views

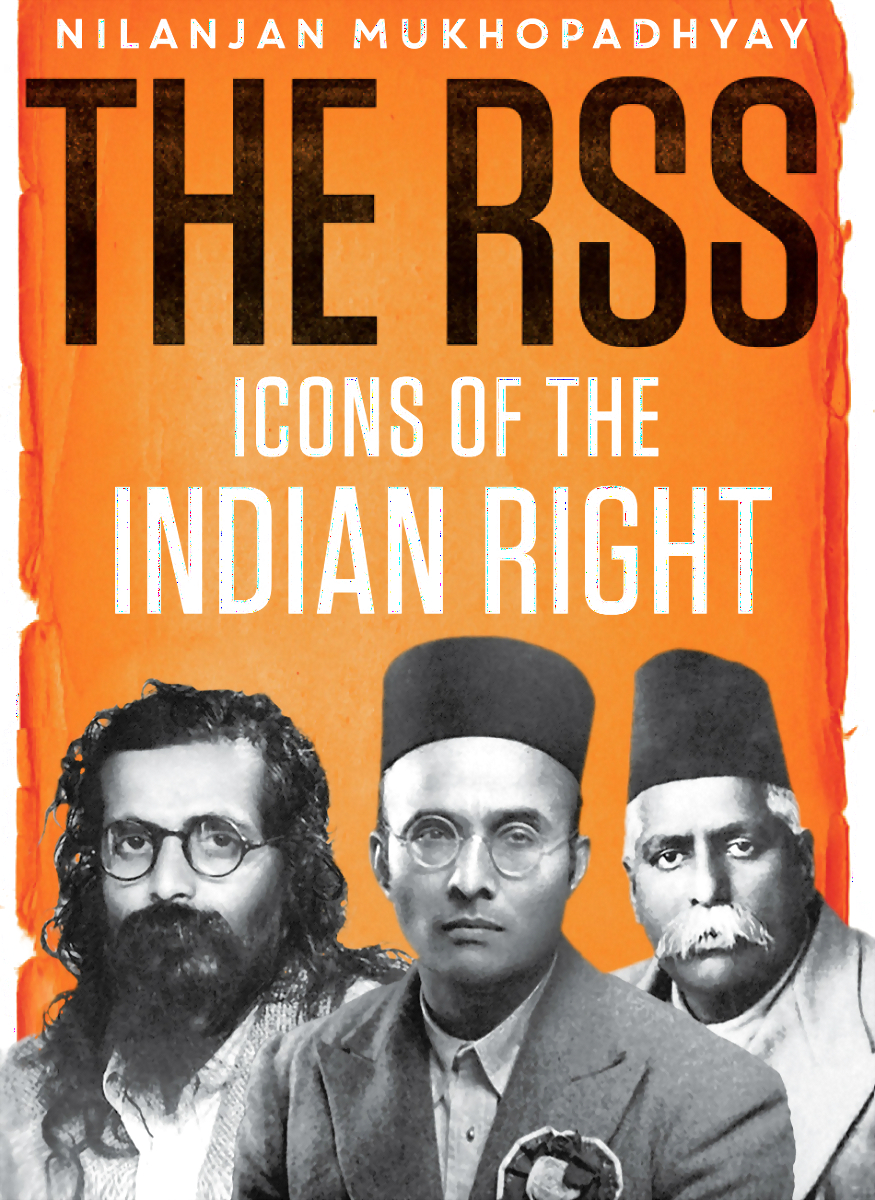

New Delhi: Several attempts have been made by researchers and authors to decipher, decode and demystify the equation of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) with politics, and its participation (or non-participation) in India’s freedom struggle. In his latest book, titled ‘The RSS: The Icons of the Right’, Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay has brought out significant chapters from the RSS history, where freedom struggle and electoral politics were widely discussed and acted upon.

At the helm of this contemplation were two men within the hierarchy of the Sangh. One was second sarsanghchalak MS Golwalkar and the other was his successor, Madhukar Dattatraya Deoras, also known as Balasaheb Deaoras (who could be have been the second sarsanghchalak but had to wait for 30 years to ascend the title).

The book covers all icons of the RSS, putting in perspective the veneration of Sangh leaders by the current dispensation, and also focuses on its political aspirations.

Certain chapters in the book give a thorough understanding of Sangh’s present activities -- why it started an online campaign to highlight its role in the freedom struggle and why its participation in Emergency under the third sarsanghchalak is considered a ‘second freedom struggle’ (as mentioned by Pralay Kanungo in his book, ‘RSS's Tryst with Politics’).

The dispatches on Freedom Struggle

Mukhopdhyay has shared conversations between KB Hedgewar, MS Golwalkar and Balasaheb Deoras that make you question how different the dynamics of the organisation could have been today, had Deoras succeeded Hedgewar?’ Would the RSS, which publishes its own works on participation in the freedom struggle, would have then told a different story?

The author believes that things would certainly have been different as Deoras believed in full participation in politics, while Golwalkar and Hedgewar were unrelenting in keeping the RSS out of mainstream politics.

In 1945-46, when Golwalkar was the sarsanghchalak, Deoras was determined to make RSS move ahead lest it becomes “a sect and lose its relevance to the upliftment and building of society. It will become a ritual.”

During the Quit India Movement in 1942, Deoras approached Golwalkar and expressed his interest in joining Mahatma Gandhi’s movement. He appealed, “In 1931, Hedgewar participated in the Jungle Satyagraha after leaving Paranjape in charge of the Sangh. You have declared me to be the actual sarsanghchalak and call yourself a mere proxy holder. Since you are already at the helm of affairs, allow me to join the Quit India Movement, while you remain in charge of RSS.”

But Golwalkar stuck to this resolve of keeping the RSS apolitical.

The RSS’s finest hour under Golwalkar’s leadership was in 1946 when “Jinnah’s Direct Action gave the Sangh the opportunity of the lifetime. Rather than joining hands with Gandhi and nationalist forces to defeat the participation designs, the RSS came into action to finally prove, through proactive as well as retaliatory actions, that Hindus and Muslims could not live together.”

Deoras’ obstinacy for political participation surfaced at the time of the first sarsaghchalak as well. He had raised the issue of political participation during Hedgewar’s time in the 1930s.

At the time of Civil Disobedience movement, Deoras was quoted as saying, “When questions were raised about how the daily shakhas would fulfil the dream of liberating the Hindu Rashtra… we would disagree with doctor ji and expressed our doubts.”

But Deoras was not able to turn his opinions into actions as Hedgewar encouraged only individual participation. In 1930, Dandi March and Salt Satyagraha shook the foundations of the British Raj and Hedgewar told his cadre that Sangh has not resolved to participate in this movement. “However those who would like to participate in their personal capacity are free to do so after obtaining permission from the Sarsanghchalak.”

Throughout the decade Hedgewar’s focus was “centered on strengthening the Hindus against Muslims.” Political participation mad e the earlier sarsanghchalaks clash on several occasions. The political ambitions were later pursued during Deoras’ tenure as the sarsanghchalak.

Political Plunge

Mukhopdhyay has penned down the incidents from Deoras’ political life which throw light on the tumultuous phases he went through in attempting to take RSS closer to power than what his predecessors “could have ever imagined.” He anchored the Sangh in such a way that it was acknowledged “as a force which was capable of influencing electoral politics, mainly because of a proactive sarsanghchalak who was even then preparing for the next round.”

In 1962, he assisted Jana Sangh during the general election campaign. Against the conventional wisdom of the outfit, Deoras in 1963 put RSS thinker Deendayal Upadhyaya as the Jana Sangh candidate for the by-election in Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh.

Deoras gave preference to Upadhyaya over the dedicated soldier Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and by 1967, started collecting accolades for his political decisions. He was appreciated for his “far-sightedness” in appointing Upadhyaya as the president of Jana Sangh as the outfit gave its best political result under his leadership. It won 35 out of the 520 parliamentary seats in Lok Sabha, and more than 250 seats in state assemblies.

Later in 1971, when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi garnered majority of votes, there was discontent simmering against her government on grounds of corruption. Deoras sensed a great opportunity in this sentiment against the Indira government and sent out instructions to the Jana Sangh leaders to utilise the sentiment to win the sympathy of the masses.

The author has, in fact, mentioned this as one of Deoras’ biggest achievements. Deoras, he writes, will be best remembered for the “agitation launched against the misdemeanors of Indira Gandhi government, which led her among other reasons to impose the Emergency in June 1975”,

Mukhopdhyay also credits him for “bringing to power the first non-Congress government at the Centre and thereby catapulting the Sangh parivar to the mainstream,” and for making the Ram Janambhoomi agitation the kernel of India's Right-wing politics in the 21st century.

Aware of the influence he had over India’s political leadership, Deoras reveled in the power he exerted, but his journey was not without challenges.

Comments

0 comment