views

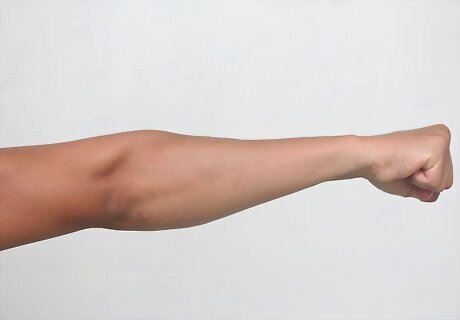

Making a Fist

Extend all four fingers. Hold your hand out straight and naturally extend all four fingers. Firmly press all four fingers together, leaving the thumb loose. Your hand should stick straight out as though you are extending it for a handshake. Squeeze your fingers together with just enough pressure to turn them into a solid mass. They should not hurt or feel stiff, but there should be no spaces or gaps between them.

Curl your fingers. Bend your fingers into your palm, curling them under until the tip of each finger touches its corresponding base. You are bending your fingers at the second joint during this step. Your nails should be clearly visible, and your thumb should remain loose at the side of your hand.

Curl your bent fingers inward. Continue curling your fingers in the same direction so that the bottom knuckles are brought out and the finger joints are tucked in. During this step, you will actually bend the third and outermost knuckles of your fingers. Your nails should partially disappear into your palm. Your thumb should still hang loose during this step.

Fold the thumb down. Bend the thumb down so that it falls across the top halves of the index and middle fingers. The exact placement of the thumb isn't too crucial, but it must be tucked under and should never hang loose. If you press the tip of the thumb to the fold of the second knuckle of your index finger, you may actually minimize the risk of damaging the bones in your thumb. Tucking the thumb under the index and middle finger works well and is a more common tactic, but you must make sure that it remains relaxed as you strike. A tense thumb will pull the bones at the base of your hand down and apart, which may increase your risk of developing a wrist injury.

Testing the Fist

Press into the gap. Using the thumb of your free hand, press into the gap created by the inner bend of the second knuckles. This test can help you determine how tight your fist currently is. Make sure that you use the thumb and not the thumbnail. You should be unable to press into the gap with your thumb, but the effort should not cause any pain. If you can break into the fist gap with your thumb, the fist is too loose. If pressing the fist causes considerable pain, the fist is too tight.

Slowly squeeze the fist. A second test you can use to gauge the tightness of your fist requires you to gradually squeeze your fist tighter and tighter. Use this test to give yourself an idea of how a properly formed fist should feel. Make a fist and place your thumb against the knuckles of your index and middle fingers. Squeeze your fist a little. The first two knuckles should tighten against each other, but the fist should still feel somewhat loose. This is the tightest your fist should feel as you strike with it. Continue squeezing your fist until the thumb reaches the knuckle of your ring finger. You should feel the first knuckle of your index finger weaken, and your little finger will squeeze inward in a manner that causes the knuckle to collapse inward. At this point, the structure of your fist is too distorted to be effective or safe to use while striking.

Using the Fist

Turn your wrist. Turn your wrist so that your palm and folded thumb face the ground. The outer third knuckles of your fist should face up. If you made your fist with your hand in a handshake position, you will need to turn your fist roughly 90 degrees when preparing to strike with it. Make sure that the structure and tension of your fist remain consistent as you rotate it.

Extend your fist out at a right angle. Your wrist should remain straight as you strike with it, so much so that the front and top of your fist should roughly form a right angle. Your wrist needs to remain firm and steady as you strike with your fist. If your wrist snaps back or twists at an angle, you may damage the bones and muscles there. Continuing to strike after your wrist has been damaged may result in permanent wrist injuries or injuries to your hand.

Squeeze the fist as you strike. Squeeze the knuckles together just before and during the moment of impact. Squeeze all of the bones withing the hand together at the same time. By squeezing your fist together, the bones can reinforce one another and work as a solid yet flexible mass. If your bones strike your target as a group of small, individual bones, they will be more brittle and prone to injury. Avoid over-squeezing your hand, however. Doing so can cause the bones of your hand to buckle and collapse upon impact. If the shape of your fist becomes distorted when you squeeze your knuckles together, you may be squeezing too tightly. Note that you should squeeze as close to the moment of impact as possible. Squeezing your fist too soon can slow you down and may make the punch less effective.

Rely on your strong knuckles. Ideally, you should make contact with your target using the two strongest knuckles: those of your index and middle fingers. In particular, it is the outer third knuckles of your index and middle fingers that you should focus on using. The knuckles of your ring and pinky fingers are weaker, so you should avoid striking with them whenever possible. Doing otherwise may result in injuries and an ineffective striking technique. If your fist is correctly formed and you are holding your wrist in the correct manner, it should be relatively easy to make contact with your target using only the two strongest knuckles.

Relax slightly in between strikes. In between each strike, you can relax your fist enough to rest the muscles in your hand, but you should not allow the little finger to come loose at any point in the process. Do not continue to squeeze the fist after the moment of impact, especially during an actual combat situation. Squeezing your fist after the moment of impact can make your swings slower and may leave you open for counterattacks. Relaxing your fist can preserve the muscles in your hand and improve your endurance.

Comments

0 comment