVID levels.

The past three months saw selective lockdowns in COVID hot spots. Economic demand is not only dependent on consumers’ propensity to spend; it is also dependent on other factors like their trust or belief that the overall economy will improve. In crises, essential purchases continue but high-value discretionary purchases slow down as they are driven by sentiment. This is why it is extremely important that some of our leaders who are always painting a dark and negative future stop doing it. It is not helping their political cause; instead it is causing enormous damage to the spirit of India.

A Win-win Situation

There has been record wheat production of 109.24 million tonnes in the current Rabi season. The government gave farmers an MSP of Rs 1,975 per quintal for wheat, among other Rabi crops. More importantly, the price of mustard and masoor dal in open markets was above their MSP—by 25 per cent and 7 per cent, respectively. This rise in the realization price for these two commodities means that the farmers who sold them made a much higher profit.

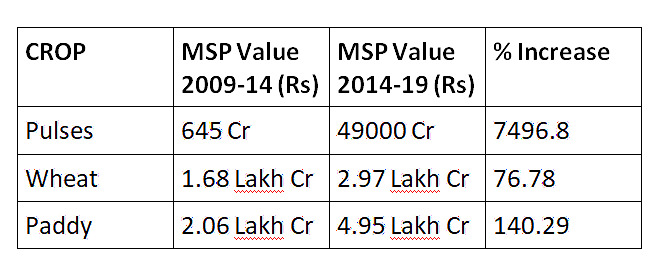

The Modi government has over the last seven years increased procurement from farmers by almost 1.5 times for wheat, and more than 77 per cent for paddy. Pulses were not even being procured by the previous governments and the country was dependent on imports, leading to irrational spike in its prices. Now, the government procurement from farmers stands at more than Rs 49,000 crore, and this money is going directly into the farmers’ wallets.

The rise in prices of masoor and mustard during the current procurement period shows the success of the private market in helping the farmer realize prices higher than MSP. This was the original vision of the minimum support price. Diversification, away from paddy, will further enable the farmer to get a higher price.

The advantage of receiving the procurement price directly cannot be underestimated. Earlier, this money would go through the commission agents and the farmer would never get the full money, and never on time.

DBT (Direct Benefit Transfer) has certainly improved the purchasing power among the rural population, with more cash in their hands; earlier, through the arthiyas (credit-linked commission agents), farmers got the least cash-in-hand after deduction of high interest-ridden debt.

Farmers of Haryana and Punjab got Rs 42,862 crore in their bank accounts under Rabi procurement. Haryana farmers got an estimated Rs 22,000 crore for the Rabi crop and Rs 2,588 crore in eight instalments under the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi, a cash support of Rs 6,000 a year, in three instalments.

Direct payment in farmers’ bank accounts through DBT is a big reform aimed at streamlining procurement processes and other benefits under farmers’ welfare. DBT shows the government has the capacity to become more responsive, inclusive, agile, and flexible on farmers’ welfare.

Breaking the Cycle of Exploitation

The intention behind direct payments to farmers is not to bypass Arhatiyas but to improve transparency in the process and provide best options to the farmers for their economic freedom. For decades now, scholars of agrarian India have studied a problematic and pervasive phenomenon known as interlinked or interlocked markets. They have been especially troubled by the interlinking of credit with commodity marketing in certain agrarian systems, where farmers are forced by the circumstances to take informal loans from a moneylender-cum-commission agent through whom they must then sell their harvested produce.

ALSO READ | The Men in the Middle: Why Government’s Direct Payment to Farmers Has Angered Arhatiyas

In repeated long-term exchanges, farmers, especially those with limited access to resources and support, become dependent on arhatiyas, giving rise to multiple opportunities for exploitation. The precise means by which farmers are squeezed in such intimate economic and social relationships are often subtle and usually opaque, although almost always acutely felt. Now that Prime Minister Narendra Modi is serious about strengthening the terms of engagement for farmers in the markets, the government must first recognise and then competently replace, or substantially reduce, the need for the multiple services that arhatiyas provide farmers.

The problem—and major source of ‘profitability’— comes from the arhatiyas’ informal money lending activities. This makes them quite distinctive from market intermediaries and aggregators in grain markets elsewhere; in Bihar, for example, we typically find no evidence of credit inter-linkage and slim margins. Moreover, in Haryana and Punjab, the credit relationship does not affect all farmers equally; it disproportionately binds those farmers who are largely excluded from formal credit channels and services, especially small and marginal farmers, tenants and sharecroppers. Fieldwork in these markets also shows that they often extend credit to numerous farmers who are unable to access and repay their Kisan Credit Card (KCC) loans on the six-monthly rotation schedule; this prevents defaults but extends indebtedness.

Now, through DBT, small and marginal farmers have sufficient liquidity to shift towards formal institutional credit channels like the KCC to avoid heavy interest-ridden debt from money lenders or arhatiyas. Now is the time for the RBI to seriously consider differentiated banking licences for the agriculture sector. There will be many takers for the rural sector, who will do a better job of providing and spreading credit for much-needed reforms, such as crop diversification.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Comments

0 comment