views

Pathways for Peace, a 2017 joint publication of the United Nations and the World Bank, opens with these remarks: "Since 2010, the number of major violent conflicts has tripled, and fighting in a growing number of lower intensity conflicts has escalated. In 2016, more countries experienced violent conflict than at any time in nearly 30 years."

Wars between nation-states have seen a sharp decline, but intra-state conflicts, a large number of which could be classified as ethnic conflicts, continue to plague the world. And some of these have been extremely deadly -- the Second Congo War, the Rwandan genocide of 1994, and the conflict following the break-up of Yugoslavia have collectively caused about four million deaths.

An ethnic group is a category that is set apart and bound together by common ties of race, language, nationality, or culture. In many ways, the concept of ethnic identity goes against the notion of a socially cohesive nation-state, and this has resulted in conflict between the state and ethnic minorities. Minorities rebel when they feel that their identity, economic well-being, and political representation is at risk from the majority community.

Of late, religion has increasingly been viewed as the primary driver of ethnic conflict. Islamic extremism has spawned vicious terror organisations that straddle across the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia and have carried out attacks in North America and Europe. The Islamic State even established a Caliphate, for about four years, over 50,000 square kilometres of territory with a population of 12 million people. Jammu and Kashmir has seen a similar phenomenon. Burhan Wani and Zakir Musa, two of the most well-known terrorists in Kashmir Valley, had called for the enforcement of Islamic rule and Shariah in Kashmir.

There is, therefore, a strong case, particularly in the West and among Muslim nations, for directly addressing the religious aspect of ethnic conflict by a strategy that is focused on countering violent extremism and religious radicalisation.

There is also a different argument. Joseph Rothschild, one of the great thinkers on ethnic conflict, said that whether mobilisation of communities happens around religion, race, or language “is irrelevant, since any and every one of them can be sacralised into a symbolic focus of ethnic mobilisation and politicisation, and this process is more or less the same whichever marker-criterion is selected.”

It has also been noted that whichever element of ethnicity is used for mobilisation, the demands of the group may not be directly related to it. Religion may be used for mobilisation, but the demands could be for political autonomy, greater economic rights, cultural freedom, etc. Therefore, focusing excessively on the religious angle of ethnic conflicts may leave the real needs inadequately addressed.

There is a vast body of research on the causes of ethnic conflicts. John Burton developed the theory of human needs as a basis of understanding social conflict and its resolution. In Burton's view, the need for recognition, security, identity, and personal development are the primary drivers of conflict. Burton also wrote that the concept of democracy leads to the assumption that “minorities should be prepared, not only to conform with the discriminatory norms of the majority, but that individuals have the inherent capability of such conformity. Secession movements are sometimes sought as an alternative to conformity. They are usually opposed by the majority on the grounds that they are disruptive of the nation-state. They are, nevertheless, pursued even at great cost by a human need for identity.”

In India, we have generally followed the human needs approach to resolving ethnic conflicts and have had very significant successes in winning over the minorities. The grant of statehood to communities of the Northeast, the establishment of autonomous councils, and the Sixth Schedule were crucial elements in ensuring that minorities could feel secure about their rights and identities.

Countering religious radicalisation is essential for western nations as their threat is primarily from lone wolf extremist individuals. These countries do not have the diversity of India and the challenges that we face in managing our minorities. We have had our share of communal problems, but our most enduring conflicts, those in the Northeast and Maoist areas, have not been about religion. Perhaps the Kashmir problem could be framed in religious terms, but it is equally about the Kashmiri, Dogra, Kashmiri Pandit, and Ladakhi identity.

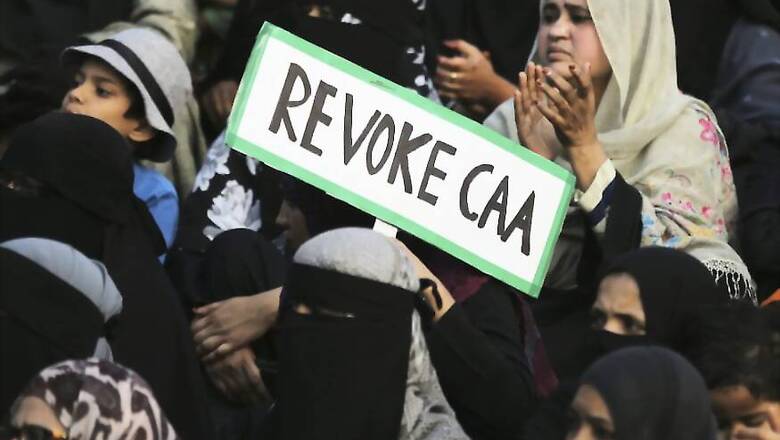

Majoritarianism is the biggest fear of ethnic minorities. The protests following the Citizenship Amendment Act have clearly brought this out. The Muslim minorities view the Act with a religious colour while the states in the Northeast see it as a threat to their ethnic identity, both from Hindu and Muslim immigrants. The reasons for the protests are different, but the apprehensions are similar.

India is the most plural society in the world and proud of its 'unity in diversity' label. However, this unity requires constant negotiation between the state and its diverse people. In this negotiation, the human need for identity must occupy the centre stage.

(The author is former Northern Commander, Indian Army, under whose leadership India carried out surgical strikes against Pakistan in 2016. Views are personal.)

Comments

0 comment