views

Preparing in Advance

Meet with the director and producer. Though each production is different, odds are at least one of these two will become your new best friend. They definitely have expectations for the production and for you, so start off on the right foot by asking what those are! Are there any duties they want to do themselves? Some directors like to take things into their own hands. How do they want rehearsals run? Do they have any specific guidelines you should be aware of? And be sure to establish a routine where you two or three can check-in with each other post-rehearsal.

Be an organizational machine. Months before rehearsals begin, you'll need to start scheduling and coordinating. A good stage manager can take in all of the scheduling needs from the director, music director, vocal director, choreographer, fight choreographer, dialect coach, movement coach, production manager, costume designer, etc. and reasonably accommodate everyone's needs in a timely manner. Basically the stage manager is a miracle worker. You'll need to come up with the following: Contact sheet Rehearsal schedule Email lists Conflict calendar Production calendar Daily Reports Properties List (keep updated) Set Design communicated to all staff (keep updated) Furniture and Set Decoration list (keep updated) Costume plot (keep updated) Set dates for production meetings. And this is just the paperwork prior to the run...

Meet with the technical director. He or she is probably the one that'll give you a set of keys. How else will you be able to do your job? Talk with them about what they see as the biggest obstacles in the show and what you should know about the set up of that specific theatre. Take a thorough walk around the theatre, familiarizing yourself with everything from emergency exits to the most convenient trash can. This theatre will be home for the next few months -- the quicker you get to know it, the easier your job will be.

Prepare your Stage Manager kit. Since you're basically Anne Sullivan and the show is Helen Keller, you need to be prepared for anything. When anything goes wrong, even the director won't be the one everyone turns to: it'll be you. So stock your kit with everything you could possibly need. But here are a few ideas to get your started: Band-aids Batteries Chalk Erasers Paper clips Pens Ruler Safety pins Scissors Small sewing kit Stopwatch Tampons

Prepare your prompt book. This starts off with the script blown up in a binder. Make it one-sided, hole punched on the right. That way on the left of the binder you have the script, and to the right of it you can place a blocking sheet (hole punched on the left). If you have a ground plan of your set, add that in too. You don't have to do it just like this, but you should have something similar. Having a book that has everything you need will keep you sane. Include post-it notes or other markers to make everything easily accessible. Blocking sheet templates can be found online. You should have a template for everything, really.

Know the script like the back of your hand. This show is your baby. You need to know when a "the" gets dropped, when a prop enters a line too late, when the spot is 6 inches (15.2 cm) to the right, etc. Knowing it so well you can see it when you close your eyes sounds stressful, but it makes everything so much easier. Knowing the script will help you: Generate a scene breakdown Make a prop plot Know all costume needs Be sure to have this done before or during "prep week" -- the week before rehearsals start.

Form your crew. Line up the crew that will be working the show and clearly communicate what you know of the show needs to them. Everything is still in its preliminary stages, but the sooner you know you have other people you can depend on, the quicker you can relax. Your ASM (assistant stage manager) will be your right hand. When you can't be in two places at once, they'll be getting the job done. You'll also need crew for lights, sound, props, and working backstage. The size of your production will determine how many people you need.

Running Rehearsals

Track everything. After a rehearsal, you basically need to be Rainman. What was that blocking note that the director gave around 7:45? Boom, you have it written down, no worries. You'll be taking notes on blocking, choreography, length of scenes, notes for rehearsal report, lighting and sound cues, etc. It seems like overkill until the one time when the entire show hinges on something you have written down on page 47 of your book. It's imperative that you have a good system of shorthand down pat. And it should be legible if, God forbid, you ever get sick. So besides the standard USL, DSR system, get something consistent down for blocking and choreography patterns and all cues. That way you won't be scrambling 32 counts behind.

Be the timekeeper. Every show has that person who's notorious for being late. It's your job to call them up and make sure they're not dead and if they're not dead to chew them out for being late (in a civil way, of course). When everyone and everything's ready, you get the show on the road. When the city wants you out of the building, you're keeping an eye on the clock, too. Otherwise these things will go on for hours. You're calling breaks, too, and making sure one person with authority doesn't hog all the rehearsal time. Basically you keep things ticking. You're the time and the timekeeper.

Know that you may be on book. For some theatres (and provided you're not working a dance show), you'll be the one on book. That means when an actor drops a line, you call it out. You need to constantly be focusing and following along. If an actor doesn't know a line and you're not there to pick up the slack, you're losing seconds constantly and you will end up being behind schedule. "On book" means you have the script in front of you. Everyone else may be "off book," but you're the one ready with the script because just because everyone is off book doesn't mean they should be. And for the record, actors drop lines all the time.

Pull props or rehearsal props. With your props master or mistress, you'll need to coordinate something for rehearsals. They may or may not be the real props, but you'll need something akin to what the actors will actually be working with when the show opens. Requests will naturally crop up as rehearsals progress and you'll need to provide something shortly thereafter. But you know the book so well, you saw that coming, right?

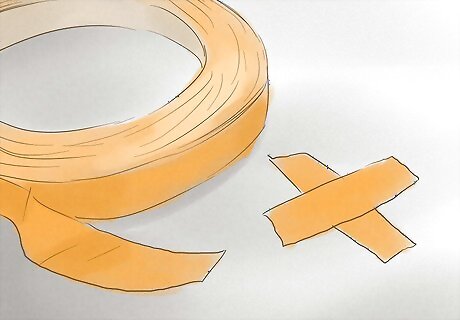

Spike the stage. If you're lucky enough to be working in the theatre the show is going up in and you're lucky enough to have a design and the actual props to work with, you'll need to have the stage spiked. That means putting that cool glow tape on the stage where the set pieces go. What colors do you want to use? Make sure to spike the upstage side of every piece. You don't want tape chillin' in front of every piece you have onstage. The audience might notice that.

Let the team know when something isn't possible or correct. There will probably come a time when your director wants Sheila to exit stage right, make a quick change, and enter stage left fifteen seconds later. There will be other times when your director tries to design a hazard symbol from memory and, unbeknownst to her, it turns out more like a flower. It's your job to kill her fierce display of obliviousness -- you have to chime in for the good of the show. If something isn't possible or correct, speak up. However, it's not your place to offer artistic vision. The only time your opinions should come into play is when the director (or someone similar) asks. You're logistics here, letting them what will work and what won't -- not what vision you think the director should have.

Delegate. Obviously, your hands are going to be quite full, and that's one heck of an understatement. Because of this, you need to delegate. That's what your crew is for! Think of the ASM as assistant to the stage manager. Call the shots. Don't be worried about coming off as bossy -- the show needs to go on and you can't do it all yourself. An easy job to delegate is to make sure the rehearsal space is safe. Sweep (and mop, if necessary) the stage before rehearsal and make sure all is kosher afterward, too. Especially if you're renting the space. Reset the stage between each scene. Each night there will probably be several scenes that are being rehearsed; it'll be quickest if you or someone on your crew resets the stage instead of watching the actors fumble with things they shouldn't be fumbling with. Be hands on and ready to pitch in on everything. There is no such thing as "not my job" or a job that's beneath you. This shows that you are not afraid to do a little grunt work and might ensure your job.

Send out the rehearsal report. After each rehearsal, you'll need to send out a rehearsal report to all the necessary authorities (producer, directors, etc.). Do you have a template for that? Is it in your prompt book? Talk about any issues, things that will be solved and changed tomorrow, timing, things that got done, notes for each department, and so and so forth. And then email it away with your handy dandy email list you made six months ago. If there are injuries or one of your actors end up in the ER, you have to hold replacement rehearsals to put in a replacement. This will mess up your schedule, but you'll make do.

Keep the production meetings running. It's not enough that you've scheduled them, you gotta keep them on agenda, too. That means discussing budget, safety, publicity, allotting time for each department to chime in, and making sure the calendar is out for the next meeting. And you should probably take a few notes on this too (depending on how well everyone gets along, you know). Sometimes certain departments will be absent. You are the eyes and ears of the rehearsal hall and your job is communicating clearly and effectively to all of the production departments what is happening in the rehearsal hall and what the director wants. You never want anything to be a surprise come tech week. All departments should know what is happening and what affects them. There will be a company meeting at the beginning of tech week that you'll be running. That's when you field any last minute questions or concerns, talk about ticketing, emergencies, etc. Run over the procedures and policies of the theatre and let each department add final notes if they'd like.

Do even more paperwork. You might find this as some kind of joke. Now you've gotta make your run sheet for your crew, the tech schedule, blocking script, prompt script, and a calling script (production script). But the good news? That's it for paperwork! Well, apart from the stuff you fill out every day. Your run sheet is a sheet describing what the crew has to do. Keep it as simple as possible yet still discernible by anyone who walks onto the job never having seen the show before. Basically, you write the cues, what pieces move and where. That's it. You're calling the cues for sound, light, fly, motor, and stage, so you'll need a calling script for yourself.

Running Shows

Make sure everything and everyone's safe and ready. Are all the actors and crew present? If not, call 'em. If so, great. Now you have to make sure the deck is swept and mopped, everything is preset for the top of the show and it's all ready to go. If there are any hitches, people will probably come to you. It'll change every night.

Call times. You're still the clock, even though you're out of rehearsals. Keep everyone posted on the countdown. Let them know at a half hour before that the house is open. Let them know it's 20 to places. 10 to places. 5 to places. And, finally, places. And make sure they say, "Thank you, 10!" (for example) before you assume they've heard you. You'll also probably be letting everyone know when the stage is open and closed (for things like flying and whatnot), when physical and vocal warm ups are, etc. Basically when anything happens, you alert the masses.

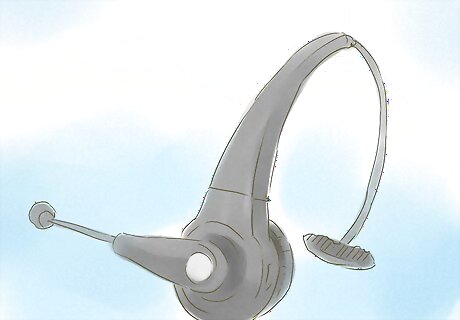

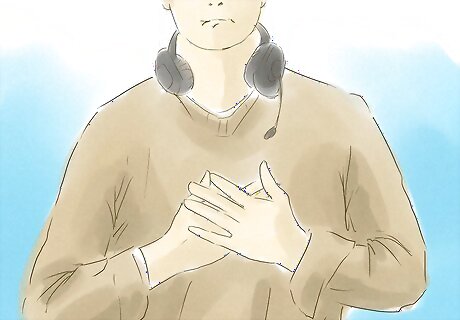

Go through headset protocol. If you have a crew of veterans, this won't be that big of a deal. But the odds of everyone being seasoned aren't great! Assume they could all use a brush up and go over headset protocol. Here are a few things: You will say "warning" and the cue number and whom it affects ("warning on deck cue 16," for example). The affected person should then say "Thank you, warning." After a warning, you will say "standby," as in "standby deck cue 16." The affected person should then say, "stage left," or "lights" or whatever their department is. When a standby is called, there is no more talking. When it is time for the cue, you call "GO." There is no response to this. You are the only one allowed to call the final go. Headset banter is a natural part of working backstage. It's a great part. Just know when it's appropriate and when it's not.

Work with the house manager. Every night you'll have a front of house info sheet to fill out about ticket sales and box office issues. Your house manager and you will work out a system. But for their sake, keep your routine habitual. Try to show up at the same time and place each night so they can predict how things work with you. Co-ordinate with the front of house manager of when to open the house (generally half an hour before) and when to start the show. Do you hold the show by 5 minutes because the line at the box office is huge? Patrons can't find parking? Is it raining? They'll let you know if anything out of the ordinary is happening out front -- it's just as important as what's happening in the back!

Call the show. That headset protocol we talked about? That's the stuff you'll be using to call the show. So at 5 to places, you'll head up to the booth (or wherever you're calling the show from), and your team will assemble. You've talked to the front of house, the headsets are on, the audience is ready, and you're ready to call cue 1. Curtains open!

Type up a show report. This is used to tell the production team how it went, the length of the show, the house count, and any problems or anything that needs to be fixed before the next show. With any luck this'll be totally repetitive every night and you'll be able to do it with one eye closed and an arm tied behind your back.

Having the Qualities of an Effective SM

Work with experienced SMs. You may think years of being a techie is adequate preparation or taking a few classes in high school or college, but it's no substitute for working with a good SM or two. As you can see, SMs have to have people skills, technical skills, foresee problems, and be organized as hell. This position obviously takes a very precise type of person! While, yes, a good SM can locate a screwdriver in seconds and get to working on a breaking set piece, they can also coordinate with directors and actors -- two very different types of people -- and predict their problems. A good SM has multiple types of intelligence, quite obviously.

Be a likable leader. Fine line, huh? You must be likeable but also be able to maintain your authority so that the cast and crew listens to you and respects you. If you aren't likeable no one will ever want to work with you again; if you aren't respected as an authority you cannot ensure the safety of the cast and crew. As you can see, you are an integral cog in the machine of the show. If you don't lead, chaos will ensue. Establish control from the very first audition. Though a stage manager should not be feared, they should be respected. No need to scare people into listening to you, but don't be afraid to be firm when you need to be. Expect respect from the beginning of the process and respect the ones around you as well.

Have the director's best interests at heart. It's important that you have the keen ability to maintain the artistic and technical integrity of the show. It is your job as an SM to maintain the director's vision during the performances of the show, whether there are 5 performances or 500. If things change, you need to rein 'em back in. Even if you disagree, it's still your job. Does the director want the scene lit so dim that you can barely see the actors? Well...okay. Sure. That's how it's going to work for the rest of the run -- even when the director doesn't show up.

Stay calm. If you don't do anything else on this page, take this one little grain of wisdom seriously: It's absolutely imperative that you stay calm. If you lose your cool, everyone else will too. The show will go on, it will be okay, no one will die (probably). So set a good example and stay calm. You have an entire crew that will tackle the problem. Let's say it one more time for good measure: stay calm. Yeah, you have a billion things on your plate. You do. You won't get the admiration and praise you deserve. You won't get people marveling at your skills. But when something goes wrong, they'll still look to you. Take a breath, take a step back, and deal. You got this. At rehearsals, always set the tone for a calm and professional atmosphere. Play quiet music, keep loud talk to a minimum and, if possible, work to give the director a few moments alone to gather his thoughts when he walks into the theater. If you begin with a calm atmosphere, you won't have to ask for quiet.

Know your crew well enough to anticipate problems. There's going to be a day when your 100-pound little sister is the only one running stage right. It doesn't take a genius to know that when cue 10 rolls around, she's gonna need help rolling on the Trojan horse. It's things like that (and sometimes much less obvious things) that will crop up that you need to provide a solution for. And, not to mention, people not getting along and certain people being undependable. Who's good with a saw and who's better at untangling pom poms? Who can't pay attention for five minutes straight and who would you trust with your car? Things like that. In the event of an emergency or fire alarm you are responsible for the cast and crew and their safety. Review the theatre's policies when it comes to feasible emergency situations.

Be a drill sergeant and a cheerleader. That firm but likeable thing? That deserves reiteration, too. You need to keep everyone on task and on time and let them know when they're not pulling their weight, but you also need to cheer on the show and be a voice of positivity. Everyone else is stressing out, too. It's hell week that's going to need the most positivity from you. You have directors wondering if their show is going to come together and actors that are wondering if they're going to make fools out of themselves or not. Know that and cheer them on. So walk into the theatre with a smile and have a good attitude, regardless of what you actually think!

Apologize when you make a mistake and keep going. Since you are doing a billion trillion things at once, you will make a mistake. You will make several mistakes. Hopefully not the same mistake twice, but multiple mistakes nonetheless. Apologize and move on. Don't sulk or throw a fit. Everyone makes mistakes. It's a tough gig. You'll learn from it. And now it's in the past. Everyone in the theatre generally has a preconception of how things should work. They all think something a little different. Since there's no use in accommodating them all, do what feels right to you. Take their suggestions if they're better and ignore them if they're not. But to find what feels right to you, you'll need to mess up. That's good! Just remember to pick right back up where you left off. The show depends on it!

Comments

0 comment