views

Understanding the Facts and Legal Issues

Read the case file. The case file should contain information about the facts that you or your firm has compiled through conversations or meetings with your client. It is important that you understand these facts as they are critical to your correctly identifying the legal issues in the case. Be sure to read the entire file very carefully – missing even the slightest detail could mean you reach an incorrect conclusion. Do not dismiss anything in the file out of hand. If you can’t decipher a piece of handwriting (a doctor’s report, for example) seek help until you can be sure you’ve read and understood everything.

Review the court record. The court record consists of the pleadings filed with the court including the original complaint, any answer to that complaint, cross-complaints, counterclaims, and any number of other types of pleadings or motions submitted to the court. Depending on the stage of proceedings of your case, there may not be a court record yet. If there is a court record, read it carefully to understand the facts, procedural history, legal issues and your opponent's position.

Make a concise fact list. As you review the file and court record, prepare a list of the facts. Include only facts relevant to the legal issues. For example, if you are writing a brief on a “Motion to Compel Discovery,” it would not be relevant to include information about the opposing party’s personal life unless it had something to do with why he or she did not turn over the documents. Organize the facts into columns of “pro” and “con” (either for or against your position). Place a star next to those facts that are especially good or especially bad for your case. For each fact on your list, take note of the source in which you found it so that you have the citation on hand if you use it in your brief. For example, if you get a particular fact from the “record” on page 5, you should place (R. 5) after you state that particular fact

Make a list of legal issues to research. Based on your review of the case file and court record, identify the legal issues that are relevant to the brief. For example, in the course of defending a lawsuit, an issue might arise during discovery, with the other party refusing to turn over important documents. In that case, the issue would be whether or not the other party is required to turn over those particular documents. For each legal issue, consider what questions, if any, you would like to answer in the course of your research.

Researching the Legal Issues

Get an overview of the law. To research the legal issues in your case, you will need to identify the relevant cases and statutes. A starting point for gathering this information is to refer to sources that provide an overview of different areas of the law. Ask attorneys in your firm or other attorneys you trust whether they have worked on any cases with the same legal issues you will be addressing in your brief. If so, ask to review briefs or memos they have prepared on those issues. Consult recent practice manuals published by state Bar associations. These can be found in law libraries and online through legal research subscription services, such as Westlaw or LexisNexis. As you review these materials, take note of citations of statutes and cases relevant to the issues in your case. These will provide you with a starting point for conducting your research.

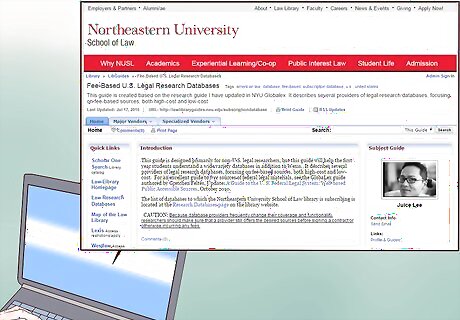

Look up relevant statutes. Once you have identified the statutes applicable to the issues in your case, look them up and read them. Search for statutes online through subscription based websites, like LexisNexis, Westlaw, Loislaw, FastCase, Casemaker and Bloomberg Law. The U.S. code and many state statutes can also be accessed for free by searching for them online. If you cannot locate the text of a statute online, go to a law library and look for it in the relevant code. "Annotated statutes" are particularly helpful, as they provide an explanation of the law and a listing of relevant cases.

Research case law. Find and read relevant cases you identified through your review of briefs, memos, practice manuals and annotated statutes. Locate cases online through subscription based websites, like LexisNexis, Westlaw, Loislaw, FastCase, Casemaker and Bloomberg Law. If you do not have a subscription to these services, look for your cases on Google Scholar, which contains an extensive database of state and federal cases that can be accessed online free of charge. Pay special attention to cases with similar facts in which the holding supports your position. Consider how to distinguish the facts in your case from cases with holdings that are unhelpful to your position.

Shepardize your cases. Before you cite any cases in favor of your position, you must "Shepardize" them to confirm they are still good law. Shepardize online by looking up the citation for your case on Shepard's by LexisNexis, KeyCite by WestLaw or similar services on Loislaw, FastCase, Casemaker or Bloomberg Law. Shepardize in print by reviewing Shepard's Citations print guides in a law library. Keep in mind that any cases that have been overruled are not binding on the current court and should not be used in a brief.

Writing Your Brief

Tailor your approach to the type of brief you are writing. There are two general categories of court briefs: trial briefs and appellate briefs. A trial brief is usually submitted during or before trial in support of or in opposition to a motion filed with the court. An appellate brief is submitted to a court of appeals in support or in opposition to an argument that a lower court's decision must be overturned. Appellate briefs are longer and more formal than trial briefs. They require a title page, table of contents and authorities, in addition to statement of facts, questions presented and legal argument. The exact requirements of an appellate brief will depend on the procedural requirements of the appeals court to which the brief is being submitted. Unlike appellate briefs which generally conform to a set format, trial briefs vary widely depending on the kind of motion the brief is intended to support and the type of court to which it is being submitted (civil, criminal or immigration court). For example, a brief in support of a motion for severance of defendants in a criminal case may look different from a brief in support of a motion for summary judgment in a civil case. If you are preparing a trial brief, ask a lawyer you trust for a template of a brief supporting the same kind of motion to the same court. Be sure the lawyer specializes in the area of law covered by the brief. Use this template a starting point for drafting your brief, while always checking the formatting requirements of your court to ensure you are complying with court rules.

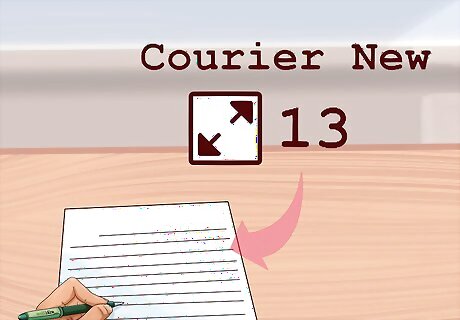

Refer to the procedural requirements of your particular court. Every brief will be formatted differently depending on the type of brief and the court to which it will be submitted. Read the court manual for your particular court for the rules that apply to your brief, including those regarding: page limits, font size and type, paper color, parts that must be included in your brief. Find out what legal citation format is required by the court. For example, although most courts require briefs to use the “Bluebook” legal citation format, in California courts, you must use the “California Style Manual” instead. Additionally, in Alabama, all briefs must be submitted using the font “Courier New” in size 13 while other courts will require different fonts. Scrupulously follow all rules. Briefs that do not comply exactly with the rules may not be accepted by the court, and may be returned unread.

Create a title page. The title page contains information identifying the case and naming the person who filed the brief. The exact contents of a title page are set out by the rules of the court. Generally, it includes: the court name, jurisdiction, case number, title of the case (the names of the parties), title of the document, name(s) and address(s) of the lawyers filing the document, and the date filed. A short trial brief may not require a title page. However, refer to the rules of your particular court before leaving it out.

Prepare a table of contents. The "Table of Contents" must contain every heading in the brief as well as a page reference for each. A short trial brief may not require a table of contents. However, refer to the rules of your particular court before leaving it out.

Compile your table of authorities. The "Table of Authorities," also referred to as the "Table of Cases," usually appears after the table of contents. It lists each case or other authority cited in the brief. Group the authorities by cases, statutes, rules, and other authorities. Within each group, list the authorities in alphabetical order. Each authority must include the full citation and a cross reference to each page in the brief where the authority is cited. If you are preparing a trial brief, you may not need a table of authorities. Refer to the rules of your particular court before leaving it out.

State the basis for jurisdiction. Write a jurisdictional statement that tells the court what authority confers jurisdiction on the court to hear the case. Refer to the statute or source of law that grants the court the power to hear the case. For example: "The court has jurisdiction under 42 U.S.C. § 1983." While a jurisdictional statement is expected for appellate briefs, it is not usually included in trial briefs. Consider the rules of your particular court and legal issues in your case to determine whether or not you should include one.

Set forth the facts and procedural history. Write out the facts and procedural history relevant to your case in a section called "Statement of the Case." In presenting the facts, be clear, concise and persuasive without including language that implies a legal conclusion, such as the word "negligently" to describe how something was done. For example, in a negligence case in which a plaintiff was injured due to an unmarked ice hazard on a ski trail, highlight the facts that show the plaintiff could not have avoided his injury by being more careful: "The glare from the sun prevented him from seeing that the trail was covered in ice. As a result of the glare, he was unable to avoid the dangerous ice hazard." In describing the procedural history, state the date on which a lawsuit or criminal charges were initially filed, the legal basis for the lawsuit or charges and the relevant motions that have been filed in the case of a trial brief or the rulings by the trial court and previous appellate courts in the case of an appellate brief.

Present the legal questions. The "Questions Presented" section frames the issues for the court. It should identify the legal issues at stake, with sufficient reference to the facts of the case to make the matter concrete and compelling. Each question generally consists of one sentence, beginning with the words "whether" or "does". For example: "Does the public burning of an American flag during the course of a political demonstration constitute free speech subject to the protection of the First Amendment?" If you are preparing a trial brief, you may not need to include a "Questions Presented" section. Look to other similar briefs submitted to the same court and to the court rules to decide whether to include one.

Summarize your argument. The section called "Summary of Argument" should contain a clear and concise summary of what you will argue. This is basically a shorter version of your argument. Include only the most persuasive parts of your argument. Do not simply repeat the point headings from the table of contents. Follow the same structure you will use in your argument. Trial briefs often do not include this section.

Write out the full argument. The "Argument" section is the heart of the brief. This is where you will analyze the law that applies to your case and apply the legal principles to the facts. Each argument section or subsection should begin with an argumentative point heading. The heading should state in one sentence the main thrust of the argument to follow with enough detail and specificity for the court to understand the substance of the argument. If preparing an appellate brief, the point heading should always be capitalized and should emphasize why or why not the trial court decision should be overturned. For example: "THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN ADMITTING TONY'S STATEMENT BECAUSE IT WAS THE FRUIT OF AN ILLEGAL POLICE SEIZURE AND THEREFORE MUST BE SUPPRESSED UNDER THE WONG SUN DOCTRINE." If preparing a trial brief, a point heading does not usually need to be capitalized and should emphasize why the motion before the court should be either granted or denied. For example: "The court must not admit the prior trial testimony of the witnesses because even though the prior testimony exception to the hearsay rule may apply there are unusual circumstances that run contrary to the purpose of the confrontation clause." Beneath each heading, begin each section with a paragraph that summarizes the argument. Within the argument, you should make your strongest points and present your strongest authorities first. Support your statements with citations of the facts and to the law. When citing cases in support of your position, emphasize their similarities to your case. Anticipate what your opponent will argue and refute those arguments. For example, if you find a case that seems to support your opponent’s position, distinguish that case from your case. If you are responding to an opponent's brief, state your case before responding to your opponent's argument. Be as concise as possible without omitting necessary details. Judges are busy people and do not appreciate having to read long briefs when the same issues could have been covered more succinctly.

Proofread and edit. Read your brief out loud to make sure that there is no awkward phrasing or parts that do not make sense. Have someone else proofread the brief and recommend any edits that he or she feels are necessary.

Comments

0 comment