views

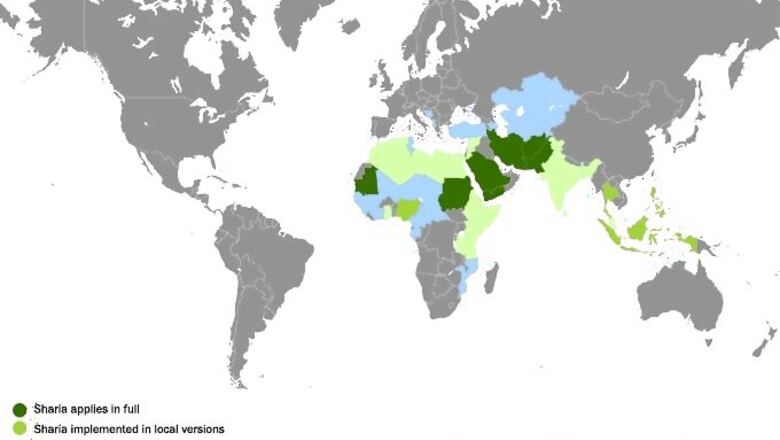

After years of creeping fundamentalism, Brunei's Sultan has decided to say it like it is: the country has opted for the Islamic sharia legal code in full. At a time when the Uniform Civil Code is in the news here, Brunei's decision has little immediate impact considering the limited application of sharia throughout the Islamic world.

The worrying factor for countries with significant Islamic minorities including India, Sri Lanka and the West, however, is the increasing radicalisation that tipped the balance in Brunei. On the other hand, large parts of the Islamic world which have opted not to have sharia at all, like European or Central Asian Islamic majority states, have also not seen radicalisation.

On the face of it, Brunei is not a significant power: its twin claims to fame being the one barrel of crude oil it produces for every four of its citizens every day, and a Sultan known for his very conspicuous consumption, gold-plated bathrooms, car collections, the works. Despite the kind of lifestyle that would leave radical Islamists apoplectic, or perhaps because of it, the aging sultan had been displaying signs of Islamisation for some time.

Amid the widespread condemnation, including by the United Nations, of what is seen as adoption of a system that promotes torture, legalised cruelty and misogyny, this development needs to be looked at in the context of the wider Islamic world. The good news for everyone else is Brunei is a rather isolated instance, and a strange one. Its EMI method of sharia implementation means Islamic laws will be gradually introduced, with the more violent criminal codes coming into effect after a year.

There are only a few Islamic countries in the world where sharia is implemented totally and exclusively. These include the obvious examples, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran. Like Brunei, these are absolute monarchies or theocracies.

Brunei therefore will have a far easier time implementing sharia in toto than most other countries can today.

Afghanistan and Pakistan, the other two in this list, have struggled as democracies and been subsumed by Islamic radicalisation over time. Pakistan's Federal Shariat Court (FSC) model, for instance, has supremacy over High Courts and lower courts, remnants of the British legal system. Even the Pakistan Supreme Court, the only court of appeal against the FSC, is bound by judgments which determine whether a law is Islamic or not. Like Pakistan, Mauretania on the northwestern African coast opted for sharia in the early 1980s, not without considerable opposition from its black and women citizens, who feared victimisation, with good reason as it turned out afterwards.

The other country which opted for sharia very recently and which bears mention is Sudan. After its southern Christian region went its separate way, Sudan introduced sharia in 2011, and still hasn't made up its mind about when to implement it. Sudan's legal system has been heavily condemned for instances where women have received extreme penalties such as stoning for charges of adultery, on what would be termed very flimsy evidence by secular courts.

Most of the rest of the Islamic world does not have sharia at all, including Turkey, European Muslim-majority countries like Albania and Bosnia & Herzegovina. In Central Asia, Azerbaijan and the Russian-influenced Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Tajiks and their neighbours have chosen not to let sharia have a say in their justice system in any form. Their fellow members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) from central Africa and the Maghreb, including Tunisia, Mali, Niger, Chad and Mozambique also do not have sharia laws either in the criminal or civil justice systems.

India and Sri Lanka, however, are among those Islamic minority countries which occupy the middle ground between these two groups, with sharia laws in effect for civil but not criminal matters. Islamic countries in this group include Algeria, Egypt, Morocco and Libya. A case may be made that such partial application of sharia is one of the reasons radical groups seek greater Islamisation, in their effort to get sharia in all spheres.

A prime example of this is Egypt, whose Islamic Brotherhood has for nearly a century wanted a return to full sharia and rejection of modern western legal systems. On the other hand Tunisia, virtually next door, doesn't have sharia at all, and is also considerably less radicalised (although its institutions are under pressure after the Arab Spring). Neither are the Kazakhs, Azeris or Uzbeks. Experts see a direct co-relation between the existence of partial sharia and the possibility of further radicalisation in Islamic societies.

The bad news arising from Brunei's decision is exactly this rising tendency to opt for full sharia and reject modern secular courts, which emphasise due process, equal treatment of women and humane prison terms or punishments. Brunei, as observers believe, must have been influenced by the Malaysia experience of the past two decades.

The sultanate, after all, does fall wholly within the Malaysian province of Sarawak on Borneo island and is mainly Malay in ethnicity. Malaysia has full sharia in a few provinces and partially elsewhere, but with rising Islamisation secular legal systems are beginning to buckle under the pressure, as are administrative and political structures.

Neighbour Indonesia, which has full sharia only in the region of Aceh, is also experiencing internal turmoil regarding Islamic laws versus a legal system inherited from its former Dutch colonial masters. Brunei's decision will only be a shot in the arm for radicals in the neighbourhood, and cause for worry for liberal Malaysians and Indonesians, as well as watchers of the larger Islamic world, as yet another Islamic country chooses what can be termed an anachronistic legal system.

Comments

0 comment