views

History might be many things—sublime, ridiculous, tragic, predestined—but it is also an agglomeration of the bizarre and the surreal. The story of how Warren Hastings, one of the most prolific and ruthless looters of India, was humbled to the extent of seeking a certificate of good conduct from a group of Sanskrit pandits in Varanasi is a prime example of the surreal and bizarre. This story, long forgotten and buried, deserves retelling—especially today, when “Great” Britain finds itself irrelevant and marginalised in the global order, an order it shaped and controlled just a century ago.

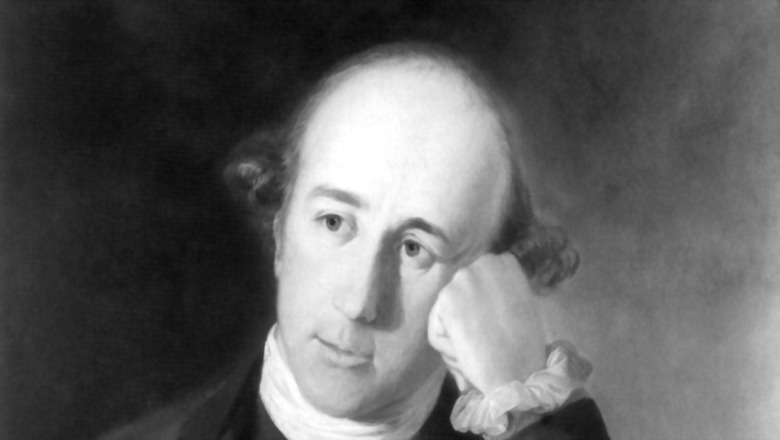

The prolonged impeachment trial of Warren Hastings culminated in his acquittal on 23 April 1795. The acquittal itself was a secondary outcome, as the trial had irreparably tarnished his reputation, not just in England but across the world. The voluminous records of his impeachment proceedings remain a lasting monument to his well-earned infamy.

These proceedings offer abundant evidence of Hastings’ utter lack of scruple or character. This was the gold standard plunderer standing trial for a career spent looting India. And even while he repeatedly took the stand in court, he had opened up a parallel track to save his skin: seeking endorsement from the very people he had oppressed and plundered.

Hastings typically lacked the courage to seek their endorsement directly. Instead, he unleashed one of his many sleazy minions to execute this deed – a man named Charles Wilkins, who had studied Sanskrit in Varanasi under the tutelage of Pandit Kalinatha. Incidentally, Wilkins holds the distinction of producing the first English translation of the Bhagavad Gita.

Even as the impeachment trial raged on, Warren Hastings clearly realised he was on the losing side and needed to gather support from all quarters—be it the King of England, the corrupt aristocracy, or his personal network of plunderers and pirates in the East India Company. He had fattened them all by distributing a part of his pillage of India.

The other category of people he sought support from were the unfortunate victims of his loot. Remarking on this phenomenon, the prolific Sanskrit scholar P.K. Gode writes: “In the history of mankind, occasions when a Viceroy needs a testimonial from his humble subjects, are few and far between. Rarer still are the occasions when such testimonials find a place in official archives or private publications.” (Emphasis added)

These official archives are formally titled, Debates of the House of Lords on the Evidence Delivered in the Trial of Warren Hastings, Esquire, published in 1797. The specific section in which Hastings begs for support is titled Proceedings of the East India Company in Consequence of an Acquittal: and Testimonials of the British and Native Inhabitants of India, Relative to his Character and Conduct while he was Governor General of Fort William, in Bengal.

When the news of Hastings’ acquittal became public, a deluge of congratulatory letters reached him from various quarters. The full correspondence relating to this event is preserved in the aforementioned documents.

Among these, three letters are relevant in this context. One letter was in Persian and two in Sanskrit. Interestingly, these letters were sent to Hastings via a covering letter dated 19 December 1796, by the Secretary to the Government of Bengal. The aforementioned Charles Wilkins, described therein as an “ingenious friend of Mr. Hastings,” translated the Sanskrit letters to English. We can briefly examine the contents of the two Sanskrit letters.

The first letter which endorsed Hastings’ good conduct ends as follows: “This writing is dated the 7th of the light fortnight of the moon of Phalgoona in the year 1852 of the Samvat.” It was stamped with the seals and signatures of a whopping 43 Sanskrit pandits of Benares.

The second letter was more revealing and reads as follows: “We, a number of your industrious Servants, Brahmanas, and other Hindus, Yavanas (Musalmans) and other foreigners, whose constant residence is here on the delightful, beautiful, and forever, full-flowing stream of the sacred Ganga; where, by conquering sundry evils, we have become pure, and where we enjoy at ease abundant happiness flowing from the profits derived from our several exertions, humbly address you, the illustrious Nawab Amaduddowla, Governor Hastings Bahadur Jaladat Jang.”

This second letter was originally intended to be used in a signature campaign. It was circulated among all prominent citizens of Benares including Hindus, Muslims and “other foreigners” in the city. However, the Muslims refused to sign this letter because it was drafted in a ‘kafir’ language. And so, they put out their own version lauding Hastings in Farsi. This was the third letter, mentioned above. It was eventually signed only by Hindus. Some of the Hindu signatories came up with creative passages extolling Hastings.

Here is one sample written in Sanskrit by Srinivasa Pathak. “May the good wishes, abundantly offered up by Srinivasa Pathak, the son of the astrologer Paramananda, bless Hastings… By the pleasure of Visvanatha, may treasures of good wishes be the prize of victory to Hastings, Sovereign of the land of truth!” The total number of signatories was 167.

To cite P.K. Gode again: “These names are very important to the students of history in general, and of the history of the city of Benares in particular.” Among other things, both letters clearly reveal a common theme: the unbroken continuity of Kashi as the unparalleled hub where pandits, sadhus and sages from all parts of Bharatavarsha met, interacted and exchanged ideas and philosophy.

The surnames and titles of the pandits mentioned in both lists unambiguously reveal the identity of their native provinces. Unlike in our current period of hardened linguistic and regional identities, the pandits of that era lived as one, bound by Sanatana Dharma, Sanskrit and Samskara, whose most radiant centre was Kashi.

But there is a more significant facet to these letters written by devout Sanskrit pandits addressed to a colonial plunderer like Warren Hastings who had uprooted their culture and looted their sacred country. It raises two vital questions: why would they even write such a letter to him? Was their effusive praise for Warren Hastings rooted in genuine admiration for him?

Once again, P. K. Gode answers it with his characteristic candour: “How far the addresses presented to Warren Hastings are a genuine expression of the feelings of their signatories I am unable to say because in such types of addresses, the hand of the officialdom is often at work, suppressing the likes and dislikes of the people, whose voice they are supposed to represent.”

In this light, there is every reason to conclude that these letters were written under duress. In the end, Warren Hastings escaped unpunished, and his whole impeachment trial only reaffirms an ancient truth that the bigger the criminal, the greater the chances of his acquittal.

The author is the founder and chief editor, The Dharma Dispatch. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment