views

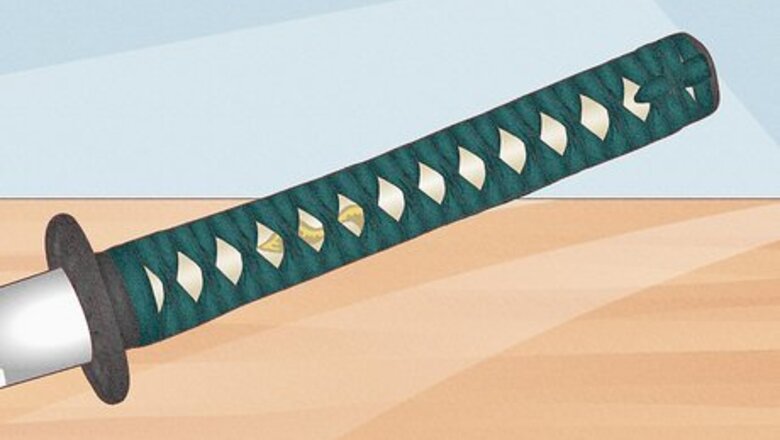

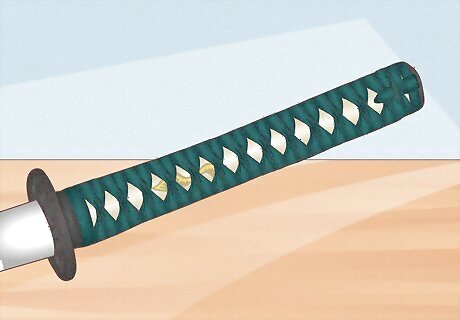

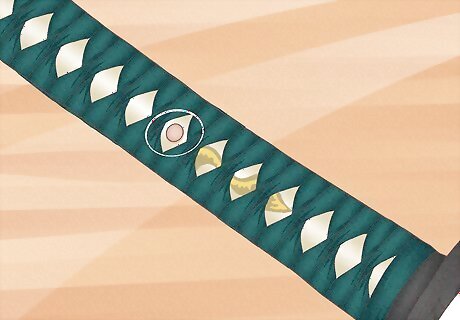

Check to see if the Tsukaito (binding) is tight. Skip this step if there is no Tsukaito.

Make sure the sword has a Sageo if you plan to use the sword.

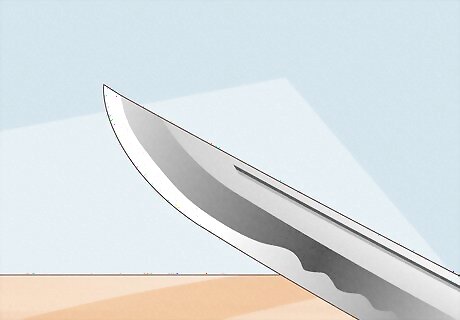

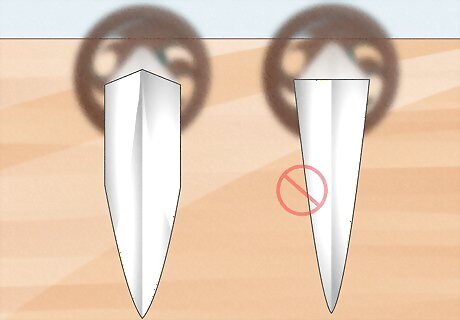

Check that the tip of the blade is not at a very acute angle.

Consider what the blade is made of. If someone says the sword is carbon steel they probably don't know what they're saying, in this context (Steel always has carbon in it otherwise it would be iron). However, more generally, the term carbon steel is useful to distinguish non-stainless from stainless blades. A genuine ancient or functional Japanese blade would not be stainless, however. If it is stainless, it is almost certainly a modern reproduction designed to only be placed on a wall - it will have little value and will not hold an edge well, if at all.

Learn how to check blade sharpness safely. If the blade has been properly maintained or is recently created for use (some genuine modern blades do exist) then ensure the blade is sharper than any kitchen knife you've ever known. Be careful of cutting yourself!

Check that the sword has a Mekuki (a peg that holds the blade to the handle).

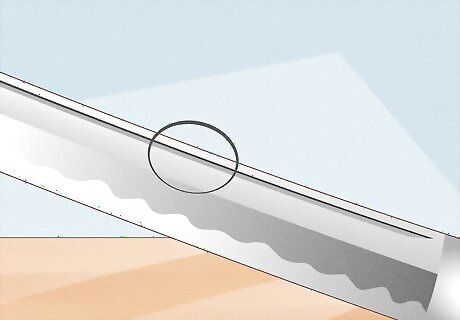

Make sure the blade is not a triangle.

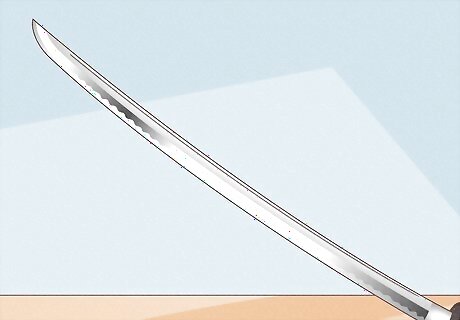

Look for the line you see going through the back of the sword. This is called a fuller in Western blade parlance, and it is generally accepted that it is used to lighten the blade, and make it more flexible, while not weakening it. Some other schools of thought suggest it exists so you could pull the sword out someones muscle and tissue which normally creates suction holding the blade in someones body (in which case it is referred to as a 'Blood Groove'). Rarely it may have been be used to cut out an impurity in the metal.

Check for shine and matte. The back of the blade and the adjacent sides should be shiny (there are katas which you use your katana to make sure no one is behind you by using the mirror-like surface of the sword), but the center and edge may be more matte (but still reasonably polished) and should have a wood-like 'grain' or water-like pattern (think ripples or waves). These patterns are unique to each blade (if genuine and not etched) and are a major part of a particular blade's beauty and personality. In ancient blades the pattern forms as a result of the layering and forging process, but in modern blades it may be 'fake' and a result of acid etching.

Understand the age of the blade since Japanese blades can be classed by the 'era' in which they were crafted (eg. Gendo for blades made from 1877-1945). As a rule of thumb the older it is the better quality it is likely to be, although the work of individual smiths is a major factor in this (ie. an ancient blade by a minor smith may not be the equal of a more recent blade by a famous master). In particular any blade made just prior to or since about WW2 has a higher probability being mass produced and/or inferior, though some reputable modern smiths do exist. On average these more recent blades would be worthwhile for training or souvenir purposes, but less so as a collectible.

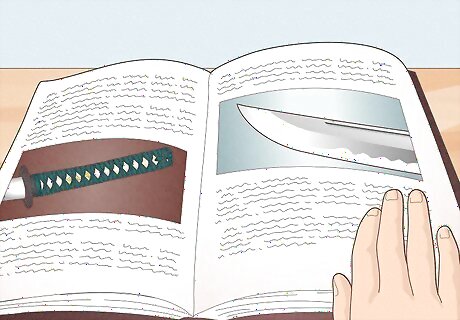

Do some research. If investing serious money then before you do so, get a good book on valuing antique Japanese blades, look at as many as you can to get a sense of them (go to a museum), or (best of all) have the item assessed by a professional. If the sword is of significant historical importance or value, and you have mucked it up by touching it bare-handed, understand that it costs up to $1,000 an inch to have it properly polished.

Comments

0 comment