views

Four years on, the Jats and Muslims of western UP have accepted their past. But they have not drowned in their atrocious history.

To accept one's past---one's history---is not the same thing as drowning in it, wrote James Baldwin in his searing essay The Fire Next Time more than 50 years ago. For Jats and Muslims of western UP, drowning in their recent dreadful history was not an option they could accept. Four years ago, as a communal tornado tore through their rich lands, both the Jats and Muslims were laid low by the vicious storm. They, who had existed together peacefully for years, were tense; their lives were fraught. Anything could happen. Peace could just become a football to be kicked around by two intensely rival sides. And for a time it was, horribly. And then it suddenly stopped.

Four years on, they have accepted their past; accepted that it has become sullied. But they have not drowned in their atrocious history.

In Baghpat, sitting in a pokey office whose door is kept open to the various sounds of the crowded bazaar, a paunchy Mufti says Jats and Muslims have forgotten their sins, their past errors and made peace again. But what about polarisation? What about the communal rupture? Baloney, says the Mufti, his face craggy as if worries of the past four years had made a permanent home on it. Mufti Wajahat Qasim, dressed in Muslim preacher white and almost talking saffron logic? Towards the end of the long conversation, the Mufti who was first cagey about his political affiliations, says he is aligned with the BJP for many years, and claims to have worked closely with Rajnath Singh and Indresh Kumar.

His bloviating discourse on communal amity is something that surprisingly has many takers in these badlands, even among the proud, hookah-smoking Jats. But his political logic, his open, almost sentimental admiration for the saffron party, is not borne out by Muslims in these areas. And not many Jats, too, agree with him.

A relaxed group of old Jats, taking slow turns on a water pipe, sitting outside a palatial house that even boasts a gym on the road to Shamli from Baghpat, are almost vehement in its support for Ajit Singh's Rashtriya Lok Dal. Yashpal, Sukhpal, Rampal...their names evoke Jat machismo and their geriatric bodies still have enough heft and muscle to put a middle-aged city man to shame. And they puff at their pipe, in a collegial gesture of amazing camaraderie, with vigour. We know, Sukhpal says and the others nod their wizened heads in agreement, RLD is not a big player; we also know we should vote BJP; but we are Jats and we will be punching the button for Ajit. After all, he is one of us. He is a Jat and Chaudhary sahab's son. A strange logic but one that reminds of that famous Sunny Deol dialogue: ‘No ifs and buts, only Jats’. Any trouble with Muslims? None, they say. Everyone has accepted it and moved on. Muslims and Jats have existed in harmony for centuries here and they will continue to in the coming years too. They have accepted the past and have refused to be drowned in it.

Some distance ahead, Faizad Khan, the owner of glitzy Fauji Dhaba, agrees. As his minions rustle up dhaba food and serve his customers, Faizad also says Jats and Muslims have to live together. They are conjoined. He disagrees with the Mufti and says Muslims are not all gravitating towards the BJP. This is bull, he says, passing instructions to his cook to spice up the dal. He gets a decent pension as an army retiree, but does not think the Modi sarkar will benefit from OROP (one-rank-one-pension scheme). His vote is for Akhilesh, whom everyone agrees has done a fair amount of work. His minions are busy dishing out food, but even Faizad is unsure about the recipe for political success in these areas. The Jat vote will split, the Muslim vote for split, the dalits will adhere to Mayawati...who will win then? Scolding a waiter for a badly done roti, he says he does not know who will knead the political dough.

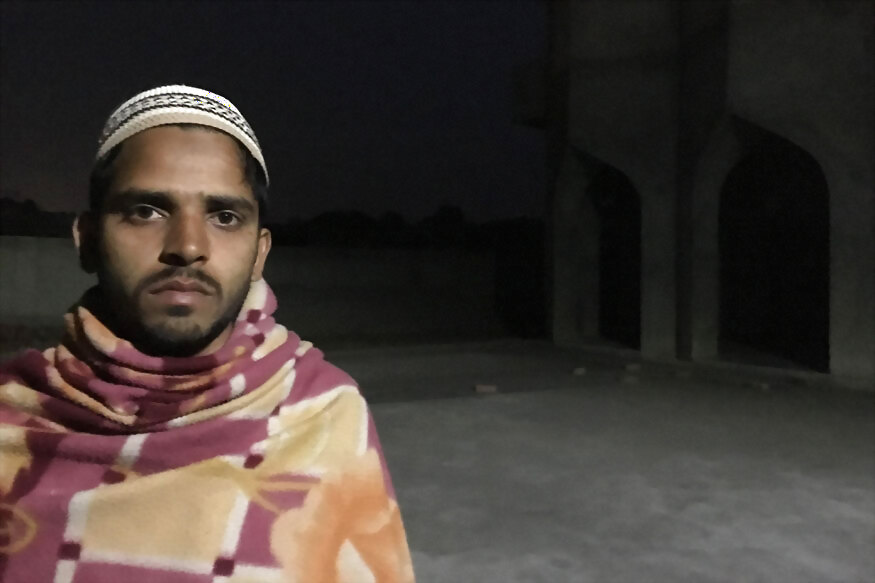

Many though have come and kneaded their political dough at the rehab camp in Kairana. Four years ago, when this region erupted in violent, murderous riots, a camp for 307 families was set up on a 22-bigha parcel of land loaned by a politician, who unfortunately died in a car accident. The camp consists of tiny ramshackle, dinghy houses on plots of 50 square yards and is deliberately kept poor. Even the mosque, for huge money and support have come from Deoband, gets patchy electricity. It remains a raw cement structure, still perhaps waiting for funds for a coat of paint.

Inside, in poor emergency light, a bunch of kids reads from the Koran. They lift and bow their heads in unison, droning on machine-like about whatever they are reading. They are not imbibing; they are just droning. It's education by rote. The preacher, who sits crosslegged, keeps scolding kids who, while reading, fall asleep. The Arabic script is barely visible in that light, but the preacher says it is mandatory for the camp kids to come to the mosque and study Koran. English? Well, he says, a school is being set up. The mats on which the kids sit are going damp and cold in the evening winter.

Outside, the political temperature may be soaring; but inside the beat-up, grimy structure that is the mosque the studying kids battle the slowly enveloping cold in their tattered sweaters and hole-riddled shawls. As the kids continue to drone, the men outside narrate horror stories of four years ago. The tension has lessened, they say; but they still are not comfortable going back to their homes. Some of them don't even want to go; some want to stay on bizarre reasons. Their families have rejected them and so they are staying on. Like in all camps, the narratives stay personal but vary dramatically when it comes to impersonal. But they all stay alive to politics.

Politics is a strange beast. Sometimes it exterminates; sometimes it binds. But politics---good, bad, ugly---also helps you to deal with your dreadful past and accept your history. For those who don't accept their histories, drowning is the only option that remains.

Comments

0 comment