views

Pulwama: Surrounded by over a dozen students in a small room, Nusrat is busy, teaching students. Some kids chitchat while she is assigning homework to others. This room, in a single-storeyed residential house, is a temporary school for the children in the Newa, a locality in south Kashmir’s Pulwama district. The lockdown in the Kashmir Valley spills over to the third week since the Central government scrapped J&K’s special status by amending Article 370.

Nusrat (who doesn’t want her complete name to be used) is a college student in Pulwama. She also used to give tuitions to children from the neighborhood. The schools have remained shut since August 5. Hence, Nusrat has decided to open doors of her house for the kids in the vicinity. The modest house she and her family live in has turned into a temporary school.

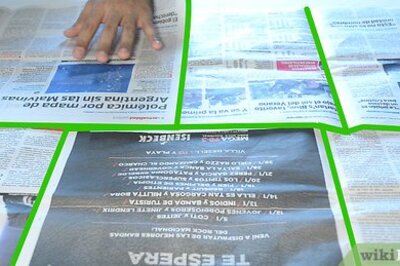

The space of the single room, where she teaches, is not enough. She has spread a tarpaulin sheet in the lawn of the house and some students sit there, waiting for their teacher. Seeing her taking initiative to teach the neighborhood kids, two neighbours decided to join in.

The road leading to Pulwama looks desolate. An occasional car whizzes past, as the students, carrying their school-bags walk towards Nusrat’s house. “We are coming here for the last two weeks. For now, this is our school,” Basit, a Class 4 student of Merry Land Public School, Newa, told News18.

Nusrat is also a little wary that her initiative to engage school kids in these trying times may engender trouble for her. “I am trying to help these kids not waste time. I don’t want them to stay away from books at this age. But this can also lead me to trouble,” she said, without elaborating further.

The students come early in the morning and Nusrat finishes her lessons by 11am. Since the lockdown, Nusrat is herself not able to go to college. Her studies have also been affected by the recent turn of events in the Valley.

Basit says he misses his school and the friends there. “There are three students in my class here. We are taught all the subjects here,” he said. But for him, nothing can replace school. “Here we have to sit on tarpaulin, finish our studies quickly and then leave for home. We don’t play. My friends are not here,” he says. But under these circumstances, it is better, he feels, to attend this community school than to sit at home.

“My parents don’t allow me to venture out of home. They are worried about the situation and I have to play alone every day in the lawn,” he says. Parents of most of the children accompany them in the morning to Nusrat’s place and come back at the time they are supposed to leave.

Last week, the government ordered re-opening of primary and middle schools in the Valley, but attendance has been thin, that too, at very few places. Since then, the government is reluctant to share details about the functioning of schools. News18 visited over a dozen, private and government, schools in Pulwama district but all were closed.

Nusrat and her friends (who don’t want to be named) are teaching these children voluntarily. “I want to do something for my tormented society. Looking at these kidsm

I feel very bad. They are living in terrible times” says Nusrat.

As the students are not able to go to school, people like Nusrat become a flicker of hope. “I am not able to teach them in a proper manner, but I don’t want them to cease taking education in these circumstances. Education should never stop,” she says.

But parting away with the prevailing state of affairs is not easy. The students, especially the younger ones, are disturbed. “My son, who is seven-year old, keeps me asking strange questions,” says Shazia Iqbal, mother of two, and a teacher who lives in a village in south Kashmir’s Anantnag. “The children are very tender. I don’t know how to answer their questions,” she says.

Iqbal is also teaching students of her locality and like her son, she finds other students disenchanted, always asking questions about what is happening around. “It is difficult to make these kids understand about the situation,” she says. Shazia is organising painting competitions and trying to involve the students in other activities to divert their attention. There are more people like Nusrat and Shazia, voluntarily teaching the students of their neighborhood amid the lockdown.

Community schools during extended hartals and protests are not new to Kashmir. This happened in the 2016 as well, after the killing of militant commander Burhan Wani, as Kashmir remained shut for months together.

Most of these schools, however, teach the students who are studying in lower and middle classes. For students of higher secondary schools and colleges however, there is no alternative. “Since the last three weeks, I haven’t been to college. There is no internet and no other way to study,” says Andleeba Shafi, a college student from the uptown area of Srinagar.

Rahil Hameed, a student from Anantnag, was studying at a coaching centre in Parraypora locality of Srinagar for medical exams. On August 3, the coaching classes were suspended for an indefinite period and Hameed rushed to his home, without knowing how long he will have to stay at home. It has been 22 days since and he is worried about his future. “All of my books are in my hostel. I am wasting crucial time. It is like our future is getting destroyed,” says Hameed, who is angry and feels helpless.

Comments

0 comment